Hi Archinect!

The full title of Mauricio's talk is "NYPL Labs Building Inspector: Extracting Data from Historic Maps."

From the OpenVis Conf website:

Mauricio enjoys playing with code, objects and all things interactive. He is currently an interaction designer at NYPL Labs, The New York Public Library’s digital innovation unit.

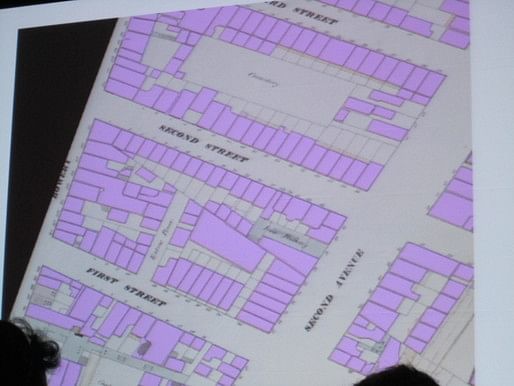

The New York Public Library map collection contains hundreds of atlases and maps spanning several centuries. Among them are US insurance atlases from the 19th and early 20th centuries. These atlases offer a wealth of geographic information about buildings in New York City such as addresses, building materials, height and use. However, this data is currently 'trapped' in these atlases, unavailable for public research outside of the NYPL map room.

The Building Inspector is the latest tool by NYPL Labs to extract data from these atlases through a combination of computational (vectorization, computer vision, alpha shapes) and human (crowdsourcing, game design concepts) processes.

This session will describe the workflow & computational methods behind the Building Inspector and provide additional information on uses of this data as well as the implications of open access to historical data.

It's a lot of work to manually extract data from printed historical maps.

It's a lot of work to manually extract data from printed historical maps.

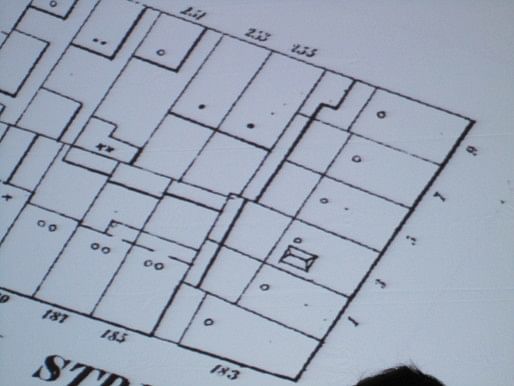

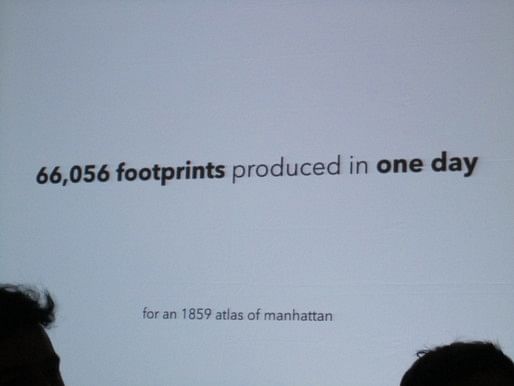

Digitizing the maps is a first step, to allow people not located in NYC to have access to the maps. The second step is "geo-rectification," or making the maps match Open Street Map. About 120,000 building footprints were produced in three years by staff and volunteers--but that covered just one historical year of maps. Asking around, they eventually found someone--Mike Resig, the brother of John Resig who also presented this morning, in fact--who worked to develop an automated way to develop the maps.

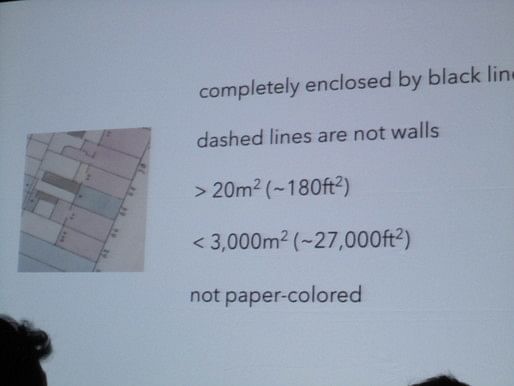

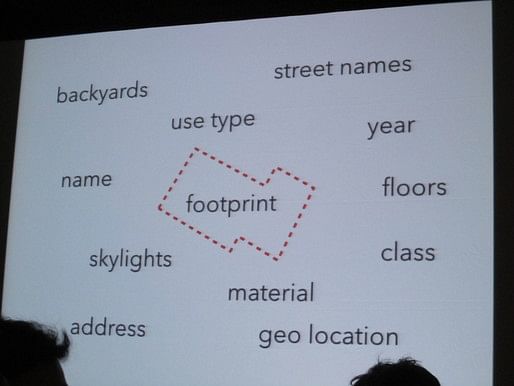

What is a building, in these maps? It has these qualities:

But the maps aren't perfect, with gaps, artifacts, and wear and tear on the paper.  First, they made the map black and white.

First, they made the map black and white.

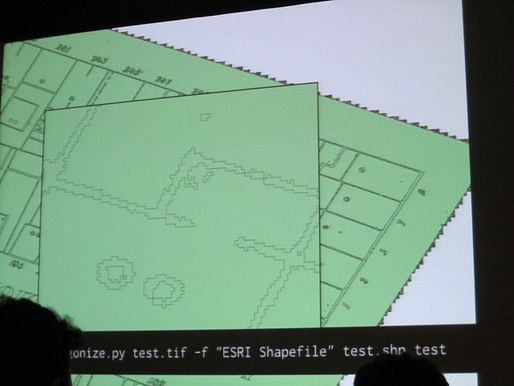

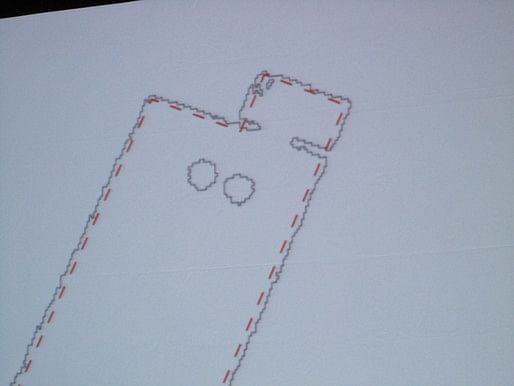

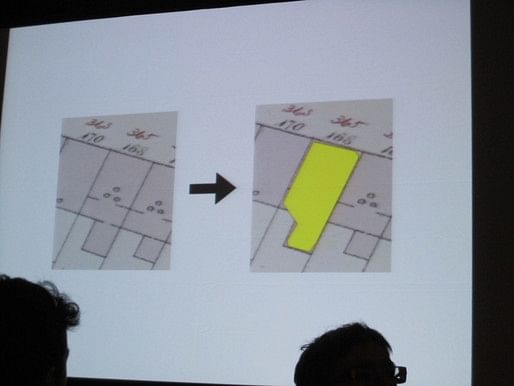

Then they used a Python script to interpret the lines as polygons, and then they simplified these polygons. They then use a set of methods (brute force) to create a set of points that describe the outline of the building.

Then they used a Python script to interpret the lines as polygons, and then they simplified these polygons. They then use a set of methods (brute force) to create a set of points that describe the outline of the building.

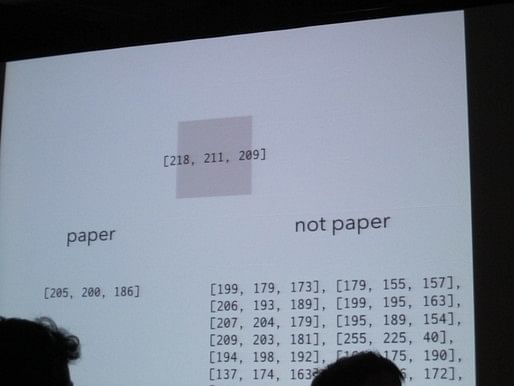

Once this is done, they sample the color within each building, find the average color and compare it to the color of paper in order to determine where there is shading.

This results in a set of polygons, which has errors but which is fast and accurate enough more often than not.

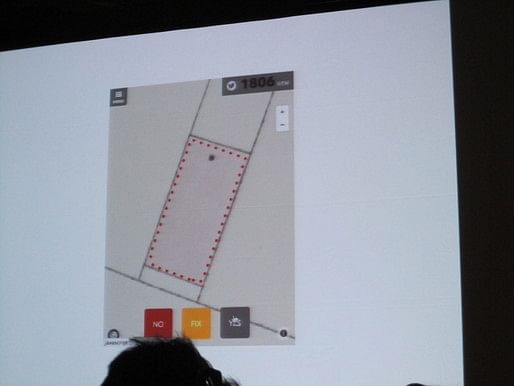

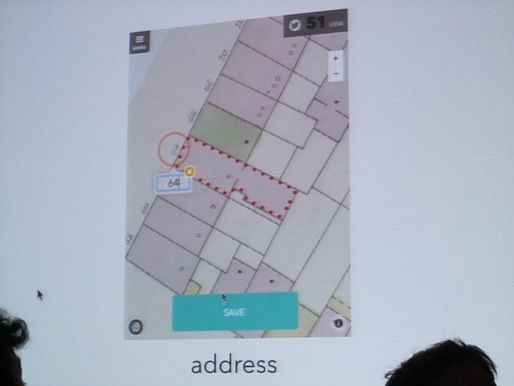

To verify they data, the work is then crowdsourced, and each footprint is validated by multiple inspectors--and this was the point where many of us heard of the project. The  building inspection can be done on the web or on a smartphone with a simple 'YES,' 'NO,' 'FIX' choices. There's even a button that lets you tweet how many buildings you've checked, and people will sometimes check tens or hundreds of thousands of buildings.

building inspection can be done on the web or on a smartphone with a simple 'YES,' 'NO,' 'FIX' choices. There's even a button that lets you tweet how many buildings you've checked, and people will sometimes check tens or hundreds of thousands of buildings.

Based on the success of this work, New York Public Library is now thinking about what else they can work on. They decided to crowdsource fixing the footprints and reading addresses, as classifying the color.

The resulting data is freely available, as is the source code. There's also a great summary of the project online at the Building Inspector NYPL website.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.