New research from two U.S. universities has drawn a link between socially vulnerable populations and urban heat island effect. The team, drawn from the University of Texas at San Antonio and Pennsylvania State University, used Philadelphia as a case study to summarize how more vulnerable people live in neighborhoods that are “less green and that get hotter.”

The research was recently published in the Journal of Buildings, and examines the differing characteristics of two Philadelphia neighborhoods to study how the way a neighborhood is built, and the characteristics of the people who live there, are both related to how hot it gets. The team found a “clear link between outdoor temperature and specific urban characteristics” before asking “whether these urban characteristics can be related to the social vulnerability of the residents.”

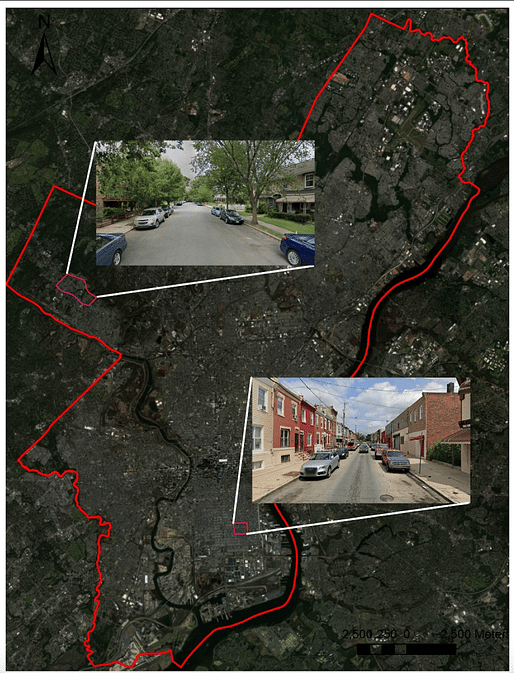

The group established a social vulnerability index for two neighborhoods in Philadelphia, which factored in residents’ housing conditions, age, education, disability, and race, among 16 U.S. census variables. The social vulnerability index showed a number from 0 to 1, with higher numbers meaning more vulnerable. One neighborhood, in Roxborough, had a number of 0.25. In South Philadelphia, the other selected neighborhood, the number was 0.98.

Using open-source GIS data alongside a microclimate simulation tool, the team then found that the South Philadelphia neighborhood contained more absorbing surfaces such as concrete, while distinctly lacking in greenery such as trees and grass, when compared to Roxborough. According to the team, such characteristics contributed to elevated leaves of heat and, consequently, higher reported levels of discomfort in the South Philadelphia neighborhood.

“Our study found that during hot and extremely hot conditions, areas with more trees had up to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) lower outdoor air temperatures compared with less green areas,” the team explained in a recent article in The Conversation. “Therefore, fewer trees and more paved surfaces, associated with the high social vulnerability neighborhood, meant higher heat exposure and less outdoor comfort for residents.”

The team’s research also went beyond surface conditions to explore other urban characteristics impacting heat, including the sky view factor, which measures the amount of sky visible from the ground. Here, the team found a link between sky exposure and increased heat.

The ratio between the building height and street width was also a factor, which determines how much shade is provided by buildings at street level. Typically, taller buildings and narrower streets offer more shade and cooler temperatures. As South Philadelphia featured low-rise brick townhouses versus Roxborough’s detached single-family homes and wider streets, Roxborough was set at a disadvantage despite its socioeconomic status.

“Our findings from Philadelphia show that urban design, material choices, and tree coverage significantly affect how warm or cool an area feels,” the team concludes. “This suggests that thoughtful planning and incorporating more greenery can make urban areas more livable and equitable. Architects can help by using lighter-colored materials and green walls and roofs.”

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.