Since the beginning of the year I have been wanting to write something expanding on what I meant by Critical Activism in my '09 prediction. The following is a first DRAFT of an essay I am writing describing what I see as an emerging practice model. Influenced by Allison Smithson's 'How to Recognize and Read Mat-Building', it is partly a manifesto and partly a look at a trend in contemporary practice.

I will not have time to really work on it until after thesis ends, so I wanted to share it while still relatively close to the feature that inspired me to write it.

A few weeks ago a senior GSD administrator, after hearing about my

thesis and

precedent studies, plainly asked me if I wanted to “just be an activist.” I am not sure what he meant but it seemed a clear example of the academic and professional anxiety that still exists around activism. Regardless, the comment made me question what it would even mean to ‘just’ be an activist.

First, I wanted to understand the anxiety around activism. The roots, as is often the case, seem to come from modernism. From Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin, to Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxiom home, to many other proposals, designers promised a brave new design world. This world would be one of egalitarianism brought upon by technology and expressed through urban and architectural design. We now know that this modernist brave new world never arrived. The people who architect’s thought would arise to take their place in an egalitarian modern society instead arose against the modernist housing blocks and moved to nostalgic homes in the suburbs. Thus a period of heavy involvement, even activism, by designers ended. Since that moment, activism in design has had a patina of utopian idealism and even mockable hippieism.

However, we are once again facing some major changing conditions, such as ever expanding suburbs and urban slums. Design professionals that have staked out their positions in those issues have so far been seen as in the periphery of the profession. The best among them, have learned the lessons from earlier efforts and seem to be rethinking the meaning of activism. Looking at designers like Teddy Cruz, Marjetica Potrc, the late Sam Mockbee, Urban Think-Tank, and Elemental Do-Tank you begin to see just such a rethinking.

The work by these and other designers begin to comprise an emerging movement of critical activists. The elements that tie these practices and characterize ‘critical activism’ include: 1) active practices that rely in new funding and organizational structures and collaboration; 2) active involvement in exposing political, social, and economic conflicts; 3) active proximity in the institutions that can help solve those conflicts; and 4) a desire to architecturalize these conditions with active designs that rely on inhabitant participation. The next few pages will take closer look at each of these items.

Active Practices

In the current model of practice the architect waits for a single client with the appropriate funds to give them a project. This leads to a profit driven system making the architect subservient to the myopic whims of the market. This system is simply not flexible enough for architects to engage the built environment in a way that can change it.

The practices identified as part of the critical activism tackle the problem of practice in two ways. First they find a new organizational structure and model of financing. Estudio Teddy Cruz (ETC), Rural Studio, Urban Think-Tank and Elemental are all tied to academic institutions while holding a non-profit status as well. This set-up allows flexibility in the identification, design, and financing of projects. Second, this firms are open and seek active collaborations with design professionals and practitioners from other disciplines.

Marketic Potrc

Marketic Potrc in collaboration with

Urban ThinktankActive Involvement

Often the first step in solving a problem is recognizing the fact that it even exists. The critical activist practice plays that role for the design field by exposing conflicts in the built environment. They show emerging problems and point them as possible places for design inquiry.

They differ, however, in the way they expose those problems. Marjetica Potrc uses the gallery as a place to confront people with the reality for millions of people world-wide. Teddy Cruz tackles two scales, first he identifies a ‘political equator’ that separates the global south and north. He then specifically maps this condition as it occurs in the San Diego - Tijuana border. He does this by mapping the condition as well as a series of other art projects and installations. Urban Think-Tank exposes the conditions in Caracas through videos and books.

Estudio Teddy Cruz, Political EquatorActive Proximity

Estudio Teddy Cruz, Political EquatorActive Proximity

It is of course not enough to simply expose the problems within the built environment. These practices seek to change the conditions. To do so,

critical activist firms seek to engage the institutions that can bring change to communities in need of it. These institutions include: the academy, government, financial institutions, and the legal system.

Teddy Cruz, for example is involved and partners with developers and social non-profits from the very beginning of a project. He has also lobbied government to change codes when they conflict with designs. Similarly, Elemental engages institutions throughout the design process. However, they also create new institutions that turn inhabitants into ‘active partners’ after construction is completed.

Política Stereo: Política Habitacional: De clientes pasivos a socios activos from

elementalchile on

Vimeo.

Teddy Cruz, Casa Familiar

Active Designs

The final, and perhaps more important, element that defines critical activist practices is (inter)active designs. This is mainly expressed through designs that require involvement by inhabitants. Elemental, for example, built only half a house for the residents of the Iquique housing project. Each tenant was then free to finish the other half as finances and time allowed. The result is that all the inhabitants have the basic infrastructure needed in all residences but have the freedom to finish it to their liking.

Teddy Cruz has used similar approaches in projects with Casa Familiar and the Maquiladoras. Urban Think-Tank has gone as far as to propose naked skyscrapers in the Barrio Vertical project.

Iquique Housing

Iquique Housing by Elemental

_________

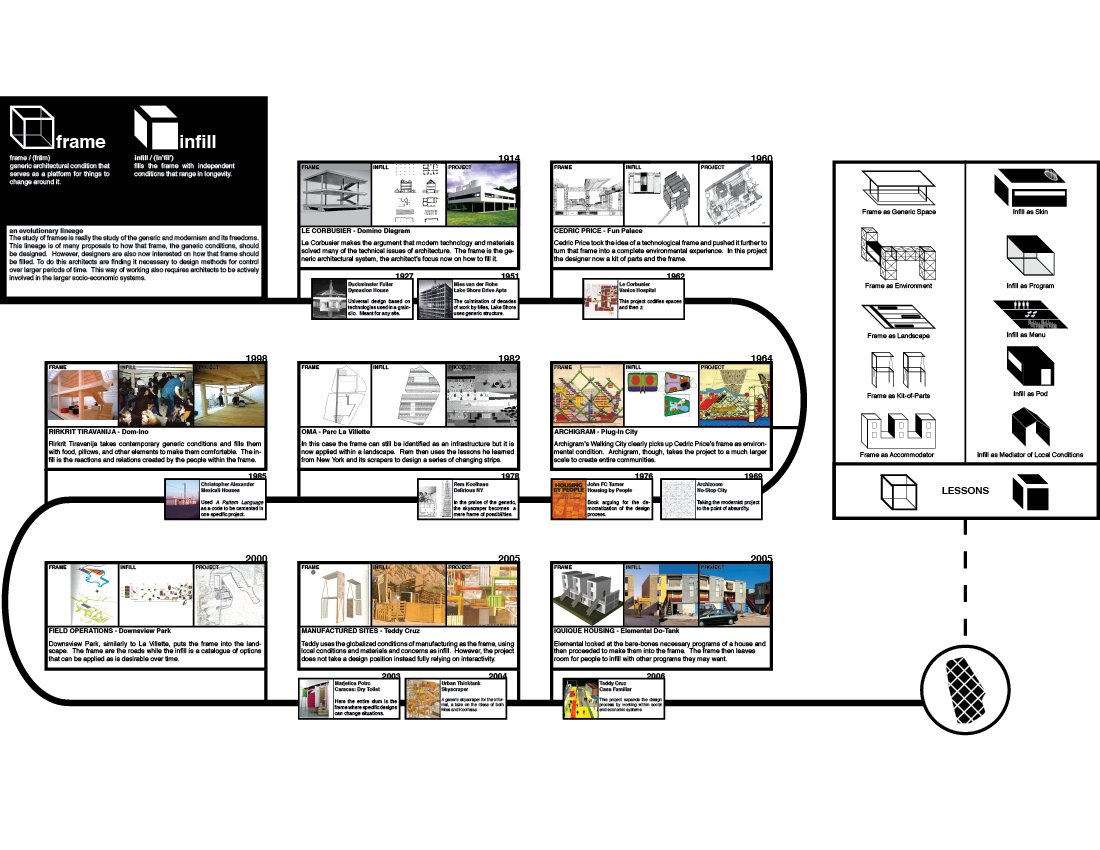

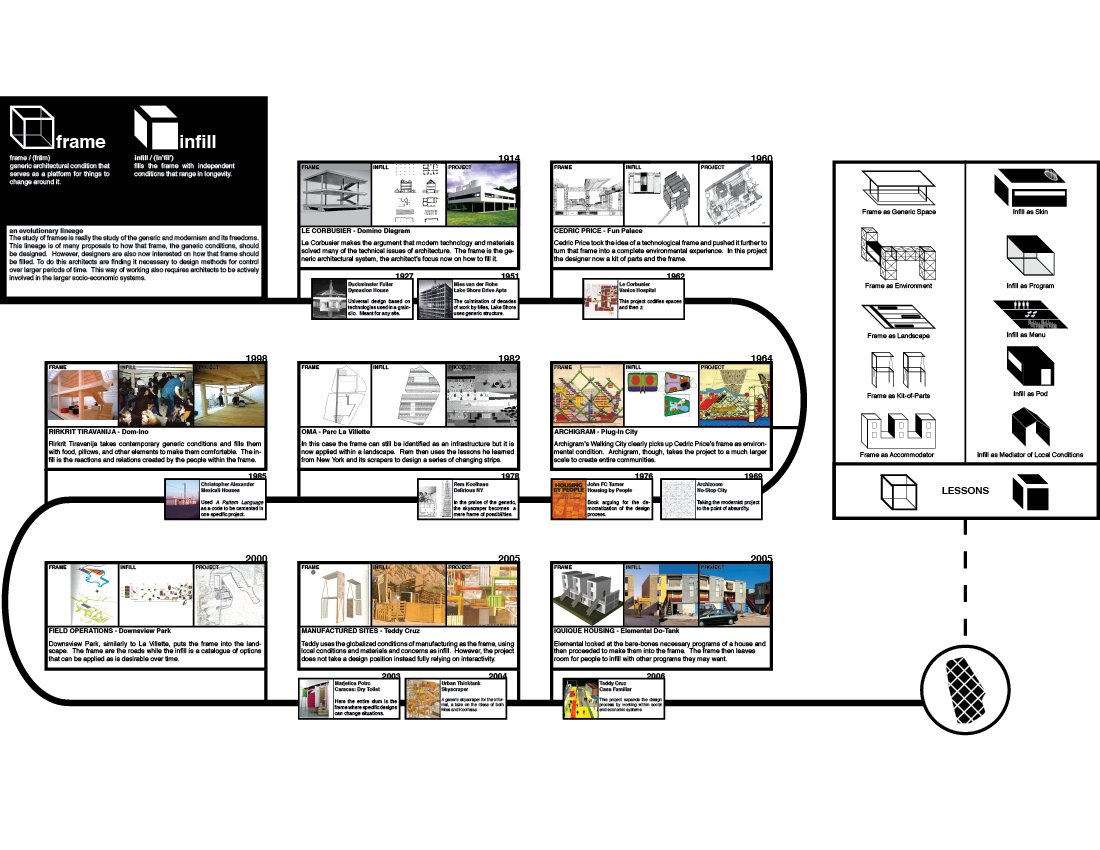

Related to

Frame and Infill Study

Marketic Potrc in collaboration with Urban Thinktank

Marketic Potrc in collaboration with Urban Thinktank Estudio Teddy Cruz, Political Equator

Estudio Teddy Cruz, Political Equator Teddy Cruz, Casa Familiar

Teddy Cruz, Casa Familiar Iquique Housing by Elemental

Iquique Housing by Elemental

4 Comments

great start there- i've got something in progress along the same lines, but i never seem able to finish it- add this to the things we should talk about sometime!

I know! Are you going to be around during spring break?

yes- working on two papers, but we'll figure it out.

A few weeks ago a senior GSD administrator, after hearing about my thesis and precedent studies, plainly asked me if I wanted to “just be an activist.”

Did you ask this person if they wanted to "just be an architect"?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.