Territories in Teaching

Last night, Tatiana and I braved the Long Island Expressway to visit NYIT's other campus out in Old Westbury. Yes, our school has a Long Island Campus, and the home for second class citizens (ha-ha!), Manhattan.

Anyway, the lecture event was “Territories in Teaching”, a symposium turned open discussion on pedagogy. They picked a fantastic panel, too:

.

L to R: Dean Judith Di Maio, Professor Rodolfo Imas , Moderator Nader Voussaghian, Professor Michelle Bertomen, Professor Michael Schwarting (director of Graduate Studies), Professor Jonathan Friedman (former dean)

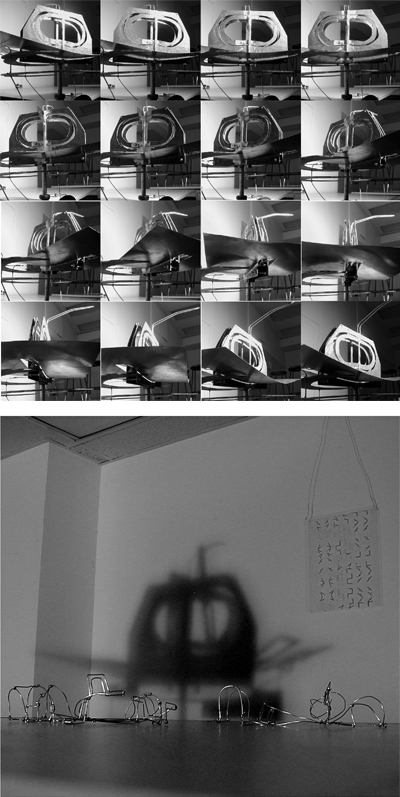

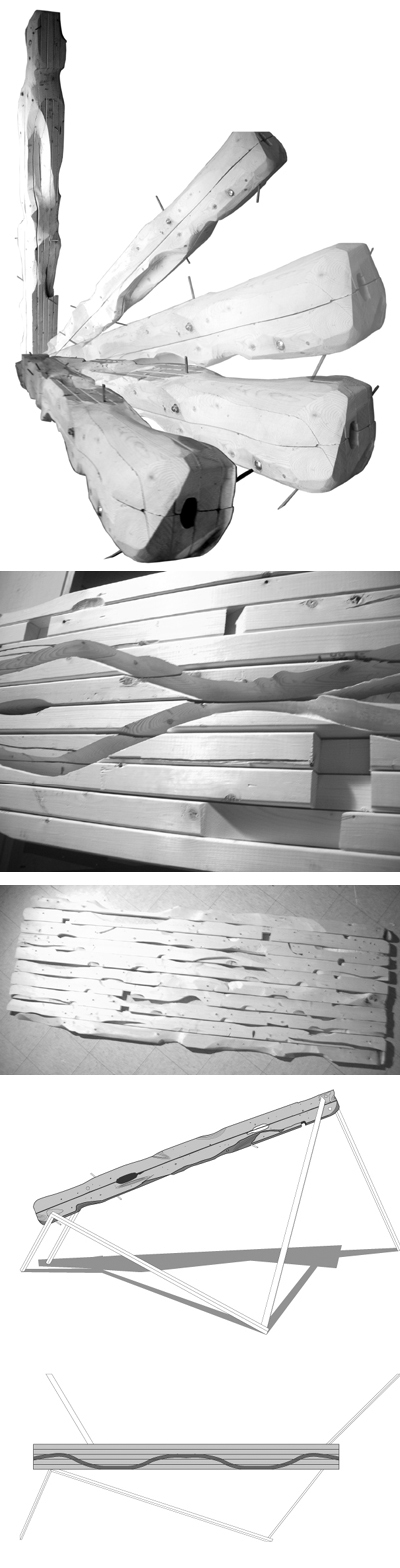

Tatiana and I went because, well...there's always the lure of listening to Imas. This is my seventh semester. I had Professor Imas for my Design Fundamentals II class and produced this:

After that, I kept going back for more. I took him voluntarily TWICE for another design studio (design a cemetery) and an independent study course (Parasite Architecture). Wild rides, all of them.

In addition, I'm always stopping by his class (and, never in an official capacity as a TA in the eyes of the school, but of my own accord). Granted, people call me stupid, they call me a glutton for punishment, but it's not because I keep going back for more. I'm sure there are plenty of other reasons that I'm an idiot. Fact is, I just keep learning from the man. But anyway, on to the lecture...

It's tough to go in open minded, because we have preconceived notions of these people, whether we have met them or not. Rumor and innuendo abound. Audience members castigated the panel for having singular objectives and slants on architecture and claimed that they should always be well rounded, but I'm sure the panel was chosen as such because they all have unique views.

So, while I personally know some things to expect from Professor Imas, the other panel members were getting on his case about how he believes that culture should be removed from the projects, freeing the students from the past and the future PREconceptions that hold them back. He focuses on removing the scale of the project, because that is one factor that sometimes locks you in to ephemeral and culturally heavy projects. Professor Bertomen called for a greater responsibility to the ills of society, and was quickly labeled a “high ideal do-gooder” by Professor Friedman.

What struck the most poignant chord with me was the notion of boundaries, a topic introduced by Professor Friedman. He mentioned that you have to introduce boundaries to the students to get them to learn, to alleviate frustration and allow them to meet challenges head on. When the topic was open to student questions by the moderator, I immediately jumped in, prompting this exchange (paraphrased):

Me: “You mentioned the topic of boundaries, and how the challenge to the student should be to how to mesh their ideas with these boundaries, almost butting up against them. One thing that I learned from Professor Imas is that sometimes it is almost as important to recognize that the boundaries need to be adjusted, changed, or sometimes removed altogether. That notion of critical thinking, to me, is just as important. Sometimes the best approach and concept is that you don't need the boundaries at all.”

Friedman: “Well, sometimes you DO need the boundaries.”

Me: “Well, sometimes you don't.”

Friedman: “Imagine basketball. You have a court, you have rules. You have to play within those rules.”

Me: “Right, but imagine on that same court, if one day they invented baseball, and they tried to play there. How would those boundaries affect that game, and how would the game affect the boundaries? It'd be something else completely.”

Moderator: “Next question!”

So, see, I didn't even get to ask the rest of the panel about boundaries. I recognize the fact that there are limitations in the real world, and while I appreciate the approach in studio of pragmatic and realistic project, I'm willing to pass at times on that approach during school. Will it get me a job? Dunno. Will it make me a better person? I know it will, but I suppose that's up for debate, too. What I did know is this: school is a great opportunity to explore architecture, perhaps making studio projects theory (and vice-versa), full of thought but NOT necessarily places that people live, etc. etc. I make buildings (the noun) in structures classes and building equipment, and at the office. I build (verb) in studio. I mean, should an approach like mine be so frowned upon?

One day I want to grow up and have an architecture education. Do I want to be an architect? Maybe. Maybe I'll be something no one has ever thought of or given a name to, and that would be even better. I just know that this is the education that's right for that.

5 Comments

the extent to which we are able to say anything depends on our ability to be understood and for this i'd say we need boundaries and preconceptions.

baseball on a basketball court doesn't mean no boundaries it means reinterpreting boundaries, and whether or not it's fun to play, good to watch, well that's about whether the interpretation "works" or not.

imagine playing monopoly where one by one, piece by piece, square by square, one note at a time the rules are removed. not replaced, removed. i think at that point you're not playing anything anymore.

righteous - you are right, but I also wasn't clear. that's my fault (I was a bit rushed earlier). the problem I have with boundaries is that, eventually, people get used to playing with them. they don't know how to function without them, and they certainly don't know how to create their own. each of my projects above started with certain constraints that were either adhered to, modified, or removed. but one thing is for certain - eventually I inserted my own boundaries.

like I said above, in the real world, constraints are everywhere. I'm not only taking extreme advantage of my time in school by taking a detour around boundaries wherever possible, I'm trying to see what living without boundaries is like. does it lead to new ways of thinking? does it allow you to see the inherent dangers of tightly bounded dictums and theory? I think that's true, also. It's not nearly as trite as "thinking outside the box." there's no box.

the danger of no boundries is this: you run the risk of never being wrong. I suppose that's so because you make up the rules as you go along. I've heard this before from people...but I disagree. considering the degree and care involved in proceeding like this, when taken and perfoemd with great responsiblity, you BECOME more repsonsible, you CREATE a new game.

You stated that sometimes its good to alter or change boundaries, and other times its good to remove them altogether - but unless you intend to return the constraints to the project, to "design without boundaries" in my opinion, just belittles architecture completely. The best architecture is about critical thinking, and about using and exploiting boundaries -- not just eschewing them in the name of "design." That cavalier attitute has been a major part of the labeling of architecture as a luxury item and has contributed to the rift between public's and the architect's perception of architecture. I suppose in the end its about what a person aims to get out of architecture. If the goal is purely private and personal in nature, fine. But if a person's intention is to actively improve the built environment - considering all the things that broad statement entails - constraints are essential to good design. to extend what righteos fist said in the above post - if you just remove constraints, after a while, its just not architecture anymore.

very nice blog entry!! well done.

yes, interesting indeed.

...

Tschumi's Architecture and Limits

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.