The perils of the text infiltrate the spaces of the city. And somewhere between the experience and the perception of a text, Roland Barthes suggests the primacy of pleassure. For him, the text is an object to be consumed, and text-consumption is within the province of the reader or critic. The reader or critic does not rewrite a text; rather, he or she completes it by adding those final touches that help disseminate the text and help ensconce it firmly in popular (collective) memory. If we are to interpret the city then as a text, then a sampling of works by Bernard Tschumi, the Situationist par excellence Guy Debord, as well as Denis Hollier's interpretations of George Bataille's writings will serve as guides for navigating and consuming the text of the city.

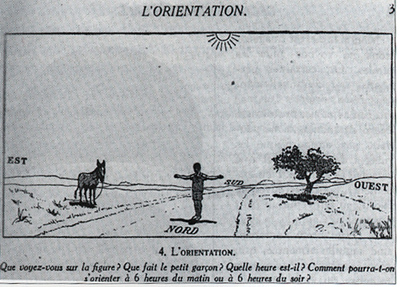

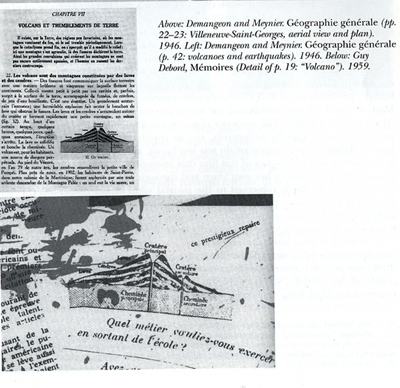

And how, exactly, do we do this? In the most recent issue of October, Cooper Union dean Anthony Vidler describes Situationist space as wholly derived from Guy Debord's childhood ephemera. In "Terrés Inconnues: Cartographies of a Landscape to be Invented," Vidler demonstrates how an elementary school geography text, Albert Demangeon's and André Meynier's Géographie Generale: Clase de 6éme is Debord's own proto-Situationist text to the city.

Through various diagrams, plans, and aerial photographs of world cities that act as "objects of memory, reflection, and strategic plan," Debord used the Géographie Generale as a guide for manuvering through the complex conurbations of the contemporary city.

Debord even cut out and grafted images from the text onto his own Situationist maps. A childhood text literally maps the terrain of the Debordian dérive.

Yet the grafting of a text onto a city can be a subtler enterprise -- with devastating results. In Jorge Luis Borges' short fiction Death and The Compass, Löhnrot, a police investigator, uses clues from the Torah to pinpoint the exact geographical location of an upcoming murder. Detailing an exchange between Löhnrot and the criminal mastermind Scharlach, Borges writes:

"I know of a Greek labyrinth that is but one straight line, So many philosophies have been lost upon that line that a mere detective might be pardoned if he became lost as well. When you hunt me down in another avatar of our lives, Scharlach, I suggest you fake (or commit) one crime at A, a second crime at B, eight kilometers from A, then a third crime at C, four kilometers from A and B and half-way between them. Then wait for me at D, two kilometers from A and C, once again halfway between them. Kill me at D, as you are about to kill me a Triste-Le-Roy."

"The next time I kill you," Scharlach replied, "I promise you the labyrinth that consists of a single straight line that is invisible and endless."

When grafted onto the urban space of Borges' story, the above passage describes a rhombus formed by two equilateral triangles.

The shape forms a literal tetragrammaton. the Hebrew word for God (JHVH), that is superimposed on the city. And in order to decode the tetragrammaton, Löhnrot had to complete his very own psychogepgraphic dérive throught the city. The fact that it is a tetragrammaton that Löhnrot is completing is signifcant, as the final utterance and completion of the forsaken word is what literally spells out Löhnrot's demise

to be continued ....

3 Comments

But what about Denis Holliers Against Architecture? I couldn't get through it, I have to confess - and I have read my Bataille. what insights did you gather from Holliers book?

Hollier's book is weird, man. It's not really about Bataille, is it? The book was famous for reprinting Bataille's first ever article, his lament for the Church at Notre Dame de Rheims. The book reads like a bunch of crib sheets regarding Bataille's more architecturally-inspired work.

The English version of the book is famous for its introduction, where Hollier excoriates Tschumi for ripping Bataille off.

I think using Bataille for architecture writing is problematic ... Hollier's book attmepts to do it, but man, I don't get it either.

Yeah. damn. Anyway - the Tschumi thing is pretty correct - I was surprised after leafing through architecture of disjunction (or whatever it is) and noticing how Tschumi doesn't seem to aknowledge his debt to Bataille - he just mentions him in passing, while his take on architecture seems to stem very much from a "Bataillean" attitude - that can be also linked to foucaults heterotopias and whatnot. I'm sure Tschumi has read Bataille extensively.

Holliers book hovers between being somewhat biographical and then purely "inside" Batailles thinking. that just screwed me up. Have to have another go sometime - anyone here that can say they got it?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.