Much will be published over the coming days about the Biennale's national pavilion winners—Spain’s “Unfinished” (with the Golden Lion) and Japan’s “en: Art of Nexus” and Peru’s “Our Amazon Frontline” (with special mentions). It is a phenomenon that conceals the terrain, limiting the perspective of the majority, and inaccurately reduces the dynamism of the lived experience. At the same time, after the fascination with the nominations wears off, it garners those passed over with a certain mystique. In the interest of representation and curiosity, then, it seems fitting to acknowledge a (very) small sampling of the more and wider.

Oh, Canada. This year, per curator Pierre Bélanger, the Canadians overcame “a list of every possible bureaucratic, logistical, and material blockade imaginable multiplied times three” in order to participate in the Biennale. With their permanent pavilion closed for construction and an agitator’s stance, the “Extraction” team’s contribution is all fight. They took on both their own homelessness and the imperial nature of their country’s global mining practices in a territorial claim of the “power ground” between the British and German pavilions. Their outdoor exhibition (see above), a sub-surface video projected through an underfoot oculus, tells the tale of architectures so extreme—the 1:1,000,000,000 scales of resource acquisition and land-forming—that all others are superseded.

Denmark, both a design heavyweight and a social welfare state, scratched its collective heads at the supposed novelty implied in the call for architectures for the public good. “Architecture depends on frameworks of political and institutional power; culture depends on architecture to reimagine manifestations of democracy,” co-curators Boris Brorman Jensen and Kristoffer Lindhardt Weiss insist with a “it-just-is” nonchalance. Together, they have assembled a three-part demonstration of what happens when the dependencies between the arts and humanism are taken as given. Their “wunderkammer” of process models gathered from architecture offices across Denmark (the “Art of Many”); their video tribute to urban design luminary Jan Gehl in his 80th year (“The Right to Space”, see below); and their slow text unraveling the installation content are a celebration of the country’s living history of everyday care and craft.

In some of the more surreal scenes of the Biennale, Romania slyly circles allusions to the aspects of social engineering that lurk within the at-large public design project. Using an absurdist aesthetic, polished but reminiscent of 19th century caravans and circuses, “Selfie Automaton” is a distributed series of sets, interfaces between visitors and seven marionette stagings (see below). Mechanized wooden puppets—tied to the stirring, pedaling, and cranking of their human counterparts—responsively dine, dance, debate, perform. They, thereby, work to instill a discomfort with and stimulate questioning of the exchange between the manipulators and the manipulated of cultural constructs.

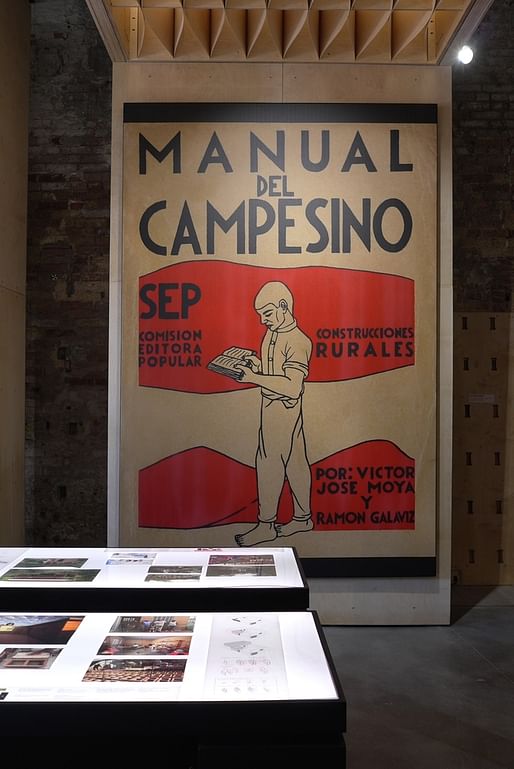

The Mexican pavilion documents the discoveries of a cross-country road-trip. On a quest to draw out the under-knowns, curator Pablo Landa set out to identify the communal and participatory architectures that quietly, but overwhelmingly, build Mexico. The outcome, “Unfoldings and Assemblages,” 30+ found projects, are presented as both didactics and manuals (see below). These exemplary works are translated as processual deconstructions that will be disseminated as self-help guides in an online database. The collection, in addition to aspiring to greater independence and sophistication in the independently built environment, also reveals morphologies in local vernaculars and traces a lineage in national communication devices through the cartoon.

The title of the Chilean submission, “Against the Tide,” refers primarily to workings out of sync with trend and the odds faced by so doing. The project, in an urban age, lives in the rural. Its content springs from primitives, a vantage rooted in origins. Both its makers and its material are raw and/or starting from scratch—students new to design and compositions of natural bounty and civilization’s refuse. The exhibition design emphasizes the potentials in these simplicities by illustrating the unexpected elegance of waste-metal—in the models of the fifteen shelters selected for display, of plastic bags; in a flowing curtain included as an evocation of trees in the wind, and for the projected image—in a theatrical arrangement of countryside depictions.

Ireland’s “Losing Myself” (above) upends all concerns for the orientation of architecture by sitting with the disorientation of dementia. Part pavilion build-out, part website, Niall McLaughlin’s and Yeoryia Manolopoulou’s research into designing for minds impaired by Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia challenges expectations for representation techniques, knocking architecture into a subjectivity of perception. Their proposal, physically, is a media presentation of confused and fragmented realities emanating from an infrastructural grid of projectors.

Designing Design

It is not just architecture’s substance that is on trial at this year’s Biennale, but also its means of presentation. The substantial number of contributions that rely on large-scale installations has sparked some debate in Venice.

On the one hand, the “super artefacts” communicate little to no explicit (presumably text-based) content. They assume either pure phenomenological appreciation, or take up interpretation (as in the case of the Swiss pavilion’s “Incidental Space”, an inhabitable cloud that its curators claim provokes existential architectural wonderings) or metaphor (like Turkey’s “Darzanà: Two Arsenals, One Vessel”, a disjointed assembly of parts resembling a ship and intended to evoke sentiments around exchanges, broken and whole, between nations) to relay meaning.

On the other hand, the more conventional “distributed displays,” Korea’s “The FAR Game”—a five-part lesson in innovative adaptation to regulation and contextual pressure, for example—miss expressing the immersive power of architecture and run the danger of coming across as overly pedantic.

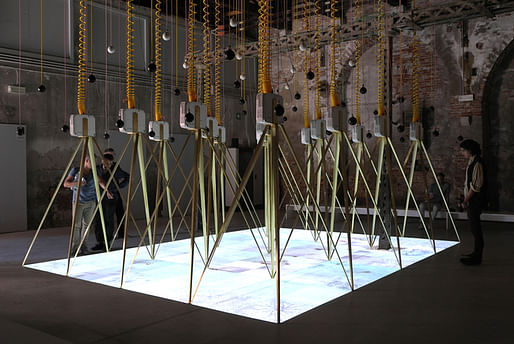

There are, of course, hybrids of these approaches. Both China’s “Daily Design, Daily Tao” (a lantern field of projects paying homage to the country’s craft past, see above) and Peru’s “Our Amazon Frontline” (a forest of graphics and objects that tell the story of Plan Selva, a collaboration between architecture and education to empower and protect the nation’s remote regions) do a good job of using narrative and information to construct a holistically experiential scene. At the same time, these mash-ups give off a waft of the unresolved.

Whatever exhibition tactic, the fervor behind the on-the-ground conversations suggests that there is something to this question of exhibition design—something that needs to go bigger.

1 Comment

Virtual reality will take this to another level.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.