Hi Archinect,

We're in full, full Piper tonight for Toyo Ito's lecture. (You can watch the full video at the GSD's YouTube Channel.)

From the GSD website:

The Metabolist Movement in the 1960s established the foundation from which contemporary architecture in Japan has emerged up to the present. Even today, the visionary architectural and urban projects created by the leading Metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake continue to shine brightly, according to Toyo Ito. In this lecture, he will consider Metabolism’s significance today through his rereading of Kikutake's works of that time.

Toyo Ito was born in Seoul; after graduating from the University of Tokyo, Department of Architecture, he worked at Kiyonori Kikutake Architects and Associates before establishing his own office, under the name Urban Robot, in 1971. With Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects since 1979, Ito has completed many notable projects, including the widely published Sendai Mediatheque (2000), Tower of Winds in Yokohama (1986), Tama Art University Library (2007), and Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture (2011). "Ripples," a metal street furniture piece, won the Compasso D'Oro, the prestigious Italian furniture prize, in 2004. Toyo Ito's many awards received for architecture include the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, at the 2002 Venice Architecture Biennial, and the Golden Lion for Best Pavilion, for the Japanese Pavilion at Venice in 2012.

6:30: The hobs are nobbing, and students are crowding the aisles.

6:38: Dean Mostafavi calls things to order. "It was some years ago that I asked Ito-San a favor; to help provide an introduction to Kikutake-San." It was a special day when they met, MM reminisces, and he comments on Kikutake-San's great smile and humor.

6:40: Kikutake-San's widow is here, and MM asks her to say a few words. After bowing deeply, she thanks MM and the school for hosting the exhibition and lecture; then begins to tell us about her late husband's gentle spirit. "He would find an autumn leaf, and take it home, to sketch it. If there was the moon was out, he would be inspired by that. ...That was the gentle side of him, but maybe later Ito-San can tell you that in the office situation, he was very, very strict. There was yelling and throwing of things, and [everyone would have to] work for many days without sleep." She mentions, as has MM, that it's fitting that Toyo Ito deliver these remarks about KK's work, as KK admired Ito's work greatly, and vice versa. "Mr. Ito has spoken very kindly, and honestly, about my husband's work."

6:47: MM is talking about the Japan lecture series from last year, and about the Tokyo studio which took place last year with Toyo Ito to work on issues related to the recovery from the tsunami.

About Toyo Ito, MM says: His fascination with our contemporary culture, especially the impact of technology on our bodies and hence our experience of the environment...[deals powerfully with] our current condition." ...Unlike the output of many other successful architects, which whether deliberately or not relies on a stylistic continuity, Ito treats each project distinctly. For Ito, modern man is a Tarzan...body and architecture are in a constant state of flux in their negotiation with the modern city. Ito's work. Ken Tadashi Oshima will be translating.

6:52: TI: "...It is a great honor to be speaking here about my teacher, Kikutake-San."

The image that MM showed [above, with page number 412 in the corner] was taken about a year before his death (which was just under one year ago); we had hoped to have the exhibition while KK was still alive.

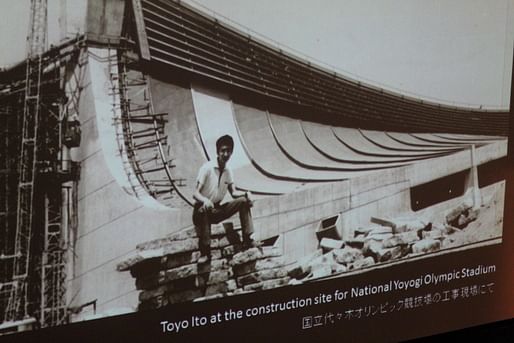

This image was in my fourth year of school; I spent a month as an intern in KK's office in the open-desk system. The Olympics was the next year. One year into working in KK's office [above]; "I was the slimmest I was ever, 15kg less than now."

6:56: In introducing the legacy of modern architecture in Japan, we can see the influence of Le Corbusier on this group. Maekawa worked for Corb; Tange worked for Maekawa. Maki, Isozaki, and Kurokawa all worked in Tange's office or in his university laboratory. I worked in the Kikutake office between 1965 and 1969. Kazuyo Sejima, in turn, worked my office...

6:56: In introducing the legacy of modern architecture in Japan, we can see the influence of Le Corbusier on this group. Maekawa worked for Corb; Tange worked for Maekawa. Maki, Isozaki, and Kurokawa all worked in Tange's office or in his university laboratory. I worked in the Kikutake office between 1965 and 1969. Kazuyo Sejima, in turn, worked my office...

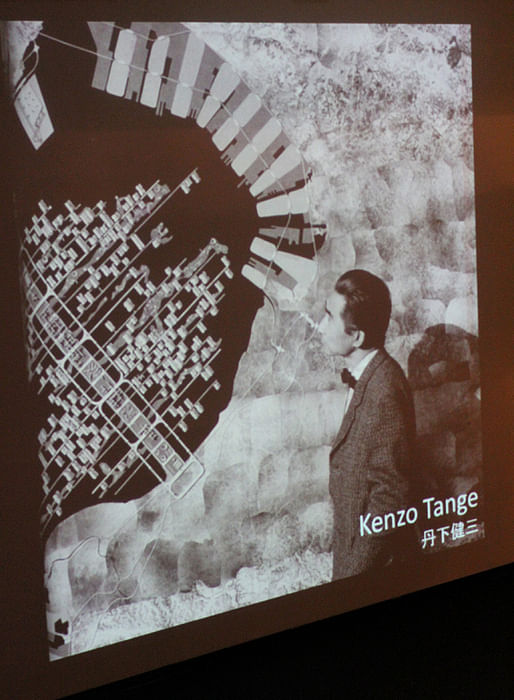

6:59: Kenzo Tange was really busy at the time for the Olympics, so he only came to the university one or two times that year. So his impression of Tange is as a dandy, with wide-bottom pants and a bow-tie.

When TI was a third year, this magazine came out and was a big inspiration for him.

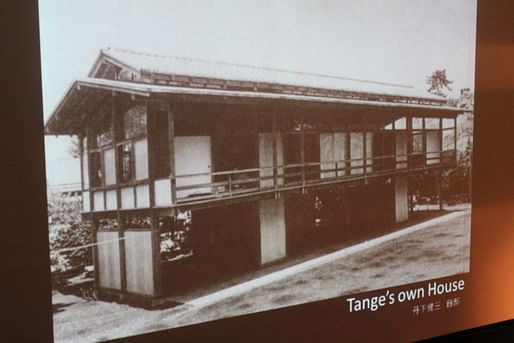

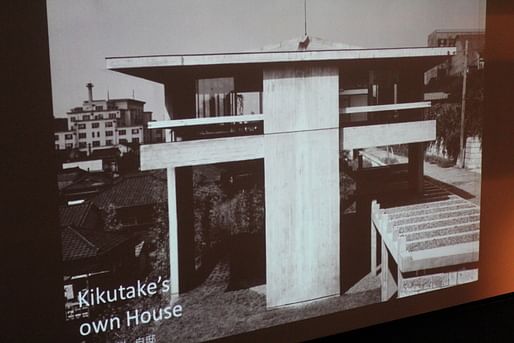

7:01: Now I'd like to make a comparison between KK and Tange. Here's Tange's own house in the outlying areas of Tokyo. In comparison, KK's house is dynamic and bold, and has a raw energy. Pilotis, wall planes. Here we see the main space suspended on pilotis, and the characteristic of KK's work is that it's raised up high, floating.

7:01: Now I'd like to make a comparison between KK and Tange. Here's Tange's own house in the outlying areas of Tokyo. In comparison, KK's house is dynamic and bold, and has a raw energy. Pilotis, wall planes. Here we see the main space suspended on pilotis, and the characteristic of KK's work is that it's raised up high, floating.

We can see the difference, between Tange, the sophistication of the Katsura Villa, as contrasted with the way KK looked towards the rusticity of Japanese traditional houses. KK's influence on TI is perhaps that [TI] now "sees sophistication as the devil." We can also see the tremendous influence from China that is borrowed and refined.

One might see this as impoverished or rural, but from the prospective of the farmhouse (it was central in the control and administration of the land.)

One might see this as impoverished or rural, but from the prospective of the farmhouse (it was central in the control and administration of the land.)

7:08: A large difference between KT's plan for Tokyo Bay and KK's Marine City. KT's is a really urban scheme, the literal extension of Tokyo into Tokyo Bay. In the Marine City, it is a city, but around the water, almost a garden city.

Here we see Tange's Kagawa prefectural Government building, which TI admires most. In contrast, KK's plan for the Kyoto International Conference center, is a path towards the shrine. On the left, the refined; on the right, the dynamic.

Here we see Tange's Kagawa prefectural Government building, which TI admires most. In contrast, KK's plan for the Kyoto International Conference center, is a path towards the shrine. On the left, the refined; on the right, the dynamic.

KO corrects the English translation on this slide; it's actually the opposite:

KO corrects the English translation on this slide; it's actually the opposite:

Columns set off space, floor defines space.

It's about the space that emerges from around a column. In KK's work, the floor-platform is often elevated, and defines that space in a particular, lofty way.

This shrine is in Ito-San's hometown, with a revered column rising up.

This shrine is in Ito-San's hometown, with a revered column rising up.  Note the four pillars rising up in this old drawing (in yellow). Sacred space is defined by these pillars.

Note the four pillars rising up in this old drawing (in yellow). Sacred space is defined by these pillars.

The column is replaced every seven years. These people almost live for this festival every seven years.

The column is replaced every seven years. These people almost live for this festival every seven years.

This is a prime example of the floor plane defining its space. Both KK and TI very much admire this work.

This is a prime example of the floor plane defining its space. Both KK and TI very much admire this work.

7:16: Sky House: this is the clearest example of those four pillars raising up a space towards the sky.

7:16: Sky House: this is the clearest example of those four pillars raising up a space towards the sky.

We see here [above left] the square plan with a half inside, half outside interstitial space. As an expression of the metabolist thinking, you can see the primary living space, unchanging, while the kitchen and bathroom change quite a lot over time.

We see here [above left] the square plan with a half inside, half outside interstitial space. As an expression of the metabolist thinking, you can see the primary living space, unchanging, while the kitchen and bathroom change quite a lot over time.

The proportions of the space are key.

The proportions of the space are key.

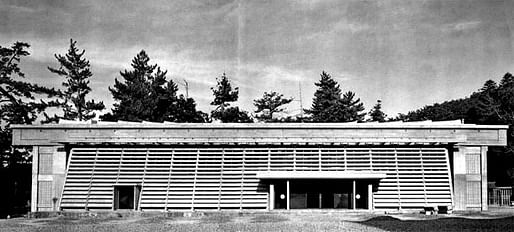

During this period, Marcel Breuer was influential, especially in the use of horizontal louvers, but here you can see vertical louvers, as in a farmhouse.

The children's room, shown above, hangs from the main mass. KK considered it a failure. (I didn't catch why.) Here is a clear example of KK building on industrialized technology to create this hanging "movenett."

What TI finds profoundly interesting is that while this was the period of the perfection of mass industrialization, KK goes to the rural, agrarian ideal of the farmhouse. Rather than pure theory it's the power of the space.

Here's the Izumo administration building. A few years ago, TI visited and felt it was amazing that it was built half a century ago but even today has an incredible power. The precast panels express rice before it's harvested--the louvers resemble a rack where rice strands are cut and dried, as below:

Under construction--you can see the video of this in the lobby, a video which TI saw today for the first time. A 40m span, impressive.

Under construction--you can see the video of this in the lobby, a video which TI saw today for the first time. A 40m span, impressive.

Here we see the clarity of the overall composition, and the refinement of the individual pieces.

Here we see the clarity of the overall composition, and the refinement of the individual pieces.

In the shadow space [in the above image, highlighted by laser-pointer] is glass that was imported from France. This is the louvered wall where you'd see the water drip down, almost like a waterfall. Kikutake-San would always talk about the systems...in the arrangement of the stones; it wasn't a mechanical composition, but a human one, felt in the assembly of the elements.

This iron gate, designed by a graphic designer (Oshi?), depicts clouds.

This scheme happened when TI was in his third year of college, and was truly influential. Quite a shock, but unfortunately not realized.

This scheme happened when TI was in his third year of college, and was truly influential. Quite a shock, but unfortunately not realized.

In this plan, we see the building is lifted up, as in the sky house; that distance to the ground and the circulation was probably a reason why this scheme did not win. But when you look at the drawings on display (in the exhibition), especially the detailed section, it's truly remarkable. You can see KK's passion in these drawings that are almost like working drawings, despite it just being a competition. And it recalled traditional roof bracketry.

This is a small scale hot spring area. It is a simple yet complicated composition that faces the ocean. There's a shinto gate-like structure, and floors above that define the space, with hanging spaces below, together with the elevator and stair shafts beside.

In this great model you can see that principle of the columns activating the space and the floors defining it.

In this great model you can see that principle of the columns activating the space and the floors defining it.

Compare with this very strong Shinto gate that is supported by sub columns.

Compare with this very strong Shinto gate that is supported by sub columns.

TI was able to see this just as it was completed, at the time of the Tokyo Olympics.

TI was able to see this just as it was completed, at the time of the Tokyo Olympics.

Pacific Hotel Chigasaki. It goes without saying that this was somewhat of a realization of the Marine City.

Pacific Hotel Chigasaki. It goes without saying that this was somewhat of a realization of the Marine City.

We see the metabolist thinking in the plan, with the sloping roof and changeable bathroom units on the exterior.

We see the metabolist thinking in the plan, with the sloping roof and changeable bathroom units on the exterior.

This is a really memorable experience for TI when he was in his fourth year of college doing his open-desk internship. This was a time when the project was just starting up and KK asked TI to research the area. He did a month of research and presented the results on the final day. It's at that time when he asked to work for the KK office and got a "yes" answer.

This is a really memorable experience for TI when he was in his fourth year of college doing his open-desk internship. This was a time when the project was just starting up and KK asked TI to research the area. He did a month of research and presented the results on the final day. It's at that time when he asked to work for the KK office and got a "yes" answer.

Going to the office to work, he was quite shocked to see the actual design [below]. It's difficult to explain what this design is all about. We see this accordion-like roof, but more than this, there is a fixed ground plane and covering that floats above. ...At this point he began to really understand that bodily experience of the space, that tremendous intuitive sense of design.

It's difficult to explain what this design is all about. We see this accordion-like roof, but more than this, there is a fixed ground plane and covering that floats above. ...At this point he began to really understand that bodily experience of the space, that tremendous intuitive sense of design.

Synthesizing the lessons from KK:

We can see his particular sensibilities in going counter to modernism in many ways, in its anti-symbolic notions of modernism.

This is not the place to fully explain this, but...here you can see those principles of the mesh columns forming that space, and the platforms of the floor forming that distinctive plane.

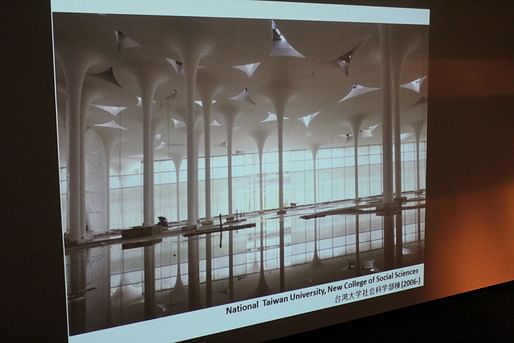

Here we see the New College of Social Sciences in Taiwan that will be completed before the end of the year. Plant-like columns.

Here we see the New College of Social Sciences in Taiwan that will be completed before the end of the year. Plant-like columns.

This is a new mediatheque that we will start constructing this year, that is two levels. Here we see multiple centers; not columns, but a whirlpool-like energy.

This is a new mediatheque that we will start constructing this year, that is two levels. Here we see multiple centers; not columns, but a whirlpool-like energy.

Here we see the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House that Dean Mostafavi was a juror for. This might be the most un-KK-like scheme we've seen today. Here the column and floor and wall have all been melted into one.

Here we see the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House that Dean Mostafavi was a juror for. This might be the most un-KK-like scheme we've seen today. Here the column and floor and wall have all been melted into one. It's been under construction for 6 years and hopefully will be completed within another two.

It's been under construction for 6 years and hopefully will be completed within another two.

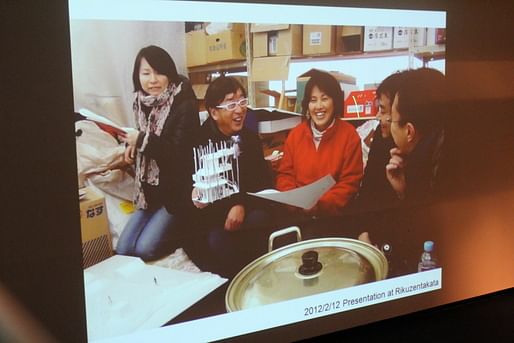

7:54: To end I'd like to talk about the "Home-for-all" in Rikuzentakata. This project emerges from a group of five architects that came together to do work for the relief in the disaster. Separate from that group, TI worked with three young architects. In the back of the mountain, you see the site.

It is a small house for people who lost their houses to come, eat, and talk. Here we see the three 40-something architects: Fujimoto, Inui, and Hirata. It was a real struggle to decide what direction to go in, because of the many ideas [below].

It is a small house for people who lost their houses to come, eat, and talk. Here we see the three 40-something architects: Fujimoto, Inui, and Hirata. It was a real struggle to decide what direction to go in, because of the many ideas [below].

Here we see the woman who was the catalyst in bringing everyone together [below]. She herself lost her home but put that energy into bringing everyone together. Through her efforts, we started to see what the direction of the 'home-for-all' would be.

Here see these colorful floats that emerged in this gray context, enlivening the space for the annual Tanabata festival, with towers that come up, enlivening all the people.

Here see these colorful floats that emerged in this gray context, enlivening the space for the annual Tanabata festival, with towers that come up, enlivening all the people.

In contrast to the horizontality, we see the vertical columns, which are cedar trees that were damaged in the tsunami, that are reused. With these nineteen columns brought back to life, to be a symbolic home for these people. In April, construction began.

During the festival, the column raising festival took place.

In the Venice Biennale, we displayed the whole process. The photos lining the walls are by a resident of the area who lost his home.

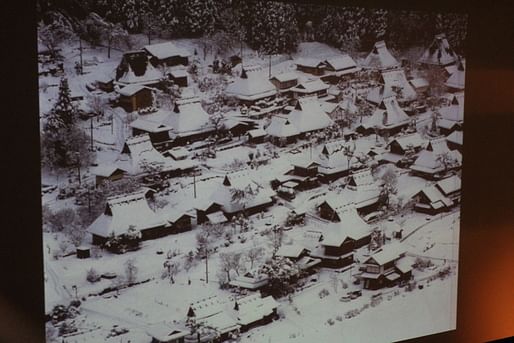

Here, I'd like to reconsider the nature of the agriculture landscape in KK's work. In his latter years he spoke about how Japanese culture was formed through agrarian culture. The farm is situated between the terraced rice fields, as an infrastructure.

A close relationship between inside and outside.

KK would talk about how tools and furniture came from this farm culture.

KK would talk about how tools and furniture came from this farm culture.

We can perceive the importance of re-examining these landscapes that might have disappeared for various practical reasons, but that especially in this period after the 3-11 disaster, become important.

This woman that we saw who lost her house, she had a normal livelihood, but through this disaster emerged an almost primited motherly force that transfixed the area. This primitive architecture emerged from this primitive-like force that emerged from people's responses to the tragedy.

TI perceives the need to rethink these fundamentals; what is the village--what is the future paradigm? And he looks to this model of the agrarian foundation.

At this point, how I see KK's metabolism, is not as an industrial future, but in this natural context, shaped by natural forces, and is organic and metabolic and changing in that way.

Thank you very much. [appause]

8:09: MM asks about how TI started and almost ended with the single-family house. "The problem I see with the village or single-family house, is that it doesn't have the organization structure that is implied by the larger-scale." In the recovery from the tsunami, we don't have time for each family to bulid their own house; there's the scale of the government helping rebuild, which is more at the scale of the metabolists.

TI: "It's a very difficult question, but it's interesting to see Rem Koolhaas' project. In the interviews, we can see how in the 60s is the idea of the nation-state, appealing to the country. When you look at the broader picture of the metabolists, especially Tange, you see them riding international currents, but it's only KK where you see a real push for traditional culture. It was really the difficulty of approaching the metabolists, and seeing the international push within the national context, as opposed to this other current. In observing KK's work, you see him really becoming an independent voice; it's not about expressing Japan for the sake of Japan. It's looking to the reality of what it is, especially at the small scale. So, it's really in his perception this smaller-scale, felt, bodily architecture; so it is a particular perspective.

MM: "I can continue, but...please, go ahead."

Question from the audience: (couldn't hear exactly, but it was asking TI to compare KK and another contemporary figure in metabolism.)

(The answer is several minutes long; I feel sorry for Mr. Oshima who is translating!)

TI: Both Shinohara and KK were my highly respected elders. ...In looking at KK there is a sense of connection to society from the inside, working from within the social context. In this post tsunami era, it's especially important for architects to have this perpsective, which is often missing.

Question from the audience: Metabolism was incredible in the way that the architects came together around a particular theoretical project; is that possible today? And what is the role of theory today in Japan; is there such a thing as Japanese architecture?

TI: This problem is not only one in Japan, but one could perhaps say it is in the USA as well. It was truly a unique moment in the 1960s when there was this energy that emerged, but that quickly changed in the 70s, in the failure to realize the kind of utopia that was envisioned. Seeing those failures, and the capitalistic market took over. So, as Rem Koolhaas talks about in Project Japan, this project we see today in the metabolists was this glimmering moment that we spoke about today. As a student I was taken by this whole movement, but that has disappeared. At this moment, it's important to see the social component of architecture and to think about what is truly possible in this broader sphere.

Question from the audience about raised spaces.

TI: Of course you can see this worldwide, especially with Le Corbusier's use of the pilotis and raising the ground plane. But in Japan this is also from ancient times, from the raised storehouses that were intended to keep grain dry. In the contemporary urban context this is especially difficult, and he's looking to this other, agrarian paradigm.

Question from the audience: It seems difficult for any young architect today to take up a reflection on the vernacular? Do you see this being taken up outside of disaster relief situations?

TI: Even before the disaster, I believe this needed to be rethought, in the relationship between inside and outside, and our relationship with nature and the environment. After the earthquake and visiting the disaster areas, it's seeing this love and this look towards the agrarian context that people really strove for. That was impressive and really moved TI. It was not just as an elder architect, but even younger architects who went to the area felt that sense. So it's not about moving towards traditional architecture, but to rethink the relationship to the land and region, which is important in the 21st century.

MM closes the event. "One of the things that's been very inspiring is that the Venice Biennale project, collaborating with Fujimoto, Inui, and Hirata, opens up the notion of relations and friendships, and it allows Ito-San to be the maverick that he was when he started his firm--as an urban nomad--and to try to do that now in the farmlands. So good luck, and move ahead with this new project, and new friendships and new affiliations, from which we can all learn." [applause]

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

5 Comments

Incredible. Thanks for sharing Lian!

always enjoy these.

I really enjoyed this. I thought I knew alot about Japanese Metabolist architecture but this was good. Contrasting Kikutaki w Tange had a lot of sense to me w Kikutaki clearly the more visionary. I can also see, barely, parallels in the work of Kurokawa, especially his writings on architecture.

I am so impressed by the Japanese Metabolist architecture. Thank doe the informative posting.

Definitely learned something with this lecture - thanks for posting, Lian!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.