Hi Archinect!

I’m at the very beautiful Cambridge Public Library (by William Rawn Associates) for a conversation between Marikka Trotter (co-editor with Esther Choi of Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else) and K. Michael Hays, who was co-author together with Trotter of “Reenchanting Architecture” in that book.

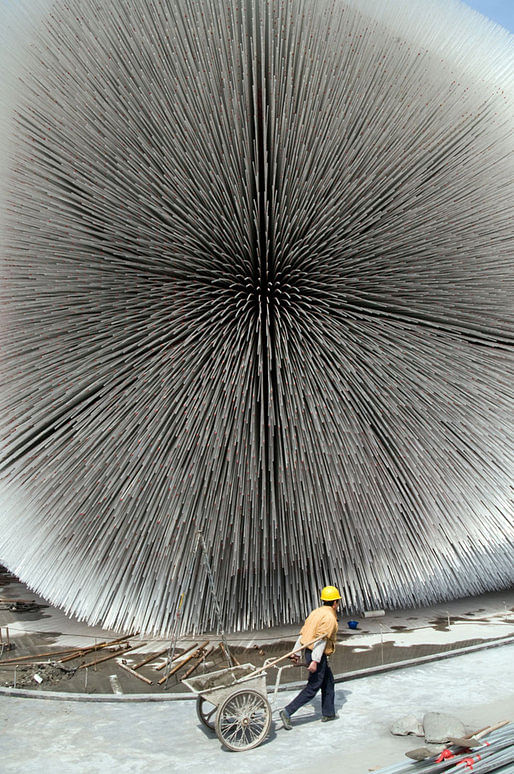

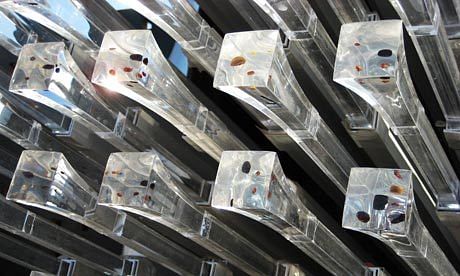

[Note: these are not the exact images shown, but there was a continuous slideshow of these projects during the talk.]

7:15: MT opens by passing the ball to KMH, asking him to talk about the launch of assemblage, since that was an inspiration for her series with Esther Choi.

KMH: Things really have changed since the 1970s and 1980s. During that time, the great teachers were all practicing architects who had little work during the recession, and then become increasingly involved in academia and teaching. Their roots were in practice and were very informed by structuralism (Claude Lévi-Strauss).

Race civil rights in America preceded conversations about gender, sexuality, class, and so on: their theoretical tool was French post-structuralism. So the big switch from Oppositions to assemblage was a switch from a conversation about the ‘folding and unfolding of form’ (Eisenman), to ‘folding form out into its various contexts.’

MT: What were the consequences of folding form out into its larger field—into conversations of sexuality, gender, race, class, and so on?

KMH: Although you could do shelter for the homeless or for low-income people, we didn’t see that as architecture; architecture had more to do with how you could start to frame wider issues in architectural terms. Today, it’s hard for us to swallow the notion that a work of art or architecture has its own politics, independent of the politics of its creator—the artist or the patron.

MT: To the extent that there are things particular to architecture as a discipline, that architecture can do that other things can’t do, Habermas suggests, then architecture can have agency. Are you talking about a disciplinary project of this kind?

KMH: Part of this is a deep respect for the history of the discipline—not just as a resource for ideas, but as a way of rethinking the present.

MT: Would you say that assemblage founded modern architectural theory?

KMH: Theory has always been its own world. But the much-discussed split between architectural theory and practice, in the 1990s, that can be largely blamed on assemblage and its group. Assemblage was never interested in creating a theory that could be instrumentalized. Although we did publish projects—we were the first to publish Herzog and de Meuron in North America, for example.

MT: When you chose the title assemblage, there was a thinking behind that, and a possibility of operativity, isn’t there?

KMH: And then there’s that thing we never talked about: post-Modernism. What we thought was happening was that the structuralism and semiotics of theories before us had a direct lineage with the building boom of the 1980s and with post-modernism. We wanted to stand against that, which mean that theory was the avant-garde for us and that practice had lost its way.

MT: So once money started coming back in for people to practice, the work of these practitioners had taken on a different meaning.

KMH: Even people we respected a great deal—Aldo Rossi and so on—when they practiced, we thought the work was very conventional.

Assemblage for us also related to the collage-like nature of combining many different kinds of writing and argumentation within a journal.

MT: When Peter Sloterdijk visited the GSD, he said that the worst thing about the generation of young people today is that they feel they have nothing to do. That the generation before them “did everything” and left our current generation no room to manoeuver. It really struck a nerve with the students in the room that day.

So in our generation, we feel that the world is incredibly unjust, and that there isn’t room to establish the kind of discourse that we want to have. So we have to go about making that.

KMH: And how did you do that?

MT: Ha! Well we didn’t know what we were doing, which was a benefit.

KMH: What struck me about the first issue is how many interviews there were in the first issue [of Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else] that were raw and unedited—we’re used to interviews being highly produced and edited for publication. One of the things you caught there was a sense that there was a sense of emergence, of something happening that we don’t yet have all worked out.

MT: It’s funny, because as editors you mostly send a publication out into the world and there’s a deafening silence; and you have no idea how it’s been received. Eventually you start to get a few pieces of feedback, and you hope that they are representative of how people felt about it.

KMH: Part of what we started with in this interview was that schools had completely given themselves over to building performance, mood, affect, and atmosphere, and that form was no longer a concern. The other thing was a kind of presentism—that there is no sense of a past that is consequent or in any way binding on current practice. There is simply practice at this moment, and no sense of a future. So there’s no sense of our present as a past-for-some-future, which is a problem.

KMH: Part of what we started with in this interview was that schools had completely given themselves over to building performance, mood, affect, and atmosphere, and that form was no longer a concern. The other thing was a kind of presentism—that there is no sense of a past that is consequent or in any way binding on current practice. There is simply practice at this moment, and no sense of a future. So there’s no sense of our present as a past-for-some-future, which is a problem.

Another problem is that there’s a purely affirmational attitude—a sense that uncertainty can have a use, or a sense that you can do things that you can’t justify. This is a kind of “negative thinking” (in Adorno’s sense) in the sense that there are possibilities at any given moment that are not yet representable—that you can’t yet affirm—and that we have to represent the unrepresentable in a sense. That’s the Kantian sublime—representing the unrepresentable.

MT: The way I could grasp this was that we can—even if we can’t consider how to get there—we can still imagine the hole that a certain thing would make in space.

KMH: The point of the night, if there is one, is that discourse can have a kind of power, predictability, and consequence that is difficult to imagine belonging to something like discourse.

We were thinking about this question: Can there be a contemporary avant-garde?

MT: If we hadn’t looked at specific contemporary architecture projects, we would never have gotten to the contemporary, because you’re not interested in the contemporary.

KMH: Whoa, you gotta be careful there, girl. Well, there was nothing about contemporary practice challenging in the way that I found Mies and Hilberseimer helpful in order to think about architecture. But Marikka kept bringing contemporary work to the table—much of it pavilions and small pieces—which started to make sense within a global project.

MT: There’s a relation to Borges’ idea of an encyclopaedia: that you could make an encyclopaedia of fictitious things, and eventually they’d start to make their way into the world as people took in the ideas. There’s something about architecture that always makes other possibilities possible—it’s not necessarily about knowing where those possibilities are going to go. And this architecture doesn’t have to be something that is built, as long as it goes into cultural circulation.

KMH: Marikka introduced the notion of enchantment as a “singing into being,” of inviting possibilities.

Questions.

It’s pretty quiet, so I ask how they see a distinction between architecture and other practices and fields, given that there are many practices and fields (such as technology) that also open up future possibilities.

KMH: In our world of big urgencies—global hunger, poverty, a real threat of ecological disaster—there are certain things that we can’t address architecturally. Architecture doesn’t seem like the right, to me—

MT: Well, here I have an advantage, because I’m finishing another book called Architecture is All Over, which asks what architecture can do in the face of these dire situations. On the one hand, it looks like there is nothing architecture can do, but on the other it seems like there isn’t anything it can’t do—that the skill set of an architect can’t deal with.

Me again: But is that circular then, if we say that something is architecture if it’s done by an architect, with the skills of an architect? Doesn’t that just displace the definition rather than aswer it?

MT: I’m OK with that. I don’t think there’s anything particular or unique about architecture among other design disciplines; I think they’re all equally potent.

KMH: Hannes Meyer said that architects are specialists in generalization, that architects contextualize problems in a larger and larger way. Whereas biologists and economists work in a fairly small context, their interests come together under a rubric that we can call architecture or design more generally.

Another student comment about the problem with representational tools today, that it is too precise and doesn’t leave enough possibilities hanging in the balance. General consensus that there isn’t enough “smudginess” today. KMH talks about Diller + Scofidio’s Blur Building, and how this project which aimed to resist representation ended becoming an icon; the ridiculousness of trying to make a design of a chocolate bar that would look like the Blur Building.

I still believe in art. Why do we listen to music? Music gives me—and I’m being too personal here, but it gives me something that my mother called faith.

Bill Saunders: There’s a difference between mystery and vagueness. The cop out is that you can get a little more precise than blur; you can look at the graduation exhibition of GSD student projects and get a sense of some kind of direction being established that isn’t literalistic but that is about emerging forms. But what are they? Is there something emerging other than vagueness? This (Thomas Heatherwick’s UK Pavilion for the Shanghai Expo) is pretty vague.

KMH: The Blur Building was primarily critical, and I think there’s a place for that. When we look at, for example, “informal” settlements in Mumbai, Rahul Mehrotra would never call that informal because he can see the form, the order in what we see as chaotic.

MT: I think we’re still in a process of trying to figure out what we’re seeing. (Reference to Heatherwick’s UK Pavilion—it looks vague but it is articulated; each rod is a seed capsule and comes to a point).

KMH: This for me is the healthy thing about the relation between theory and practice now, as opposed to the assemblage or Oppositions years. There’s a productive division of labor. I struggled to write the piece for Nader Tehrani’s project at Georgia Tech.

Question from student: What kind of studio would you teach?

MT: In the studio I taught recently, I assigned one reading from Deleuze, and we looked at one site for the whole semester--it was not a site that was particularly useful for anything and the project was to find what kind of latencies it held.

Question from audience: In practice, where you have a definite site and program, why is there still a vagueness in form?

KMH: There are different kinds of architectural practices. These are the more speculative projects that we were looking at tonight; with the exception of the UK Pavilion, they didn't even have a program. So this isn't a way to build a public library, but as a kind of research it will eventually impact how we build a library.

KMH: The ICA is very generic, it's nothing like the Blur building. It's not like it looks like Blur, but it's learning from Blur.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.