Earlier in my career I was based in Chicago but I was working in Nigeria and also doing some graduate work in the summer in England.

The longest trip I packed for was 60 days in the same suitcase and it covered a month in England and a month in Nigeria.

It was a tough time in my life, but it was also kind of utopian as well because there are certain advantages to being highly mobile.

In Germany today there are 1.8 million Turks. Every year 93.5% of those people travel from Germany to Turkey at least one time, that is nearly 1.7 million Turks across all strata of society who regularly travel between cities in Germany and cities in Turkey.

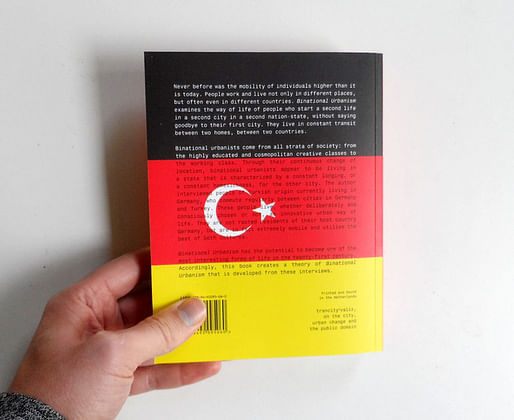

Looking at the lifestyle of this population, Bernd Upmeyer develops a theory of a new form of urbanism in his book Binational Urbanism. A binational urbanist is someone who because of the practical matters of their lives spend their time living in oscillation between two different countries. This is a thoughtful book with an interesting approach to researching the design space. In fact, after reading this book, it seems that the hybrid state of binational urbanism itself is a design space.

Drawing on interviews with a sample of Turkish people living in Germany, Upmeyer is able to extract a model of binational urbanism that is grounded in the real-life everyday experience of his subjects. Upmeyer defines the binational urbanist as someone who: 1) travels because of social connections rather than because of the city itself, 2) experiences advantages in one city that offset the disadvantages of the other city, 3) regularly moves in a circular flow between the two cities, 4) lives a decidedly urban lifestyle, 5) lives with irreconcilable contradictions as the two lifestyles clash, 6) experiences the two cites as both a local and a tourist, 7) actually finds a sense of wholeness in their identity in the constant irreconcilable contradictions of life, 8) lives in a third cultural tradition that is a blend of two different cultural traditions, 9) constantly balances conflicting lifestyles in a dynamic pulse that helps advance itself, and finally, 10) experiences a totally new way to live that doesn’t require assimilation or cultural pluralism.

Like my experience of the utopian nature of living in multiple places, Upmeyer argues that the spaces of flow in the migration journey constitute a utopian moment for the binational urbanist. These spaces of flow become the place where the traveler can leave behind the disadvantages of one city and look forward to the offsetting advantages of the other city. I remember this time in life as a moment when there were conflicting expectations on my identity, in fact I felt the multiple identities that I embodied during that time were characterized by contradiction. Being confronted with these contradictions creates cognitive dissonances and Upmeyer counts these as part of the experience of the binational urbanist. Only during movement does it become possible for these contradictions to float together in harmony, the journey is a moment of freedom, the journey and the space of flow is a third-space respite for the binational urbanist.

We think about hybridizing a lot of things in design, but building a hybrid life as a binational citizen isn’t typically considered a design space. Urban designers have an obligation to knowing their user base, and Upmeyer’s book outlines a model for doing the right kind of research that gets at the nuances of a population without neglecting the complexity of the everyday life this unique population experiences. In fact, one of the hallmarks of this book is a series of 100 pairs of contrasting antonyms that represent some of the cognitive dissonances these binational urbanists experience. Upmeyer found these antonyms by using content analysis on interview transcripts, so they are categories of experience that these Turkish people living in Germany feel in their everyday lives which means that they have a lot of ecological validity as constraints and design conditions. If you read this book for no other reason than to see how Upmeyer obtains and handles his data, you will walk away with a richer toolset for your own practice.

Using these 100 pairs of antonymns, Upmeyer looks at what he calls the “paradoxical mentalities” such as a sense of independence when in Germany contrasted with a sense of dependency when in Turkey, or the feeling of being disregarded in Germany while retaining a sense of recognition in Turkey. Or the determined aimlessness of dwelling in two places and making the most of each place, leveraging the contradictions and the affordances of places in a way that supports a higher quality of living for the binational urbanist. Having two homes leads to a sense of grounding and a sense of wanderlust and results in a state which permits the binational urbanist to live like a local and a tourist whether they happen to be in Turkey or in Germany. The binational urbanist lives in a third culture which leverages these distinctly opposed mentalities and experiences and this allows them to both adapt to the problems faced in their unique lives and to adopt a new way of living that is richer despite the challenges.

Binational urbanism is a blended mode of urbanism and that has implications on the everyday lives of the binational urbanist. If we think about the individual stories that binational urbanists experience in their daily lives, this blending of cultures will certainly have an effect on the narrative and plot development of the story. It seems like Upmeyer’s analysis gives us something new in the way that the lives of users can be understood and it seems to fit nicely with a model from contemporary cognitive science called conceptual blending (Fauconnier & Turner, 2002). In a traditional conceptual blend, two input spaces blend together and the output space is a blended concept that has some of the traits of the input spaces (not all of the traits from the input spaces carry into the blend). In our case let’s think about the two input spaces as being the two nationalities: the Turkish input and the German input, and the output is the blended Turkish/German binational urbanist - a kind of third culture. But the story begins, rather than ends, here; what carries into the blend is as important as what does not carry into the blend, and the plot advancements in the personal narrative trajectories of these binational urbanists depend on these traits as the traits unfold over time each time the blended urbanist makes a decision based on a trait they acquired in the blend.

At any point in time, the binational urbanist will find that traits which are present or absent will either facilitate or impede events and circumstances in their everyday life. In fact, cognitive dissonance and cognitive consonance in Turkish or German situations tie directly into whether or not the right trait is present in the blended culture of the binational urbanist. This can help map the points of tension, the experience of contradictions, and the trade-offs experienced in living a hybridized lifestyle. For instance, when the binational urbanist is visiting family in Turkey, at what point does a social obligation from a Turkish family member become the tipping point for the binational urbanist to long for the anonymity and freedom of their life in Germany? And how does it affect their relationship with their family? This is a tension that exists in the kinds of contradictions that the highly mobile urbanist experiences on regular basis. The strength of the traits that carried into the blend affect the course of action that the binational urbanist will take.

When the binational urbanist is living in Germany and they experience cognitive dissonance, we can think of this as a moment when Turkish inputs are clashing with the German context. When they are back in Turkey visiting family and they feel angst, it is now the German inputs that are clashing with the Turkish context. In both of these cases, the binational urbanist seeks to alleviate the cognitive dissonance by moving toward a state of consonance by whatever means are available (e.i., return to Germany, go visit family in Turkey, take a vacation, et cetera). Upmeyer makes the case that they find equilibrium in the process of movement back and forth between these states of unfulfilled expectations. That the movement itself is the utopian moment, the best of both worlds. The nuances of how blended traits play out in the process of running a blend are another study in their own right, but it is easy to see value in Upmeyer’s work for not just the design world, but also the psychological sciences.

In the end, Upmeyer’s research is able to find a theory of binational urbanism amidst the stories told by the people he studied. There is ecological validity to his assertions and he is able to generalize some of his findings into a model that makes sense as we think about an increasingly binational world. He ends the book with a section exploring this theory, tying it all together by classifying binational urbanism with ten expressions of binational urbanism that map directly to the definitions he raised in the beginning of the book.

In this final section he shows how binational urbanism is experienced as formless urbanism, compensatory urbanism, oscillatory urbanism, transnational urbanism, paradoxical urbanism, dichotomous urbanism, complementary urbanism, hybrid urbanism, dialectical urbanism and optional urbanism. Reading my own experience of living in multiple cities into this section, I found Upmeyer’s definition of compensatory urbanism to be most interesting. He describes compensation as something that offsets a disadvantage and says this:

“…although the individualism of the Germans is perceived by the binational urbanist as a disadvantage, it is compensated for by the more prevalent collectivism in Turkey. Mentalities, which are at first glance irresolvable contradictions, expose themselves ultimately as mutually compensating issues, which makes the binational urbanists ultimately independent of both mentalities. They are able to select one or the other, and change between the two as needed…Because of its compensatory effect the binational urban way of life becomes a very free way of life, which continually provides alternatives and options in each city, something one single city could never provide. Binational urbanism thus enables a rich variety of life forms and options, which conceivable could present themselves in a single city, but generally do not.” (p176-177)

I won’t give away the ending on Upmeyer’s analysis of the other nine expressions of urbanism, but know this: Upmeyer’s book masterfully untangles a knot of urbanism with a dexterity in the research that we don’t often have patience for. He untangles the knot when it would be easier to cut it out, and that act of untangling is why it matters to the design process. Each of the ten expressions of urbanism emerged from the data rather than being determined a priori and this ability to trace categories of a particular urban experience to a specific population means that any design decisions grounded in this analysis will be more meaningful for the users. His research makes design work meaningful, and he shows that it is not that difficult to do. Like I said before, if you read this book for no other reason than to learn how to do this caliber of design research, then you will have in effect taken a master class from Upmeyer.

About the author: Ryan Dewey is an installation artist and a consulting cognitive scientist. Later this year his book on spatial practices Hacking Experience: New Tools for Artists from Cognitive Science will be released from Punctum Books. You can read more about his work at RyanDewey.org or get in touch on Twitter at @RyanDewey.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.