Hi Archinect!

Tonight's event is one that I've been (peripherally) involved in, as this project is one that we've been discussing in the context of an urban planning and design seminar that I'm taking led by Rahul Mehrotra, called "Kinetic City." (Full video available at here.) From the website:

The GSD Urban India project invites the community to participate of the event “KUMBH MELA: Mapping the Ephemeral City. Presentation of a work in progress"...The presentation will include the many schools and teams from Harvard University that participated in the interdisciplinary mapping project at the Kumbh Mela 2013. Diana L. Eck (HDS), Gregg Greenough (HSPH), Satchit Balsari (HSPH), Tarun Khanna (HBS) and the GSD Urban India team led by Rahul Mehrotra (GSD)...

The research analyzes this ephemeral city from different perspectives. Being the biggest public gathering in the world , the Kumbh Mela deploys a pop-up city comprising of roads, pontoon bridges, tents of different sizes and an array of social infrastructure like clinics, hospitals, and social centers – all replicating the functioning of an actual city. The disposition of the city seamlessly articulates various layers of infrastructure and urban flows, serving apron 3 million people who gather for fifty five days and an additional 10 to 20 million people who come for cycles of twenty four hours on the main bathing dates. From the Kumbh we can learn about planning and design, reflect on flow management and infrastructural deployment but also about cultural identity and adjustment or elasticity in an urban condition of flux.

6:09: A short video introducing the Kumh, then Rahul Mehrotra welcomes everyone. He shouts out to the members of the project from Harvard's various schools--Divinity, Public Health, Business, among others--as well as the GSD students and others who have been leading out much of the work. There was a visit of ~50 Harvard faculty members and students to the Kumbh earlier this year to study the event first hand.

6:13: RM: This session is to share the progress. In August, the South Asian Institute will hold another event, with more formed research; and organizers from the Kumbh will be present then.

Since its inception, the Kumbh Mela has become the largest public gathering in the world. It provides a forum for individual and collective expression of faith, as people converge there from (around India and the world).

"Kumbh" means "pot" and refers to the myth that the festival is based on.

The Kumbh "has been celebrated for its mass appeal," though others have questions whether the event truly bridges between class divisions or whether safety can even be assured. (There was a stampede at the 1954 Kumbh where hundreds were killed.)

The Kumbh used to be an informal event, but in the 1980s, it started to be organized formally. It nonetheless touches the ground lightly, because people come with a minimum of belongings--what they can carry--and the infrastructure is generally light.

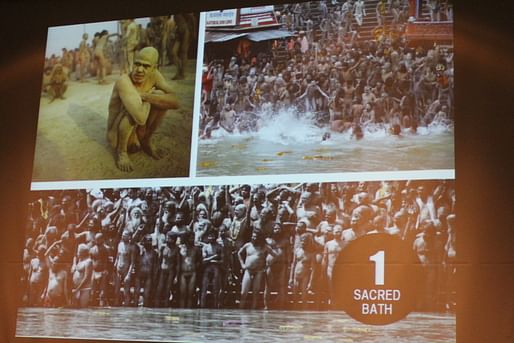

The pilgrimage culminates in bathing in the Ganges--a highly important event for Hindus.

Every tent has electricity and plumbing.

The land around the Kumbh is used for a variety of agricultural purposes between Kumbh years. The extent of the ephemeral city is different for each iteration of the Kumbh, as it depends on the geography that is created as the waters recede. "They can't even have a standard plan, because the river recedes differently each time," so this is one of the advantages of a grid that can be deployed regardless of the shape of the terrain.

Most of the documentation of the Kumbh dwells on the spectacle of the religious groups who attend the Kumbh; the Harvard project in contrast is interested in governance, cooperation, health, ephemeral urbanism, etc.

Most of the documentation of the Kumbh dwells on the spectacle of the religious groups who attend the Kumbh; the Harvard project in contrast is interested in governance, cooperation, health, ephemeral urbanism, etc.

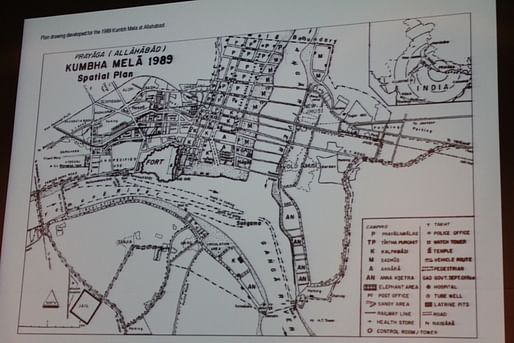

For the event 12 years ago in 2001, there was only one map that existed to plan the event. Rahul comments that it's amazing how an event of this magnitude, with all of its infrastructure, is created from such "minimal documents."

A roster of questions that guided the research; because the project was so "out of the box," the disciplinary distinctions dissolved quickly, as people felt comfortable to impinge on each others' disciplinary territories to ask and answer these questions.

6:28: Rahul notes that over the years, the urban plans for the Kumbh have reflected different trends and currents in urban design.

Various technologies were used in the mapping: photographs were geo-tagged, a photographer friend mounted a camera on a kite to take the aerial shots (the camera rotates 360 degrees every 5 seconds to capture a panorama). These images were captured over time to create a series of "before" and "after" images to show how the settlement was created.

The river only recedes in October, so the organizers have a short period of time (60 days) to set up the city. Roads are created out of metal plates that are fastened together. Pontoon bridges are low-tech but highly effective.

Above, an NGO operates there called "lost and abandoned," and they continuously announce the names of people who have been lost. Old women in particular are, sadly, often abandoned.

Above, an NGO operates there called "lost and abandoned," and they continuously announce the names of people who have been lost. Old women in particular are, sadly, often abandoned.

The event is a public-private partnership; the sectors and overall infrastructure are laid out by the government, then the occupants of each sector set up their tents and other structures within their sector.

6:45: Rahul cedes the floor to Diana Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion and Indian Studies.

DE: "I've studied pilgrimage in India for years, but never in the company of such an [indisciplinary] team."

The spot of the Kumbh is a place of pilgrimage at all times, just as India

DE describes a "somewhat smaller Kumbh Mela at Haridwar," which was about 10 million people in 2010. "Pilgrim traffic has increased, far from fading with the onrush of new technology."

DE: There is no temple at the Kumbh; the destination is the confluence of the rivers, which is the holy site and subject of prayers. It's a festival. "Young men who are there, devout, but also having a really grand time.'

DE describes a series of conversations they had with a Sadhu (known as a "renouncer" because they renounce worldly things; and are often naked), who was born in Beverly Hills and therefore could serve as a good translator and interlocutor. The spectacle of the Sadhus invites and inspires others to reconsider their lives and their own spirituality. The Sadhus have nothing to offer but their blessings.

There are many tents where there are performances that reenact various stories; Brenna McDuffie, a student who was studying these performances, found that the notion of performance was not limited to these theaters but permeated the entire event.

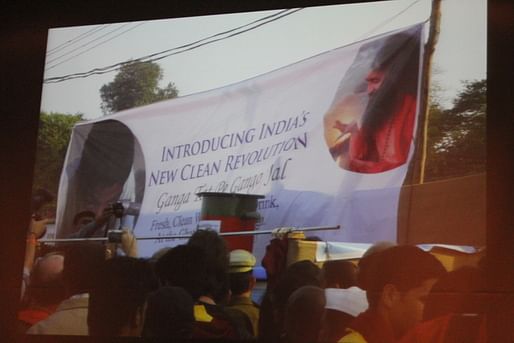

Some of the groups have a political purpose; there's one which has a green mission and the leader of that group met with mayors from up and down the Ganges to discuss pollution and cleaning the river.

7:10: Rahul introduces the students who will present some topics in greater detail: Oscar Malaspina, Felipe Vera, James Whitten, Vineet Diwadkar, and Alykhan Mohamed.

FV: "Once a year, the Ganga (Ganges) retreats, and lets you sit on her lap."

AM: "Like any city, the Kumh is subject to" national, regional, and local politics. Alykhan is describing the complex layers of government that are involved in setting up the infrastructure for the Kumbh, together with the Mela Adhikari, a role that evoled since 1870 when a police officer was hired to help ensure order.

"One of the aspects that surprised us the most was how few stalls and street vendors we encountered. How does this temporal city provide sustenance for millions of residents and visitors?"

Each Akhara (sector) has its own organization, largely of volunteers, to purchase vegetables to local farms, to aggregate the small amounts of food that individual pilgrims bring, and prepare food in a communal kitchen.

JW: The Kumbh's grid is a tool for oragnizing space and rationalising infrastrucutre...on shifting and unstable ground. What is unique about the Kumbh's grid is its ability to balance the government's needs as well as those of the millions of residents and visitors. It is elastic rather than formal; as an abstract tool, the grid allows for the organization of the Kumbh to begin before the form and quantity of land to be revealed by the retreating Ganges is known. The grid is connected across the river by many small bridges, a more flexible strategy than relying on fewer, larger ones.

VD: A more permanent infrastructure for the Kumbh would "would devastate the perceived sanctity and tactility of a landscape that is so fundamental to religious immersion rituals." The pontoons are 2.5m in diameter and create a resilient road surface that traverses the challenging (and shifting) sections across the river and through the mud. The pontoons were welded in November, rolled into place in December, and covered over by wood and metal plates. "Throughout the Kumbh, laborers were constantly and economically replenishing infrastructural capacity ad hoc: re-surfacing rutted-out sand roads with layers of bundled grass, replacing sagging sand bags along bathing ghats, compacting filled toilet pits with matrices of bamboo and grass screens."

OM: For us, the Kumbh "is not about the spectacle of the architecture...but the ability to manage a city in an elastic manner. It's also an example of urbanism driven not by the needs of capital but by other (human) needs. The aim is to understand the Kumbh "as a collaborative anticipatory practice...we are currently looking at other models, such as refugee camps, festivals," and other ephemeral urban phenomena.

7:50: Rahul introduces Gregg Greenough from the School of Public Health.

GG: The Kumbh Mela compared with the Burning man, in spatial extent and population. The Kumbh is a few times' the spatial extent of the Burning Man, but 1000 times its extent in numbers of people.

GG: The Kumbh Mela compared with the Burning man, in spatial extent and population. The Kumbh is a few times' the spatial extent of the Burning Man, but 1000 times its extent in numbers of people.

GG notes that some pilgrims take the holy water of the Ganges into their mouths, which had implications for their thinking on public health...

GG: The British, by using raiway receipts, were able to determine the numbers of people who had come and gone to the Kumbh."How do you plan something like numbers of toilets for a number of people that you're not sure of--between 30 and 80 million people?"

There were communal, gender-separate pit latrines at the Kumbh; about 30 000 of them. The pilgrims are largely rural and poor, and often don't have the use of a latrine at home. The Kumbh has 165km of roads, as well as 165 km of water supply. Standing water is also a concern.

In terms of public health, the issues include the fact that people are coming from all different regions, with diseases that are endemic to those areas; and the area is cold and in a valley, with people being exposed to fires and a substantial amount of smoke. DDT is used to try to prevent malaria. There are public employees who hold a "pooer scooper" in one hand, and a basket of lime in the other; they scoop the results of open defecation off the street and scatter some lime on the spot, which helps to disinfect and cover the smell.

The public health researchers sampled water from a number of sites and grew the samples (in an egg incubator) to determine E. coli counts in the water. E. coli counts were highest around bathing days (when the temporary population at the Kumbh is highest as pilgrims converge), and rates of diarrhea cases at the Kumbh hospitals was also highest during those periods.

Satchit Balsari: The aim was to determine if disease was breaking out. "Easier said than done." The original plan was to sit at the hospitals and count the rates of diseases that were coming in. But the physicians were seeing a thousand patients each shift, so hardly had time to fill out their registers. One simple innovation was to create columns (vertical ruled lines drawn in pen) in the paper registers, so that the physicans would fill in all of the kinds of data (i.e. every column in their form) for each patient.

What they found was that there was an extreme disparity in patients--around 3/4 of the patients were male--and a disparity in the numbers of cases at each clinic. They also found that the vast majority of complaints were extremely simple--upper respiratory problems, for example--that could have been treated without a physician.

"These are the widest roads you'll see in India," and this is part of the efforts to mitigate and prevent stampedes. There were two stampedes at the same time, for example, and an ambulance took 7 hours to get to the scene. SB is showing images and videos of the crowds that make it clear why stampedes take place: enormous crowds, shoudler to shoulder.

There's a final presentation from Tarun Khanna from the Business School.

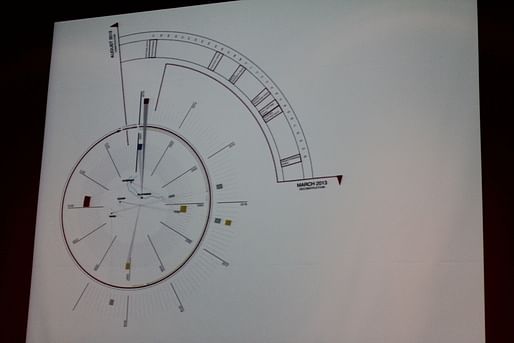

8:22: TK: There were three types of studies that were launched. One was a discussion of how order comes out of what we might expect to be disorder. Another had to do with the emergence of markets, and how information flows to facilitate markets. So we had people taking down the prices of various goods at locations throughout the Kumbh. The third kind of project--Big Data--is in process with negotiations underway to have data transferred from one of the major cellphone providors. 50 to 60% of participants at the Kumbh have cell phones, so they are essentially carrying sensors with a range of data. There are a range of legal, political, and social issues involved in transferring this data outside of India, which would be unprecedneted; as well as technological challenges involved in maintaining privacy once the data is aggregated, and in even being able to manipulate such large data sets. Google, Cisco, and others are interested in this project for the technical challenges and opportunities it presents.

End. Whew!

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

4 Comments

how many got killed this year? It seems like there are stampedes there every year xD

awesome i never witness the live-blog live it seems...

Did not get a number on stampede deaths this year...

This is really interesting. As is the fact that this has so few comments.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.