Hi Archinect!

Co-live-blogging tonight with Drew Harry from MIT Media Lab. Full house in (half) Piper!

From the GSD website:

Mohsen Mostafavi, architect and educator, is the dean and the Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design at the Harvard GSD. His work focuses on modes and processes of urbanization and on the interface between technology and aesthetics. He curated the exhibition "Nicholas Hawksmoor; Methodical Imaginings" at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. In the Life of Cities (2012) andInstigations (2012) are among his most recent publications. Nicholas Negroponte, a member of the MIT faculty since 1966, is a pioneer in computer-aided design. He is a co-founder of the Media Lab, opened in 1985, and founder and chairman of the One Laptop per Child, a non-profit association that distributes technology to children around the world. In the private sector, he has helped provide start-up funds to more than 40 companies, including Wired magazine. His book Being Digital (1995), has been translated into more than 40 languages.

[Note: If you're interested in these topics, please also see the related conference at MIT, Nov 21-21, 2013, called FUTURES PAST: Design and the Machine, organized by a great team of students together with Nicholas Negroponte, George Stiny, and Terry Knight.]

6:35pm: Dean Mohsen Mostafavi takes the podium. MM: “Today, people constantly use the word “visionary” and “pioneer.” In academia, people ask you about “vision” multiple times a day. But it’s apt to use the word “visionary” in the case of Nicholas Negroponte, as someone who has had transformative ideas and projects, in terms of architecture, computers, and the interface with humans--pioneering the relation between computers and architecture but always inserting the human.”

MM: His book, The Architecture Machine, had a tiny subtitle, Towards a More Human Environment, was published soon after he graduated. Each and every computer was becoming a part of you, becoming a part of you body.

[It is a VERY tiny subtitle.]

In the follow-up book, the Soft Architecture Machine, argues for the importance of understanding the makings of intelligence and the making of architecture, and the value of this understanding. Without this, the future of architecture could become very gloomy. Computers could add responsiveness. The possibility for a human to live in a build environment that is responsive to their needs. As against the idea of using computers to serve, Negroponte was interested in the singular goal of making the built environment responsive to me and to you as individuals, a right as important as the right to good education.

Has this promise been fulfilled? Can we speak of this close interaction between computers, humans, and the environment? Of course it is important that Nicholas went on in the 1980s to become one of the founders of the MIT Media Lab. Then in the most recent ten years, there has been some shift in focus from the relationship of architecture, computers, and humans, to the freedom that is offered through the availability of computers to a much wider group of people by creating this project--the One Laptop Per Child project.

Nicholas Negroponte takes the podium.

NN: When I went to architecture school, I had a professor that said “What you lack in talent, you make up for in gall.”

LC: Negroponte went to architecture school?! Did I know that?

NN: Part of my career was to be in the right place in the right time, and I didn’t necessarily have to worry about whether someone thought I was wrong or stupid, and that was a badge of honor and I could prove them wrong.

When I was in high school, I had done pretty well in math, and I won the art prizes. I decided what I should do was go to architecture school. And again, maybe an illustration of gall, I went to see the headmaster and told him this.

I told him I decided I’d study architecture because I did well in math and in art. And he said “you know, I like grey suits, and I like pinstripe suits, but I hate grey pinstripe suits.” But that went over my head and I went to architecture school, which was wonderful! But it took me a while to figure out that the intersection of those two fields wasn’t necessarily architecture--it was computers.

In architecture school, what I learned was not to solve problems but to ask questions. And when I look at my colleagues at MIT in engineering, they think of themselves as problem solvers. They use the world problem solving interchangeably with design.

I’m going to take you through a quick lifetime: I went to MIT as a freshman in 1961. Before affirmative action, it was a rather incestuous institution where you were a student, then went on to become faculty. Habitat was built in 1967, and as students we were all moving cubes around. Moshe Safdie was an influence for all of us.

So my first computer program looked like it came from this era--and remember, this was backed up by a multi-million dollar computer that was larger than this room.

And we built robotic devices that built Habitat-looking structures, and put it in a museum and filled the glass box with gerbils! The theory--really pretty lame--but the idea was that as the gerbils move the blocks, it was intentional. And the robotic arm would pick up the blocks and put them in certain locations and you could return to the museum and the blocks would be in different places. It was well reviewed and got some praise, but then we got into some trouble. It turned out that the robotic arm’s magnetic part would sometimes get a gerbil stuck in it. A gerbil is a flexible thing, so it’d run off and be okay. And we did this all with impunity.

On to 1977: It took about five or six years at least for me to build up a lab that we called the architecture machine group, after the book. And it started to do things that were a little less frivolous. One of them was to build something called a “media room.” Which looks a little old fashioned, but for the first time ever, it was a space you could where all the computing … it had quadrophonic sound, seamless floor to ceiling displays, probably a couple of million dollars of hardware running the room.

What we developed, it was the first display that didn’t just have graphics, but it had images. If you wanted the calculator you touched it. If you wanted the calendar, you touched the calendar. And people thought it was ridiculous. People argued againt touch sensitive displays because you would dirty the displays. and I would say, no, in some cases you would clean it.

LC: like the gerbils-robot relationship.

NN: But most importantly, it was spatial. It was a spatial data management system. I would ask “How often did you say to your assistant, ‘go into my office and look at the paper on the third shelf on the left?’” People do remember things pretty well spatially, and that was the idea here.

NN: We had these video discs that stored the video in concentric rings, and you could randomly access them. Since it was controllable down to the frame, you could build an interface around it. So here it was a sitcom where you could interface with it and not just change language and go forward and background, but things that were unheard of. The geometry of the disks was such that you could actually video--in this case we chose Aspen because you can go down the streets and make every turn--sound familiar?

LC: Drew, I guess all this is a well-trodden history for you?

DH: Yep. This is all founding Media lab history. We still talk about these original projects. The Aspen project is one that has the most modern resonance. It’s interesting to try to understand why some of these projects have clear modern analogs and some seem totally lost.

NN: You had two video discs, and you’re driving down the street. When you get to an intersection, you could go left or right. And it was seamless because we filmed the video forwards and backwards and you could run it either way.

NN: When you take somebody into the lab and show them an image you can touch or that can say things--you could noticeably hear people sucking in air…[it was a big deal.]

NN: You could say “Put that, there” and people were awestruck. It was so visual and so easy to come and just spend a few minutes. The then president of MIT, whose office was nearby …he was the last president of MIT to have a chauffeur. It was really convenient for him to bring guests by the lab and show this to them, and then take them off to lunch. I got to know him really well.

NN: I got to know him well, and when he got ready to retire, he said “I’m not going to become chairman, but I want to go back to the lab and do research again. But there isn’t a lab for me.” And I said “I’ll build one for you!”

7:00 pm: NN: A touch sensitive display that also picks up pressure, not just pressure into the screen, but there is enough friction to pick up forces on the screen. That still hasn’t picked up, but touch certainly has.

By this time, we decide to build the Media Lab. At MIT, if you want to start a lab, you have to build a building. Partly because everyone wars over space, and if you have your own building you don’t have to do that. The faculty in the first media lab had one thing in common. They didn’t all come from architecture, but they all came from departments that didn’t want them. It was really a salon de refusés. I remember going to see the then-provost of MIT and saying “I’d like to include Seymour Papert in the new media lab” and the provost said “Bless your heart!” Very creative people are not the easiest to manage, and so a lot of the people who joined the Media Lab were affiliated with all sorts of schools. Many came out of architecture and planning because we hosted the arts, and that was our first venture.

We opened our doors for business in 1985. Steve Jobs was our kick-off feature. You won’t believe this, but our caterer was Martha Stewart. She wanted the job so badly, she hadn’t quite hit the radar yet. It was quite the opening!

It eventually grew to 500 people if you include everyone. What it had in common was that they didn’t have to raise money--I did that. They didn’t have to teach. I begged them, “just do your research, design, and do whatever you want to do, and the students will come in and be a part of it.” It changed over time, but it worked. From the institute’s point of view, we were not just the golden egg, but the goose. I was never on campus as I was always out fundraising. I was out and Michael Douglas was in my class, and he asked if I could show him around--and I could hear a student asking: “who is that with Michael Douglas?”

So I was sending checks back to the institution and not getting in people’s way. They were doing perfectly fine stuff, and it didn’t matter if my cover story matched. If they came to the lab, they didn’t compare what I said to what they saw. They just saw a lot of passion and lots of enthusiasm. They said “Where does it come from? Why don’t my kids have that? Why doesn’t my staff have that?”

We ran out of space and built the second building.

The building got going when the economy started to tank, which didn’t work out quite as planned. It’s next door to the original Media Lab. As soon as we took this step, things started to change. Not just economically, but they changed partly because I’d been there so long.

The change wasn’t just that I should get out of the way, but also that it was my turn. I had been mailing checks back and I didn’t have a pet project or a group--and I said “it’s kind of my turn.” So my work became One Laptop per Child. So in 2001, this project started in a village in Cambodia. It was pretty remote for a long time - you couldn’t get there without someone in front of you checking for land mines.

I looked at this picture of kids in the village with laptops and asked myself, what about this picture won’t happen with normal market forces? I ask myself every morning if what I’m working on would happen as a result of normal market forces or not? And if it will happen anyway, I don’t need to work on it.

But the laptop, that seemed like something that wouldn’t happen normally. So we started the One Laptop Per Child project. It started with enough momentum--we raised $30M dollars to do this in a few days. It was a few phone calls.

LC: That must be nice.

NN: People just queued up to be behind it in the beginning. The idea was sufficiently outrageous that you could build a $100 laptop, and that it could just wind up and be connected and do all these things.

We never actually go to $100, but we got pretty close. It launched and it became a huge project--a $1B project. This was different than the scale of the Media Lab, different from a lot of things. I had no idea when it started, that it would be that important.

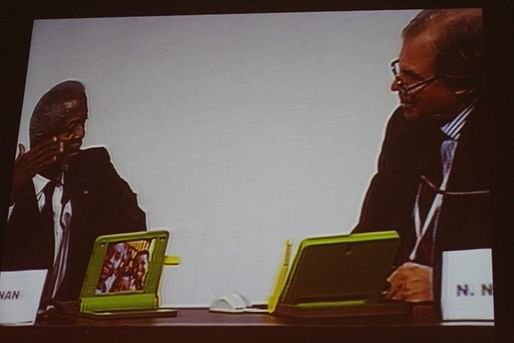

I don’t show this picture just to gloat that I launched with Kofi Annan--but to show that by being a non-profit, you could partner with people who otherwise couldn’t. And that was a very important decision: Every single friend of mine, all over the place, said “Nicholas, make it a profit making company and make tons of money and then give the money away.” And I said “no, that doesn’t sound right. Suddenly mission and market get confused, and I have a lot of trouble with the whole idea that there is a middle group of entrepreneurial do-good business.” I’m not so sure that exists.

The real test for this laptop was not the $100, or the total count, but: Does it get into the permanent collection of MOMA?

LC: Is he serious?

DH: Yes. At least in this audience. I doubt he says that to the governments that bought them.

NN: In Uruguay, every single child between 5 and 18 has this little green laptop. History hasn’t borne itself out yet in terms of economic outputs. But to me, the most heartwarming part of it is the number of kids teaching their parents how to read and write. You’re reversing the format, with kids become the agents of change. They’re not receptacles.

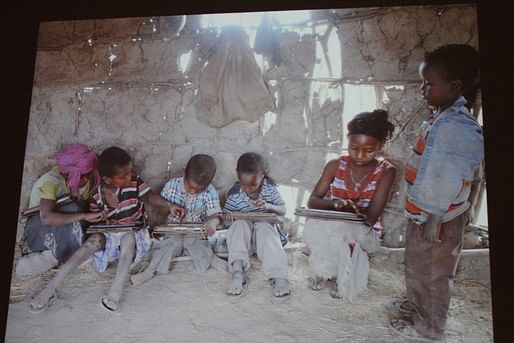

I mean, look at this kid! You’ve got to wonder what her life will be like, concentrating with that expression. And you can’t see it here, but her baby brother is behind her, also watching the screen.

This is in India. The way the teacher was used to teaching, the kids were lined up in perfect rows and the kids were silent. And if you didn’t give the right answer, you got a little fly swat or a whip, so there was no upside to answering a question. So there was a certain monotony; everyone was inert. But this is how he taught after the laptops came. This changed his view of what teaching was. He says “I have never enjoyed teaching so much. The kids come running to school now.”

In Uruguay, the president announced that every child would get a laptop in 18 months. One teacher said she couldn’t deal with it, and went to ask for early retirement. During her waiting period of three weeks, the laptops arrived--and sure enough, she saw the energy and went running back to the office to ask for late retirement. She assigned a project on cows. A student went home and told her parents that she didn’t have an angle on cows, and her father said, “you’re very lucky, because our cow tonight is giving birth.” The laptops have cameras, and she could stay up and video the cow being born. As you can imagine, the result was spellbinding.

What was important was that she was not a particular good student in the past, but there was the self-esteem of everyone paying attention to her, and she became a great student. And the students uploaded it to YouTube, and by now time 100,000 people have looked at it.

LC: So OLPC introduced a modern western approach of indulging children?

DH: Hah, yeah, not clear what her agency in all this was. But maybe we really do need those little successes to see the value in education?

LC: Maybe so.

NN: We always underestimate what children can do. It turns out there are 50-100M kids that don’t go to school because there isn’t a school. So if there isn’t a school, you have no choice. What do you do if there isn’t a school? And the only thing you can do is leverage the children.

LC: Ooh, he’s coming up on his current project!!

DH: Can’t wait!

NN: So that’s why we started two new experiments: Could you drop off tablets in a village with no instructions and no people who know about them? Just leave them there; will the kids figure it out?

The answer is yes, they will. Within about two and a half minutes the first one was open, the on-off switch was discovered. These villages don’t have electricity or television or phones or anything that has an on-off switch. This whole concept is alien. But they figured it out. The kid on the right assigned himself the role of the teacher.

LC: I gotta give it to him, this is a pretty amazing story…Though someone stayed behind to take these pictures, right?

NN: These tablets are recording every touch, taking pictures, recording everything. For those of you who are IRB sensitive, this is all IRB cleared and done according to scientific principles and morality--but the kids were being tracked. After five days, the kids were using 50 apps a day. After [a bit more time], they were singing “A, B, C.” After six months, they hacked Android.

DH: I’ve heard this ‘hacked android’ quote before. I’ve heard it was more like turning a camera on, which had been disabled accidentally. I don’t think it has anything to do with code, per se. Hard to say what it really meant.

NN: This led to the X Prize. It turns out that people spend 40x the value of the prize in order to win the prize. So the prize is $15M and it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to multiply that by 40.

...

NN: Thank you very much!

[Applause. MM and NN sit down.]

MM: Nicholas, thank you very much. I just want to go back a little to the beginning, as you went very quickly through the first part: the books, the architecture machine group. The book was written when you were just two years out of school, but it’s a very confident tone in both books. How did you discover your voice and what you wanted to do as a body of research?

NN: There’s such a risk in applying hindsight, of saying “I really thought about this as clearly as it sounded.” What was indisputable was that the studio training, the studio experience of design mapped perfectly into where computers were starting to go. They were suddenly things you could connect to. They were becoming more affordable. Since that era was happening, to do everything in a very tangible way was very natural. And to write books while it was happening, or before it happened. I felt I had to. The confidence was probably more genetic than it was real. I made up a lot of things as I went and some of them turned out to be true. Some people asked “how did you predict the future?” But I didn’t, I just extrapolated from what people were doing.

MM: But there’s a particular flavor to those books. You’re using art material and are bringing machines where the use isn’t quite clear, together with art, which suggests that there’s a poetic project--and the role of the human and the participatory. It wasn’t quite like that with a lot of people who were using computers.

NN: I’d like to say yes--

MM: So say yes--

NN: Some of it was, how many people in computers could hang out with Andy Warhol? How many people in computers had Bucky Fuller as a professor? You make that list of people who affected my life and had nothing to do with computers. I became more comfortable with writing, much later. These were very tortured books. They were belabored, I don’t crack them open now. They weren’t naturally flowing books. But I was one of the founders of Wired Magazine and I was the first person to finance it and decided I would protect my investment by writing the back page.

LC: What?! Now I understand why Wired loves the Media Lab so.

DH: Yeah, the lab really evolved with Wired as its imagined audience. We got an email every month announcing the drop-off of a giant stack of Wired magazines. Though that audience has been devoured by the internet, which has made for some turbulent times for both Wired and the Lab.

NN: And suddenly, there I did get a voice. And did enjoy it. It was a bully pulpit. People were suddenly answering my phone calls. Writing suddenly became more natural for me.

MM: And what about architecture? When you got the chance to commission the building--

NN: I’ll tell you a story about the history of that building. IM Pei is an extraordinary person, you’ve surely--

MM: He’s a graduate of this school.

NN: He’s a graduate of MIT too--of both.

MM: He did his Master’s here. [laughter]

NN: He designed an extraordinary building. It actually fit the description of what something might be called the Media Lab. But when the first cost estimates came in, they were too high. I was part of the client team and we went down with the campus architect to new york, to tell IM Pei the building was too important. And the campus architect made the mistake of trying to lecture IM Pei about the ratio of surface area and volume. IM Pei got redder and redder and finally he said “I know the most efficient building would be a sphere. And so finally he said “I’ll give you a box, will you let me cut some corners out of it?” And that’s what we got. The design was done in a fit of pique.

MM: And then you commissioned another GSD graduate, for the second building. [laughter]

NN: Well the Gehry building and Maki building were being designed at the same time. The guy in charge of the Gehry building I would exchange notes. He would go to client meetings with Gehry and tell him to calm down. In my meetings, we told Maki to liven up as he kept drawing cubes.

We went to Japan to talk to Maki about livening up, and he threw his crumpled napkin on the table and said, “this is a Frank Gehry.” He said his building would be a Gehry building inside out. [i.e. that it would be staid on the outside and explosive on the inside.]

MM: When you started the Media Lab, you didn’t actually want it to last as a long time, as it was supposed to be a short-term exercise or project. What was that about?

NN: It turns out--I didn’t know before this evening that we were both influenced by Gordon Pask--but I thought that the lab should be more like cybernetics then like electrical engineering.

Many things spun out of cybernetics. It didn’t necessarily last that many years but it was very generative and so much came of it. But it didn’t last, it didn’t enshrine itself in a department like electrical engineering when it grew out of physics. But it’s almost harder to end institutions than start them. So that’s that.

MM: How did you establish any kind of method of evaluating the outcome of the work? You were off raising money, and how did you know if the stuff coming out was any good?

NN: You’ve probably run tenure cases. While people might not say this the way I’m about to say it, but let’s face it, you get tenure because of fame. If the world knows about and talks about what you’re doing, that’s the measure. Not just because it was in the New York Times or on TV, but was the world talking about it? It’s not perfect, because fame can be fleeting or penetrating--but that was the rule of thumb. And if money keeps flowing in, somebody thinks it’s interesting.

And remember, nobody was funding the Media Lab to do something in particular--it was discretionary research where the funders had no control over what was being done. So those were my metrics. They sound superficial and maybe they are, but history has been a bit on my side in that things have spun out of it.

MM: If you had to start the Media Lab today, what would you do differently?

NN: Certain things happen because of where things coincide in history, and this was so locked into that era and the people. We just hired a new director a couple of years ago who is so different than any of us were--he was 44 when we hired him, a 44 year old Japanese dropout who was Timothy Leary’s godson. What more could you ask for? But his world is bottom up, and immersed in social media, different than the one of the founders. So today, the Media Lab wouldn’t be as elitist.

MM: Don’t you think that things like the definition of the building, the fact that the resources to run an operation like that have to be quite substantial. That they sometimes prevent the kind of freedom or ease of doing things that you had at the beginning. That it de facto institutionalizes the nature of research.

NN: Yes, it does institutionalize it. There are certain hazards. Some come from the demographics of it. When we started it, everyone involved was over 60 or under 40. I was 39. What happens is that 30 years later, guess where that block is. You have different demographics, a different dynamic today than we did 25 years ago. But I’m not sure it would happen today in any way that looks or feels like what the Media Lab looks or feels like. I think back at that period and also one has to keep in mind that nobody else was doing anything else that even looked like it. But now a lot of people do things that look like it. To be a pioneer is to enjoy a certain license that you lose as more and more people start to do what you do. You want that. But then you need to go off and do something else, something edgy and different. It’s sort of unacademic; you tell faculty at some point that you should go off and do something else.

7:47 pm: Dean Mohsen opens the floor for questions.

Q: How do you decide which X Prizes you want to support?

NN: I’m only involved with one, the learning X prize. There have been about five historically. There are 3 or 4 more cooking. The historical ones have largely been related to outer space. Or one going on right now, the moon lander prize. I’m not involved with any future or past ones. But I was asked to help them think about the learning prize. And at one point, someone said “would you run it?” And that’s how it happened.

Q: If you were to start a lab at Harvard, what lab would you start today here?

NN: I’m not sure there’s anything generically harvard, that I would pick because it’s Harvard versus some other place. But it’s really about the people, and who you are and what you want to do. You have to understand that MIT as an institution, but it’s something like 80% research and 20% teaching. That is tilted because of Lincoln Laboratories is a huge center of research. It’s a more common phenomenon at MIT and the labs will come and go and start up and it’s very entrepreneurial in that sense. The last department we eliminated at MIT was nutrition; it’s not a fast changing organization. And I think of Harvard as being different than MIT in that sense, of how much research is done instead of teaching.

Q: I couldn’t help but make the analogy between OLPC and things like the Raspberry Pi Foundation; putting together a very cheap machine and making it available to kids. How do you see these other projects in relation to OLPC?

NN: Raspberry Pi is a more techy...almost hobbyist approach to making computing affordable and flexible.

LC: Burn!

NN: They got themselves a little stuck with Linux. As we did too, by the way. But it didn’t start from the same point of view. It wasn’t trying to anyway be humanitarian. I thought you were headed in a different direction. The most common criticism I got was “Why a laptop when people don’t have clean water or reliable food sources?” No one asks Raspberry Pi that. We would ask people if they changed ‘laptop’ out for ‘education’ and whether their complaint still worked - it usually didn’t.

LC: That’s an interesting hypothesis.

DH: I don’t think that defuses the question; auto-assuming that laptops are equivalent with other educational spending seems like the ACTUAL criticism that people are making.

NN: Microsoft and Intel went after the project with a certain vengeance.

NN: The people I admire in actual leadership positions … I’ll talk about someone I admired who was a good leader. It was Chuck Vest, two presidents ago at MIT. And leadership with him was the person who you came out of a meeting with them walking on air, feeling good about the future directions. They were maybe his directions, but I admired that. People who led in ways you didn’t necessarily notice. In hindsight, I hope that it was like that. I watched people like Steve Jobs have tantrums, and it obviously had its good effects, but it was very different. I prefer to be more transparent.

Q: I’m going back to a couple of questions ago, when you were equating technology with education. Can you extrapolate that to a computer taking the place of education in the case of a place like the GSD or the Media Lab?

NN: What I’ve come to believe recently is that there’s a huge difference between education and learning. That education is a little like banking, and learning like economics. Something basic. You can’t have a strong economy without banks. But there’s something basic about economics and finance that is more fundamental. Education as an institution is very different from learning. For the first years of our life, we do lots of learning without education per se. If you look at countries like Finland, which is getting lots of acclaim recently. There’s no testing. There’s no homework. Reading doesn’t happen until the second grade. And you say “wait a minute, this seems like a vacation.” It’s the exact opposite of what’s happening in a lot of Asian countries or in this country. So I’ve always thought of technology not as a tool of the institutional side of the equation, but as a tool for learning through play or learning by doing. Technology as a means of expression not as a tool of transference.

You get things like the MOOCs going on now or Khan academy. It’s just not part of the equation here. At early ages it’s totally separate.

MM: But have you been involved with edX?

NN: When Harvard got involved with MITx I was excited. But as you get down in lower and lower ages and I look at something like that and I say “how could Khan Academy be even remotely celebrated” because almost everything it’s doing is wrong. What isn’t wrong, what’s kind of right is the flipping of the classroom. But the rest of it is just off the wall. That somebody would think they could write all the material? That’s like Brittanica starting up in the wake of wikipedia. It doesn’t make sense. That you could confuse low production values with simplicity. Or that you could read a book on a subject and then give a course on it. So many things seemed wrong. You don’t have to be right for the technology to be right. Especially in the institutional side.

Q: Going from the Media Lab to OLPC, which makes you vulnerable to a critique which has to do with trying to save the world. Even if there are no such intentions, it still has ideas of colonialism. So I wonder if you could talk about that? As architects and others move out of their disciplinary domains, what they should keep in mind?

NN: It was a dramatic change. And there was no ambiguity, I was trying to change the world. That was the mission. Colonialism is a separate issue, we can have that discussion for hours. At the Media Lab, my role was to be a light bulb. My role at OLPC was to be a laser beam. Everything had to do with getting to that dot. I would jokingly tell people that my horizon used to be ten years and now it’s ten months. It was very very different. Non profit, supposedly saving the world, but it was totally different behavior. Complete contrast between the two.

The XPRIZE is now between the two. There’s lots of energy from people, and you’re not trying to focus the laser beam. But it is in a particular area, where we’re trying to create momentum.

I will meet people who are 55, 60 years old who have had enormously successful careers in whatever it may be. Banking, business, whatever. You meet them at a cocktail party, what do they talk to you about? They talk to you about their experience in the peace corps. What they remember very often is that for some period in their life they did something like that. And that for the next number of years they did very well, but find themselves looking for meaning again. And having to separate meaning and money is a very unfortunate circumstance.

LC: First world problems! But I admit I totally agree with him.

NN: Today, a lot of young people trade money for meaning. And they will do things are more meaningful than their parents did, and there will be a little more harmony between those. And I think that’s terrific.

Q: What about the potential of labs to scale up and replicate in different geographic contexts? I remember there was a period when different ‘Media Labs’ were operating. One in Europe, one in Asia.

NN: There were five or six of them.

Q: Can you share some thoughts about that period?

NN: What they all had in common was that they were all failures to one degree or another. You’d think you’d learn after the first one, or the second one. But none of them ended particularly well. There’s something relatively unique--and not just about the United States and Cambridge and MIT--but there are certain things we take for granted that are very comfortable here. I found myself arguing in those other places for things we took for granted here. It didn’t work for one reason or another. I hope we don’t try another. But maybe today with the networked society it could work better. But it sure didn’t in the past.

Dean Mohsen wraps things up.

MM: It was wonderful to have you talk about your history with such openness and frankness. I do think this area of what research means today is a big conundrum. It’s true that the first part of the work was more open-ended; it didn’t have an instrumental end. And when you then decided to have your own time, your own lab was highly instrumental. It has research consequences but it’s about impact. In a school, we’re caught in the tension between the idea of research as something that has this open-endedness, and the idea of impact.

For me, some of the questions people are asking have to do with disciplinary knowledge. I think there’s also the belief that this somehow becomes a part of architecture, that it adds to the body of knowledge. I don’t think this problem is solved yet. I’m really excited by the way in which some of these ideas relates to the way in which one works and investigates in architecture.

NN: I live three blocks away!

MM: Yes, we will continue this.

Applause. End.

Thank you for reading!

Drew and Lian

The full Architecture Machine Group reunites on November 21st at the new Media Lab for the opening of Futures Past: Design and the Machine. Please join us for further discussions!

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

1 Comment

That gerbils-robot piece/project from early in his career sounds amazing...

also his point re: tenure is interesting (and maybe has to do with later difference he illuminated between MIT / Harvard in terms of lab / teaching percentage) given recent discussions re: how peer reviewed vs other forms of digital publishing in relation to academic advancement.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.