Aug '08 - Jun '10

It's been 10 days since my last post--so much happens so fast, I feel like I have five unwritten posts and they keep stacking up. Tokyo continues to impress me with its soft contours, but I should add that there exists a shrill, sonic violence inside of it. For one, there are these ultra high frequency speakers (probably up around 20kHz) situated around entrances to car garages. The decibel level was such that it clipped my microphones recording normal street noise. I have to run past these things when I encounter them. I guess they are to keep pigeons or something from wandering down in there? Or maybe to make children who can hear such high frequencies more alert to exiting cars. Or is this "violence" a soft thing too, projected at a distance and without hands?

Sumimasen.

Another sort of sonic violence occurs around the military bases. Naval Air Station Atsugi is one such exhibit. I spent a day circumambulating the base, and counted at least 20 loud jet take-offs over a four hour period…not to mention the constant din of choppers coming and going. It is like an international airport that the locals are prohibited from using. Japanese Self-Defense Forces also use the airstrip, but the loudest jets belong to a US aircraft carrier docked at Yokosuka in the bay. They will be moving to Iwakuni near Hiroshima in the next few years, pending the approval of (Japanese funded) construction of facilities down there. Simply put, it is costing the Japanese government too much money in payouts to the locals who have repeatedly protested the noise.

You will not forget the sound that the carrier wing makes. My first experience was about 9:30 in the morning in a neighborhood adjacent to the base. People were about putting recycling in bags tethered to the barbed wire fence. Someone was sweeping a porch with a straw broom. Out of nowhere, the sky was ripped open by a tremendous roar. I looked up to all corners of the quaking blue sky, expecting to see fissures of black and metallic dust from the sky shaking apart. At least I expected to see the machine that could produce this volume of sound. With sonic shrapnel raining down from an invisible jet engine caldera, I saw only the empty blue sky.

To my greater astonishment, the neighbors continued to go about their business as if deaf. They didn't even look up. Not a flinch in their routine. So this is what it is like to live next to a foreign military base. I am looking for ways, other than in writing, to describe the strange juxtapositions of civilian and military.

The soldier's obscene gaze, on his surroundings and on the world, his art of hiding from sight in order to see, is not just an ominous voyeurism but from the first imposes a long-term patterning on the chaos of vision, one which prefigures the synoptic machinations of architecture and the cinema screen. In the act of focusing, with its proper angles, blind spots and exposure times, the line of sight already heralds the perspective vanishing line of the easel painter who, as in the case of Durer or Leonardo, might also be a military engineer or an expert in siege warfare.

Paul Virilio, War and Cinema, p. 49

How to draw what you cannot see? Also: how to draw what you should not draw? The problem has chased me ever since I began this fellowship, studying spaces which are not only difficult to access, but usually sign posted as forbidden to "produce maps, make sketches, drawings, recordings,etc." Much can be gleaned from web searching, walking the edges of the base, and looking at aerials. My subject of military space is not so secret. There are spaces that I have been able to access, now having toured two bases in the Tokyo area. I have, in fact, too much information. Is this not the predicament of our age?

But the local problem of how to represent the things I am seeing/hearing remains for me and it has everything to do with architectural convention. I have avoided such things as cross-sections and plans, assuming that the code of what is military space in the 21st century, a thing with no front lines, something atmospheric, demands a new form of representation. I have faithfully recorded sound with absolutely no idea what I am going to do with it. I have come to an impasse, an information overload and the release valve is jammed. Traveling compounds the lack of outlet, for I can't justify shutting myself out from Tokyo for a week just so I can draw.

Back in thesis prep, I looked at Mary-Anne Ray's Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings, published as Pamphlet Architecture 20. In describing a well which spirals down upon itself, a remarkable transition from the outside world, she could almost be talking about a military base:

…a kind of 'flip-flop' occurs between the architecture of this inevitability in response to a hard and fast program, and space which has embedded in it extreme abstraction, deep perceptual shifts, and multiple and strange positions for the travelers who now occupy it.

Her drawings are still evocative because they are stretching architectural conventions. Unrolled elevations, sections, and axons--the amalgam of which conveys in a somewhat legible manner (I think you probably need to go there to really understand the drawings) the layered spaces and difficulty of perceiving them.

Trevor Paglen has through several installations attempted to map and document the 'Black World'. I am a fan of his work, though I was disappointed by the last thing I saw of his, a giant globe of the Earth with figurative spotlights dancing across it, representing the watchful eyes of 189 spy satellites floating above our heads. The representation evoked mystery and conflated star constellations with man-made satellites, but it was made without the signs of its making. Apparently data was compiled from amateur observers. To be fair, how would you accurately map those satellites? Still, I would rather see the failed attempts at mapping than a polished, special-effects installation.

The void is an evocative theme. It works two ways, across a threshold. For the military, what lies outside the fence is, as far as I have seen, always represented on their maps as a blank region. And in city plans, the military base is a grey block, a chess piece which makes no move and can never be taken. There is an important difference with each type of "void space" here. From within the base, the world outside is an ocean, an expanse of otherness which laps at its shores but has no real effect there. From without, the military space is dense, solid, filled in. It may as well be a wall projected a thousand feet high. The military can virtually come and go as it pleases, but civilians must be screened, and only a select few--those who work there--have access.

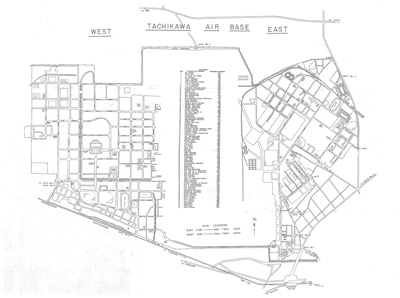

I was recently at the public library in Tachikawa City, west of Tokyo, and came across an old map from 1930. The Japanese military had recently bought up farmland, and in so doing, erased that part of land from the map:

After the war, the Americans moved in and occupied the base. Here is what their plan looks like (the shape of the base having changed):

The more I look at maps, the more I need to understand the dimension of that edge line-- how is it negotiated, violated, amplified?

There are nuances to the edges of military space. Intersections occur: bird feeders in the barbed wire, tunnels under the bases, military bridges over civilian roads. The metaphor of the island and the solid wall do not hold up. This is the essence of my investigation: studying these exchanges, and discovering the fissures--through drawing sections and mapping--which may lead to new tools of representation.

5 Comments

I was wondering if you had any idea how you were going to use the sonicscrapings you have bene making. Maybe you should make part of your thesis project into some sort of sound installation?

nam, good idea--the sound will help tell the story, to be sure. it provides the 4th dimension.

if I could represent in sound what Mary-Ann Ray describes as "deep perceptual shifts", I think I could be on the right track.

wouldn't the sound be the force behind generatign the "deep perceptual shifts" as opposed to the representation of those shifts...?

Nick,

"To my greater astonishment, the neighbors continued to go about their business as if deaf. They didn't even look up. Not a flinch in their routine."

That interests me. How do we learn to live with a freeway in our front yard or a toxic dump in our backyard? Or in your thesis, how does a Japanese or Korean or German learn to find "peace" with an American war base next door? Or do they really? I guess that is what you are studying.

Love your writing,

Brian

Brian welcome to archinect! Yes I think that is a potential thesis question. How is it that American bases in foreign countries have become a 'situation normal'? At the bottom of this, one has to ask what is normal?

Bases themselves are so bland, so "ordinary" in appearance themselves.

They seek monotony in their context. Yet like a soldier walking the streets in a crisply ironed uniform, against a crowd of 'normal' civilians, the soldier is the very definition of foreign and exotic.

Nam: good point. I am a little skeptical of my own post-processing of sound, as if I am trying to warp the sound into a representation of my total experience.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.