Hi Archinect!

W. Gavin Robb is presenting his M.Arch thesis, “Roots Run Deep: A Tomb for Manfredo Tafuri."

The tomb and the sublime are closely linked.

Relation between technology and buildings at this scale.

Empathy: a tight fit between a body and its space.

Instrument: a domestic scale and an infrastructural scale.

And strange things I found in Appalachia: machine/building hybrids. From the bottom up they’re designed scientifically in terms of how to move a lot of matter. On the other hand they’re vernacular, and unselfconscious, though highly architectural.

The classical body is static; the modern body, on the other hand, has a mobilized eye.

As such: The classical marked a place between earth and sky, producing a static body. The modern hovered as a sky-platform above an earth-plinth, which produces the body reduced to an eye, vapor. The thesis slips the body in along the infinite laminations of earth and sky, producing a, plural, colloidal body…inscribed by hieroglyphs of telephone wires. The interface between technology and the body.

Tafuri is an exercise in continual overturning, opening up the door for history to enter back into critical architectural discourse. He found something in Piranesi, for example, that he brought into the future. The fold. The sharpness of the fold. There is a continually uncured mind, that is never totally settled.

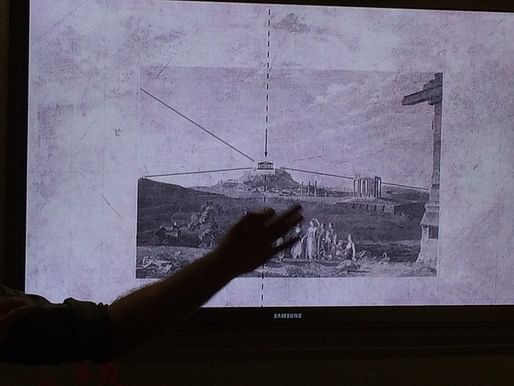

Centralia, Pennsylvania is an incredible place. In 1962 there was a mine fire in an open pit mine, and it’s been burning since then. They estimate it’ll burn for another 500 years and there’s no way to control it. The town is deserted, with noxious gases, though a few holdouts still live there. The lines of the streets are in the trees, but there’s nothing there. It’s casually true, but only as an instrumentalized fiction.

The town traverses a valley. Thinking about a tomb, the first move is to dig an 800 foot trench. In order to be contemporary, I’ve taken void as the principle, instead of solid.

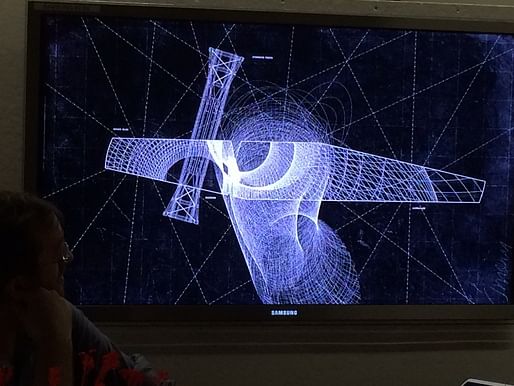

The surface of the project is just circles and lines. The forms here are described … all straight lines in another non-euclidean space … laminated to our reality from another reality along three straight lines.

The tomb is an instrument that you enter into and encounter with your body.

The long axis is the line of windmills.

So it’s very rational; there’s a floorplate, stairs, there’s a truss.

The 1pm gnomon line of the solstice aligns with the … sky axis in the tomb. So on that day the sun comes deep into this pit. So there’s an instrumentality to the project and I hope to convey that deep within this subterranean space, there is light that penetrates down.

These objects are ancient futures; they could be from the past or from 10,000 years from now. I think our relationship with technology is one that allows us to connect with mythic and cosmic forces with alarming ease, utility, and syncretism. I think architecture has to take seriously this interface with technology, and try to translate it into its own language. To survive at all, we have to connect back to the deep roots of the earth.

Michael Bell: You talked about the how and the what, but I’m still wondering about the why.

GR: I think architecture exists at a strange scale we can empathize with, bodily. Our relationship with technology has shown us that a lot of things that we think are impossible are actually quite simple. So I think we can combine these two ideas, taking this as a challenge.

Robert Somol: I see a thesis that depends on technology while critiquing technology, and I’m not sure where you’re trying to connect. This seems to be a Lebbeus Woods/Tatlin Tower aesthetic. Who are the theorists who would bring back the body? You’ve got the trifecta of tragedy: tomb, Tafuri, Centralia.

K Michael Hays: One of the things that the match of crude and cyber technology does for me, is that it suggests there is something much more primitive that had to happen before this could arise. I also want to know how seriously you want to think about this as the new sublime, but one of the things the old sublime did was…allow us to think about things outside our understanding, things that were anterior to us. To me the archaism here evokes something anterior.

RS: I’m not sure about the difference between the anterior and nostalgia.

GR: I think this is actually outward facing, not inward facing. I think that anterior is present in the land and architecture is something that can bring it into being.

Mark Jarzombek: I feel like that there is a missing cinematic world would help me…Klingons on a mining planet underground…In the beginning, that beautiful [gospel] song, evoked labor and the idea of people digging this pit. There’s a Hollywood quality to it.'

GR: Well, if you want to talk feasibility … [Laughter]

GR: I think the fact that there’s this primal, uncontrollable fire underground is part of this. That otherworldliness is already present.

MJ: The other thing that comes to mind is Zoroastrianism. GR: Yes. MJ: Why do you say yes?

GR: Zoroastrianism feels appropriate…I hadn’t started there, but the idea of two forces overturning each other. Do you want to convert? MJ: Yes, I want to convert. GR: How can I help you?

MJ: My final point is then: I could imagine an operatic, Mozart-ian, enlightenment sensibility.

KMH: It seems to me that the relationship between the architecture and the earth is crucial. We assume that the digging, the fire, and the architecture are continuous, especially since the alignments are found from the site.

GR: Does this section help?

KMH: It does, but it seems to me that the earth should be more part of the architecture.

Katy Barkan: If the architecture is the shell, it’s metonymic. If we go down there, we’re burning up.

GR: I’m interested in an architecture that our body projects itself onto, and something that transforms our body. Honestly, it’s been a balance of the mimetic and instrumental. I’m not sure I succeeded. The tension between moves that architecture makes itself and moves that bring you into it.

KMH: Is it all about light? It seems that one of these funnels has to be venting the gasses.

KB: And that makes that space inhabitable. At the moment it cannot be.

GR: Well each of these tubes has a double layer and the stair is captured within it. This one gets down to 4’ wide, so it’s close and tight. So there is an interior that’s not just vast…

RS: The death of thesis was to generate the idea, and then put your project where you got your idea from. Studying interesting alleys and putting your project there. I think this project suffers from that a bit; it’s so bound by the specificities of this site. How can I apply these ideas when I’m building a library in downtown Boston?

GR: I’m interested more in the processes; I’m not advocating that this form be transported to another site.

Felecia David: I’d add: How are you reconstructing the body? You gave this really interesting definition.

GR: A star alignment is an optic thing; the eye. The stair and having to jump, is a haptic thing.

FD: Somehow the making of architecture and your understanding of the body have to do with a reciprocation of materiality, and this experience. When we look at something optical, it sounds like a different experience.

GR: I just mean that the eye is part of the body.

FD: But there’s a kind of working precision in how you’re working which is really interesting. The body is of the earth, and technology is part of us—it’s not an alien thing, but there’s a back and forth and the boundary expands.

GR: I think this way of working—there are conditions out in the world that are strange and that can be activated by architecture.

KMH: I think Bob really damaged you when he called this “dead tech.” There was a time when all of Thom Mayne’s students projects looked like the underside of bridges. Some of us can’t get past that image. If it dematerialized a little more and became more about the tracing of outside influences.

GR: I agree. This rendering [above] isn’t quite right. I don’t want to make a technological excuse, but…it’s hard to render something ethereal. The drawings and model are more fine. The building is wedged in there and balancing.

MJ: There is that Schinkel-Mozart-Light-Zorastrianism…I’m not literally saying that an opera might be a better design model than the tomb…but it allows you all sorts of freedoms.

KMH: What I’m finding with a lot of thesis projects — and I’m not saying this one is — is that the project is the presentation. You spend a lot of time on the American gospel/worker, and I don’t know where that went, in operatic terms. Maybe that could reappear as a kind of American Mozart…

KB: In that place—it’s so f—ed up and the people who work there, their bodies are thrown away in the worst possible way.

KMH: Maybe we can think about the people as not being literally there, but as architecture serving an indexical function.

RS: You say this isn’t indexical?

RS: I think you’re not giving enough credit to House 6. The way it is constructed … full bed does not fit … twin beds

GR: Do you really think the indexical project cares about the position of the bed?

RS: It produces a condition that forces a new type of body.

KMH: In the Appalachia you were showing…I wish this proposal had that kind of vernacular, in the way that those agrarian forms outlived their use. There’s something underneath here that is generic, or bigger than this particular project on this particular site, that becomes repeatable—not as a style—

GR: The modern really chewed up the body, as you said, Katy, and I’m thinking of a more prosthetic relationship with the body that puts you back into an amicable relationship with technology.

RS: Is this the image of a more comfortable relationship with technology? [Laughter]

GR: It’s also a tomb.

RS: If parametricism is the neo-liberal, you’ve also gone back to no people, and that’s going back to an essentialism that I don’t want to return to: stardust and la la la la la. I want a more plastic, uprooted life, and I don’t want that as a kind of parametricism. To me, you’re dealing with 21st century technology through the ruination of 19th century technology, and there’s no traction there.

[Silence]

MJ: So…… you’re not going to stand up for monumentalism?

…

GR: I’m not against monumentalism and heroics, clearly. I just think architecture should break it down to a scale that we can deal with.

KMH: I think these drawings capture so much of the thing as a thing. Versus some of the other line drawings, which are more dematerialized.

Mack Scogin: I don’t think there’s a vernacular.

KMH: It’s more cosmic.

MS: Yes. And even the place, I’m not sure there’s much vernacular there.

KB: From what I understand, you’re saying that architecture is not the ground, and that we need these things—these four stakes—but in the end, it sounds like you chose a really good site, like Bob is saying.

BS: You situate your project in terms of you having a problem with parametrics, so I want to see that as the technology you situate yourself against.

MJ: Where’s the empathy part of this?

GR: I think it has to do with the breaking down of scale, and the gathering of cosmic forces in a way that is more gentle. So I don’t think this is a brutal relationship to the body.

MJ: In some sense I have to acquiesce to what you say. The project in some way is about Mankind with a capital “M,” which is solitary or generic. Most of us thought that “mankind” died 20 years ago, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be recuperated. Maybe the absence of irony is genuine here on your part. You’re really a believer, and I’m sort of impressed. I never would have expected this in a million years.

RS: It was funny when you said, “I have to talk about Tafuri,” and a few sentences later, “I have to talk about geometry.” When I think about GSD, I think about geometry and Tafuri.

Robert Pietrusko: I’m reading this project in another way. [Technology constructs entities that are not “other” or “anterior” but, in fact, present. You can imagine someone going in there thousands of years from now, and seeing the celestial bodies that the project frames, and catching a glimpse of the “nature” constructed through the technology of this lost civilization. Though it may be experienced in solitude, it’s an evocation of the collective.]

GR: Yes, I absolutely agree.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.