Hello Archinect!

Here we are in Piper for more blah blah blah. This, the second volume of the Eclipse of Beauty symposia, features Evan Douglis, the Dean of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and Georges Teyssot, a professor from Laval University's school of architecture in Quebec City. And it is called "Taste."

6:37 pm: Scott is at the podium. He's equating Kant's "universal subjective" with Deleuze's "affect," and discussing how "taste is associated with elitism, if not authoritarianism." [At this, Dean Mostafavi smiled and cleared his throat.]

"The implicit relativism creates a situation in which all judgments are supposed to be equally valid and therefore beyond dispute. ...There is a necessary correlation between the absence of judgments of taste and a smoothly functioning market. Paradoxically, though, it has to be people like Gehry, Koolhaas, and the ecological movement that has helped dominate the difficult matter of taste coming out of the academy to a general audience."

"The pure relativism that we are in now has abolished the solid ground against which to mount a critique; we have a situation in which we have erased what Kant would have called "common sense," that is, the sense of taste that we all hold in common. Everything is disparate and in this unmitigated relativism everything tends to be flattened."

6:42 pm: Introducing Georges Teyssot. General glowing comments, then: "...the way we think about the threshold, which, actually, is personally an obsession of mine--but only in design."

6:44 pm: Georges Teyssot: "...I am satisfied with the fact that I had to work very hard for this evening, because it has forced me to come back to some reading that I hadn't done in a very long time."

He's taking us back to William Hogarth's 1753 "The Analysis of Beauty," and particularly, to the "line of beauty" and the platform of "variety," which were for Hogarth the primary elements of beauty. Hogarth wrote: "And the serpentine line, by its waving and winding... [is a]...line of grace."

Hogarth again: "Few angular objects are entirely angular. But I think those which approach the most nearly to it, are the ugliest." "If you have tried how smooth globular bodies, as marbles...have affected the touch when they are rolled backward and forward... you will easily conceive how sweetness affects taste."

"And here we have dear old Kant. Oh my God, I have not read Kant in so many years, and how it is you can't imagine. Don't try it. The proportion of pain and pleasure is not a good one." [Chuckles. Seriously, where is K. Michael Hays when you need him?]

Kant wrote: "Beauty is the form of finality in an object, so far as perceived in it apart from the representation of an end." Teyssot: "What does that mean? And Kant changes this as he goes through. ...he will introduce the concept of genius in the fine arts."

Teyssot is explaining how for Kant, genius is about production and taste is about reception; by the end of Kant's book, he has shifted this to associate genius with content and the imagination, and taste with education. One twist: Kant describes how there can be a beautiful representation of the ugly, as in a painting of a massacre. But for Kant, "There is only one kind of ugly that cannot be represented (and remain in accordance with aesthetics), that is, disgust."

Now we're on Karl Rosenkranz' Aesthetic of Ugliness which was among the earliest writings on the philosophy of ugliness, and "draws an analogy between ugliness and moral evil."

[I should note that Teyssot doesn't have a laptop at the podium; apparently they had a technical SNAFU and the slides are being projected from the control room at the back. So throughout the lecture, Teyssot has been maneuvering the podium forwards and turning it to face the screen, so that he can read and refer to his slides. He's standing almost directly beside me now, as I'm sitting in the second row.]

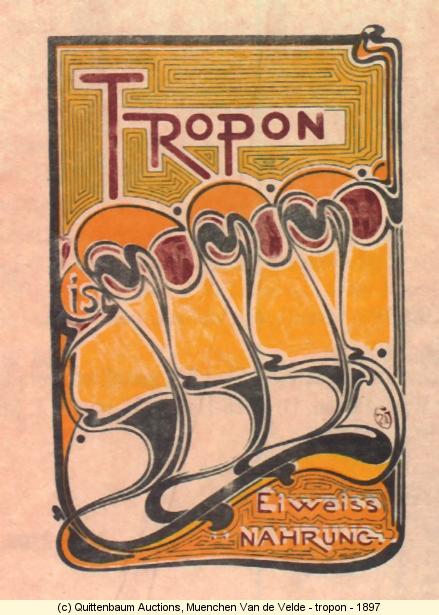

The above slide is Henry Van de Velde's advertisement for a company called "Tropon," and Teyssot is saying "the line is the force," in a Darth Vader voice.

Now we're on Siegfried Giedieon, Mechanization Takes Command.

Now it's Banham's Topology: Banham: "As a discipline of architecture typology has always been present in a subordinate and unrecognized way." (What does Banham mean by typology? Teyssot refers to Louis Kahn's Richard Medical Building, and Marco Zanuso's Olivetti Factory in Argentina.)

And now Gilles Deleuze's "A Typology of the Living": "But membranes are no less important, for they carry potentials and regenerate polarities. They place internal and external spaces into contact without regard to distance. The internal and external, depth and height, have biological value only through this topological surface of contact."

And Deleuze cites Gilbert Simondon: "The characteristic polarity of life is at the level of the membrane; it is here that life exists in an essential manner, as an aspect of a dynamic topology… The entire content of internal space is topologically in contact with the content of external space at the limits of the living; there is, in fact, no distance in topology; the entire mass of living matter contained in the internal space is actively present to the external world at the limit of the living… To belong to interiority does not mean only to ‘be inside,’ but to be on the ‘in-side’ of the limit… At the level of the polarized membrane, internal past and external future face one another."

Teyssot: "Another example of individuation in Simondon is crystallization. ...The process of individuation occurs...between each crystal and the contiguous amorphous substance. Simondon argues that the simple model of crystallization may be used to understand the process of individuation through physical and biological systems. One perceives distinctions between matter and form, organism and environment, species and individual--but these are merely manifestations of simple processes..."

"In conclusion, in my opinion there are two possibilities for architecture today. Either a proces of crystallization (Ogiati's visitor's center in Switzerland), or--and I don't know yet if these are opposite--Jürgen Mayer's project in Seville."

"These projects propose that we think again about the line. After all, we have to learn to live on a spline. it is difficult to live on a spline. Can we inhabit the complexity of a nerve?"

7:15: Scott's introduction of Evan Douglis: "I daresay he is inventing a new type of ornament, so extreme is its originality and the refinement of his forms and surfaces. There are no lines here to speak of. And he differs very strongly from other digital works in the field, in the sense of this quality that I'm trying to describe but cannot."

Evan Douglis: On the impossibility of rendering beauty (and its opposite) into language: "...I'm reminded of Elaine Scarry's...[reading of] the impossibility of relaying one's physical suffering to another through words. Both beauty and pain, at opposite ends of human existence, expose the surprising limits of language to adequately provide insight onto the cognitive and sentient experience from these often misunderstood domains."

"I'd like to propose an alternative frame to reassess...the iconography of desire in the reading of architecture. This will be based on the five performative categories:

1. disagreeable beauty.

Daniel Lee's "Manimals."

Andres Serrano's "Piss Christ."

2. uncanny incongruities.

M. C. Escher's "Double Planetoid."

"With the arrival of computation, an even greater degree of iconographic smoothing is available, for an image to sustain an even higher level of uncanny unbelievability."

3. animate flesh.

"Preoccupying the imagination of countless civilizations is the dream of synthetic immortality where the material world that surrounds us obtains an air of excitability..."

4. erotic desiring machines.

"One could conceivably reconceptualize architecture with the right underlying effects in place as a series of perpetual designs, imagined as a serial of triggers. ...M. C. Escher and Hans Bellmer curiously share a vision of a world that perpetuates the illusion of infinity and erotic surprise."

5. dazzle topology

Definitions done. As with Teyssot's presentation, Douglis laid out a sequence of ideas without really weaving them into a strong overarching argument (or if he did, it was too subtle for me). But Douglis has now switched to showing his own work; maybe we'll get his thesis here.

"REptile," for a restaurant in Japan.

"Like most of the work there is an explicit attempt to ahve the surface acquire a certain kind of animate sensibility."

"Floraflex."

"Depending on where you stand in relation to the surface it will either become transparent or opaque. ...All of this was computationally driven, so there's a massive archive of options available...in modifying effects."

"Infinity Nets."

"This is a prototype for a column that would be extended into a freestanding building."

"Moon Jelly" for a restaurant.

"There is a new modular element that is entirely flat but increases the level of complexity of the ornament across the surface." The openings accommodate lighting and other things that have to come out of the ceiling.

OK, he's done. Now the discussion.

Antoine Picon: "There were a lot of connections [between the two talks]: the body, there was a bit of prosthetics, some kind of neo-sadistic touch on suffering. The line between taste and suffering, pain and pleasure."

"First, Teyssot: I wanted to ask you why you choose that--do you really have a problem with taste as superficial? And what about the connection between taste and the body; that came through strongly. Who is the subject: is it the generic individual or someone else? I was disappointed not to see French 18th century taste, but something more like emergence, something that might be published today in a book on digital architecture."

"Now, Evan: "And here, I found a lot of 18th century stuff, you know: bizarre punishment. I had the impression of being in a Marquis de Sade novel; I appreciated that. Then there were a number of 19th century things, like impulse, and I was reminded of the criminal ornament of Lombroso. The idea that there is something a bit dirty in the pleasure we have from ornament. But...is there something like bad taste? I was expecting that there would be bad taste, and unfortunately you presented very beautiful stuff. You spoke a lot about the ugly, but we didn't get the ugly or bad taste."

"To conclude these remarks. I'm disappointed by how serious we are in the end. In the 18th century France, it was such a drama to think that taste could be social. So my question to both would be about inventing a true superficiality, a taste that comes from bad education, prejudice, all the things we try to exclude from architecture."

Teyssot: "..As soon as you say good or bad taste... either you go to Diderot and the public and the salon; and the question of education. Education can be either of the public or of the artist. The guy who knew about that was Kant, but..."

Picon: "We've been too long in academia to really appreciate education."

Teyssot: "I would like to bring good taste and bad taste back to today's matter. I thought it would be interesting to know what the Spanish think about Metropol Parasol. It turns out that the whole profession there hates it and takes it as a matter of personal offense."

Douglis: "You raised the question of morality, and of limit and the question of ethos. Is there a boundary of that production that would produce a kind of inverted entropy? And then you spoke of a kind of darkness in the presentation. Maybe I'll respond about academia, and the practice where there's an enormous amount of complexity that is made available with the computer, and rather difficult to assert or distinguish oneself. And I'll take it as a compliment what Scott said--I can't be objective enough to know exactly what those terms are. But it seems that it is apropos to raise the question of aesthetics at a time when there is such a multiplicity of variation that is available."

"...For students, it's a provocation to all of you to look at the production of your work simultaneously with the choice of affects in relation to the thesis that is intended as it goes out into the world. You may be the authors, but there are different orbits in which your work will be received, and each has its own bias. It was interesting to hear Georges' presentation, to think of the kind of obsessions that" come and go, like the idea of genius."

"And you said I didn't show anything ugly. That word is difficult. I'd like to think that we're talking about degrees of difficulty, that work has a problematic condition built into it--some more familiar and domesticated, so there's a deep latency of meaning, and at another time maybe..."

"For me, it's strangely perverse that a line can be encoded with an ethic. And today, when so many lines are required to underlie a complex surface, it would be impossible to cut a section or plan and say that a single projection has a single, specific agenda to it."

And now just to cherry-pick a bit of Schumacher-bashing in the conversation:

Picon: "Oh, and Schumacher's book is out. It arrived in the Rensselaer studios."

Douglis: "Yes, he already sent an email asking what we think of it."

...Teyssot:"And there was a horrible article, by Patrick Schumacher I think [the "I think" was entirely ironic here], saying that the parametric is a style, and he is the big holder of that style, and no one else. By the way, if I were an architect I would be really angry about that."

Question from the audience: "As a student, we see that each school has a system, a kind of consensus of what is generally found to be aesthetically pleasing. But I'm curious, as are several academics, why academia on the whole has not been effectual in the classification of taste and beauty?"

Douglis: "Hm, I see that Mohsen moved, and so did Scott."

Picon: "We should ask Scott."

Douglis: "Certainly all schools construct a culture, and I'm hesitant to generalize about that, but I do think that the differences among schools are a good thing. It's the responsibility of the leadership of the school to put together a heterogeneous model so that there is no uniformity, and the tension and aggregation between different schools of thought is seen as a positive thing that could produce a third condition. I would be very uncomfortable describing schools in terms of style and taste and aesthetics. I'd prefer to talk about a series of cultural projects. Whether it resides in a book, or in specific practices--analog or digital--or if it foregrounds all the dilemmas with environment."

"I'm not suggesting that aesthetics isn't a deep challenge historically within our profession. In the 1980s I taught at Cooper and Columbia; you couldn't find two more opposed institutitions. But uptown they had acquired MAYA, coming out of the automobile industry and Hollywood, and we'd be sitting with Bernard and Frampton and I remember, besides the enormous excitement, was the difficulty we had in speaking about it. It took a number of years for these critics--and they're quite brilliant--to be able to construct the appropriate nomenclature. I couldn't stand it then, and can't now. And that's why I haven't read Patrik's book, although I'm sure it's well intended. But I'm very uncomfortable, as with deconstruction, with these cultural shrouds: they wrap up research, not open it up.

"I think this is still a struggle. I love the computer, but its astonishing to me how many students lose their ability to author their product, and it's the software with a predisposition to privilege certain effects that dominate; and it requires a forceful and critical guide (here I mean the teacher or the institution) to help them to be able to evaluate these tools in a critical way."

Question from Ingeborg Rocker about to what extent algorithmic work can be critical:

Douglis: "...I'm always trying to move those questions out into the physical world and assess their haptic consequences. I've always thought the most amazing architecture is wonderfully erotic, and it doesn't have to necessarily look erotic, but ultimately it has to do with a kind of psychological stance, and maybe a disquieting relation to the work that captivates the audience and keeps them interested in the most curious way."

8:20 pm. Arright, that's it. It was a bit disjointed tonight--but there you have it.

Thanks for reading!

Lian

This blog was most active from 2009-2013. Writing about my experiences and life at Harvard GSD started out as a way for me to process my experiences as an M.Arch.I student, and evolved into a record of the intellectual and cultural life of the Cambridge architecture (and to a lesser extent, design/technology) community, through live-blogs. These days, I work as a data storyteller (and blogger at Littldata.com) in San Francisco, and still post here once in a while.

2 Comments

great stuff as usual -

sounds like the lectures are getting good over there...

culture is something you wave to on the way to the bank.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.