Hi Archinect!

Hi Archinect!

I'm at MIT today for Margaret Livingstone's lecture on visual perception. She'll be talking about how works of visual art can inform us about how we see. (Her excellent book with many visual games and informative optical illusions is called Vision and Art: the biology of seeing.)

12:37: Vision is information processing, and visual computations are SIMPLE, LOCAL, and OPPONENT (with one neuron often inhibiting its neighbor).

Center-surround cells: they are activated at borders, turning a contour into a line drawing.

Example: what color are the lines in this drawing? Black. What color is the projector screen? White. It's the same light being transmitted to our retinas; our tonal judgment is a relative distinction.

Comparison of a painting and photograph of Livingstone's son, doing the same thing with a candle. A photograph captures a rapid (exponential?) drop-off of light through distance, but our experience is more like the painting, because our center-surround cells help us process the image differently.

Comparison of a painting and photograph of Livingstone's son, doing the same thing with a candle. A photograph captures a rapid (exponential?) drop-off of light through distance, but our experience is more like the painting, because our center-surround cells help us process the image differently.

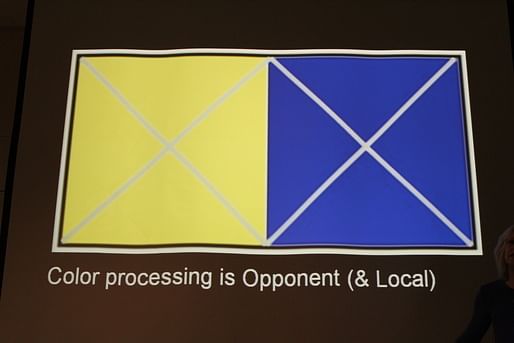

Monet paints blue shadows; this draws on the notion of opponent information processing (i.e. yellow and blue are contrasting shades).

Ray-tracing software programs aren't helpful; our low-level visual processing systems don't care about the physics of light in this way. "You don't ping things and somehow determine how far things away are according to some sonar system. You see the world as vividly three dimensional according to two flat retinal distances." To do this, we use:

We can gain perspective cues from shading patterns that are "locally plausible but globally impossible" (i.e. mutually contradictory).

12:49: "Colors are only symbols. Reality is to be found in luminance alone." Pablo Picasso.

Color and luminance do different things for us in vision.

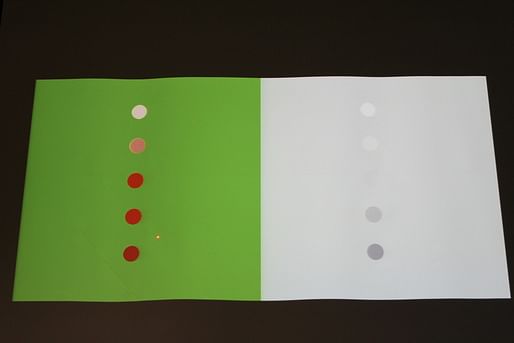

We have three cone types in our eyes; we get luminance by summing the three. Example diagram of color contrast without luminance contrast. Monet's paintings play with this, making forms almost "wiggle" on the painting, like the red sun on the gray background.

The parts of the brain that are responsible for different functions are determined by studying people with localized brain damage.

The "What" system is our basic mammalian visual system. The older "Where" system (or perhaps more accurately called the "How" system) has to do with the location of things in space. Spatial organization and object identity are separable: note drawings of bicycles, a cross, and a clock by people with damage to their "Where" system.

Depth perception is aided by luminance contrast. Depth perception is blind to color; it doesn't matter for depth perception what color shadows are, as long as they're an appropriate luminance.

1:09: Mona Lisa's smile is a bit blurry, and our visual acuity is sensitive to location. Our peripheral vision is better at seeing big, blurry things; our central vision is better at details.

1:15: Humans are better than any computer algorithm at facial recognition.

We have special "face cells" that each pay attention to two or three characteristics about a face.A cell will respond to really large inter-eye distances, and another will respond to really low inter-eye distances (and each is inhibited by the other condition). Face processing primarily looks at differences from the average (like a caricature). "Opponency is local" because inhibitory neurons don't extend very far; excitatory neurons extend farther.

1:24: The nature of vision as information processing is reflected in children's drawings. Very young children draw people as faces on legs, because this is what is relevant to them.

You can get very specialized agnosias (which indicates that we have dedicated parts of our temporal lobes for each of these categories.)

When a face is upside down, we process it differently; hence, the manipulated drawing of Angelina Jolie (on the left) looks a little weird upside down, but when these images are right side up...

[scroll down...wait for it]

YARRRRRRGHHH

1:30: Stereo matching:

Klimpt couldn't see stereopsis, since he was cross-eyed; does this inform how he used depth perception in his paintings?

Dyslexics often complain that black and white text jumps around on the page. It turns out that for people with dyslexia, the the timing of the Where and What systems are closer together (usually the Where system is faster). Dyslexics are over-represented in populations of artists, music, and computer programming; dyslexics tend to see the world in a flatter manner.

Livingstone has studied this quantitatively, but here she's highlighting just a few famous artists: Chuck Close, Dag Hammarskjold, etc. 3% of the population has significantly misaligned eyes (strabismus). You can determine this very easily by looking at the light reflecting off of the eyes in a photograph; if the light reflects off of different parts of the pupil, then the eyes are misaligned. People with misaligned eyes are highly overrepresented among artists. (In paintings, the eye on the left tends to be the one that deviates outward, and in etchings, which are produced by flipping the image left-to-right it is the right eye.)

Babe Ruth was almost blind in one eye.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

2 Comments

Interesting. The more I find out about this type of stuff the more I'm in awe at how much we take for granted visually, thanks for live blogging it.

For Dyslexics, Christian Boer has designed a typeface that makes it easier to read. Check out the video ... http://youtu.be/VLtYFcHx7ec

Hey thanks, Brian! Yeah, me too. It is amazing how much our cultural practices and technology (e.g. photography) affect how we understand our own experiences (e.g. thinking that we see like a camera sees).

Thanks for the video--I'm looking forward to checking it out!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.