Hi Archinect,

I’m at the GSD for thesis reviews—Anya Domlesky is presenting “HOT ROT: A Breakdown Manual” for her MLA degree.

Landscape architects should be not just the apologists or ameliorators for solid waste, but active agents in the procedures of dealing with waste.

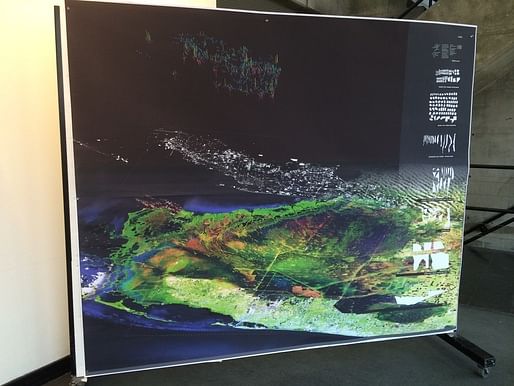

The site is South Florida, in hurricane afflicted areas, and the debris generated by these events. Hurricanes have to do with collective generation, because unlike municipal waste where the onus is on the individual, this is a shared event.

The way that waste is dealt with now in an emergency is that rules are bent. The President declares a disaster, funds are made available, and waste is quickly cleared to the periphery. The Army Corps of Engineers may help, and there are only a few sites across a large region where the waste is taken (landfill, incinerator). Outside of normal jurisdiction, this waste can be disposed of in almost any way, including burning, although the EPA is trying to improve this.

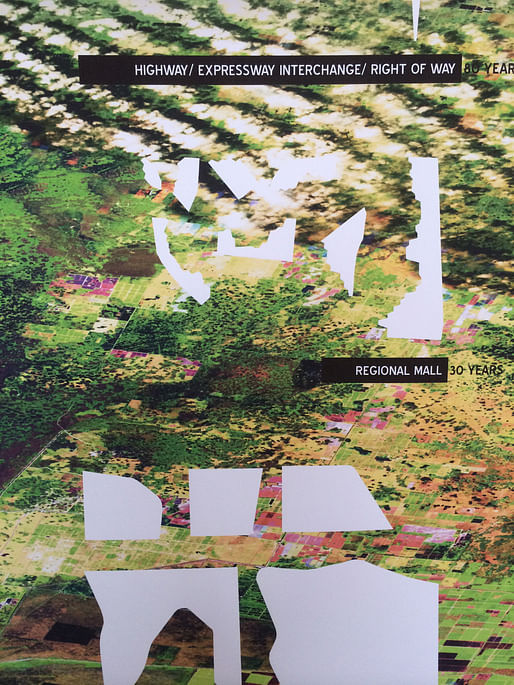

Anya selected a set of eight sites in terms of their potential for debris generation, the kinds of vegetative debris that would be found, and the clearance routes (network of roads).

Four of the sites are organized in terms of temporal opportunities, and four are determined relative to spatial opportunities. For example, for a mall that generates a peak of waste around the Christmas season, the proposed intervention is a berm. At an agricultural site for tomatoes with a fallow season, an intervention adding fertility to the ground is proposed. In a high density residential and commercial site, where developers wait until the land becomes more valuable, an anaerobic method of waste degradation using shipping containers is proposed. A fourth site relates to the touristic season.

In terms of spatial sites, there’s an infrastructural site related to interstitial spaces left over by highway interchanges; a low density residential site; a recreation site; and a medium density residential site.

Hurricane debris does not require that you deal with hazardous waste.

Gary Hildebrand (“It’s very beautiful. My first question is about the logistics of this—it’s a nightmare. Who will sort this stuff?” AD: There’s a difficulty in moving between the public and private spheres. All of the federal government funding goes into the process of managing, reducing, and hauling the waste. The funds are available and it’s primarily a matter of re-routing those funds, temporally and spatially.

Gary Hildebrand: “Isn’t there a technical difference between money that’s locked up and only released in case of a catastrophe, versus the steady allocation of budgets?” AD: I looked at what agencies would work in this area, in Miami-Dade County, who have funding and who might be able to work in this area. GH: “This approach is consistent with the question of how you can opportunistically get value out of the debris.”

AD: Waste budgets have been increasing, so there is space to maneuver.

Caroline Constant: “What I don’t get yet is the Gordon Matta-Clark.” What he does is cut at ruins to create something really beautiful. The way you presented it, we saw opportunities in these spaces, but I want to see them in terms of substantial results. I can’t imagine how a suburban parking lot filled with those berms can be better—but I want you to convince me that they can be better. AD: In this project I was more interested in the back-end work of how you get to the point where the more typical starts, not in the result of saying this can become a giant park space, which it could.

Sergio Lopez-Pineiro (?): You should be more aggressive in space and in design. Remember the West8 project using crushed shells?

Anita Berritzbeitia: …That’s the job of a sanitary engineer. Let him or her find the places that are sinking. The front end of the project is really interesting, but because you’re setting up this criticism in terms of the role of lansdcape architects in landfills—which I agree with—I feel like you’re on the side of the sanitary engineer more than on the side of proposing a new landscape or public space that can literally emerge from that.

Fadi Masoud: What you’re doing is different what a sanitary engineer would do, because the forms you’re creating are not what they’d do—they’d just make it flat, find a way to get rid of the waste. I think if you took one of these sites and started to show occupation more, to highlight the agency of the landscape architect in opposition to that of the sanitary engineer.

Ed Eigen: What you’re distributing could either be a public good or a public nuisance, which goes back to how you described how these sites are extra-jurisdictional. They’re defined as wastelands. So your project is very interesting in this sense. It’s a strong statement to say that you’re taking up this waste from people, to make it a common good.

Peter Del Tredici: This was a great presentation. I don’t know if it’s still true, but a lot of the solid waste around Boston used to be shipped to Florida to fertilize citrus groves, because they had limited soil. The other opportunity is the drosscape of Alan Berger. The idea of burying all this organic matter is insane. To a certain extent your project is too logical—it makes too much sense!

Dilip da Cunha: …By calling attention to waste as a resource…I think your challenge is to take destruction seriously on its own terms. Can that be less product oriented and more process oriented—issues of decay? You’ve chosen to work with hurricane debris. A hurricane razes civilization as we know it, and there’s a whole language at stake in terms of coming up with something afresh. But you could also shift towards everyday practices as opposed to the exceptional.

Shauna Gillies-Smith: I was going to say almost the exact opposite. …I was thinking about a much larger, global scale, and the volume of this material that is taken from somewhere and moved somewhere else. How can this be normalized?

Dilip da Cunha: Attention to the process, not necessarily time and space as categories because there’s always time and space, calls for a different kind of visualization…

Charles Waldheim: I really enjoyed watching you frame this problem. I really respect watching you try to think through, then rejecting things that have been done. This is a novel topic and a space for action that hadn’t occurred to me—you thought it up—and there’s a consensus building on the panel about that. I think that’s OK that we don’t know what it looks like yet. I’m beginning to be persuaded by the argument around the surreal social critique. The metabolic has been so overdone that it’s hard to not associate this with that. We’re going to have to find a way to live with our former stuff, and this could be a way forward.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

P.S. Also seen around the school:

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.