Aug '08 - Dec '10

Halfway over already!?^

Our task was to design a small pod for a climatologist to spend 12 hours observing, resting, eating, and recording. A bathroom had to be included as well.

We were to base our designs on the dimensions of our own bodies, and discover the "volumetric differential between claustrophobic and efficient."

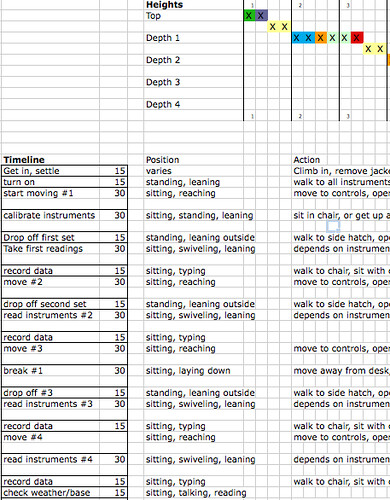

We wrote a script for our climatologists, which yielded our bodies' spatial needs. With a size limit 2.5 times the size of our individual bodies, we then set to designing our pods.

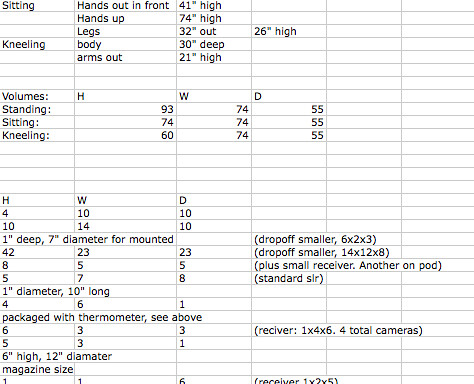

Right from the start I got all hung up in hard information- Not just my own dimensions, but dimensions of meteorological equipment and what activities a climatologist would do over 12 hours. For a while I couldn't think of anything visual or spatial- just numbers, letters, spreadsheets.

What does this all mean?!

Given the choice of rooftop, park or plaza, I opted for the rooftop site, believing that it is the most uniquely urban. City roofs are inhabited much differently than those in the suburbs or countryside.

My own difficulties were mentioned in earlier posts, but I still cannot explain them, to be honest. I was somehow clogged up in my head, and for a while I was just spinning my wheels, making drawings, making models, trying to figure out exactly where I was going.

While I was doing that, everyone else in the class seemed to me plugging away, and I loved the variety and creativity in the projects.

There were climatologist pods that:

-became submarines,

-went undercover as lunch trucks,

-were built by a climatologist with multiple-personality disorder,

-used algae to regenerate water and oxygen,

-were carved underground,

-were modular and adaptable to any individual,

-attached right to the body,

-totally shut out the natural world,

-harvested rainwater,

-I heard there was even one made out of eggs.

I hung my roof pod off the side of the building, like a window washing platform, able to travel up and down vertically taking different measurements pertinent to city environments, such as air particulates, reflectivity and after-dark heat transfer.

In the end I did indeed have a pod, but due to my treading water my own work became more about process than product. I never did get to install that bathroom for my climatologist, but more importantly I discovered a lot about the way I work and how the architectural process plays out.

To get past my stumbles I concentrated on sectional drawings, and threw out all the information about gear dimensions, power, winch speeds and whatnot.

More than anything I had to locate and inhabit the balance between possibility and reality. As this is school (and the first semester at that), I had to understand that we are oriented more towards possibility, and are free to make up (or ignore) much of the specific details we need.

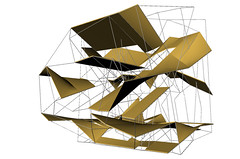

At one point I had a number of drawings that were "pretty" and "interesting" to look at, but I couldn't understand how they would become architecture. After several desk crits that clarified and confused me all at once, I realized there just a week left before the project was due, and told myself I would simply force architecture onto my project, at whatever weird and abstract point it was at.

So, the final week became one of trying to define a space within a given limit. Can't get much more basic than that, but this time the limit was defined by my own earlier work- body dimensions, timelines and sectional studies.

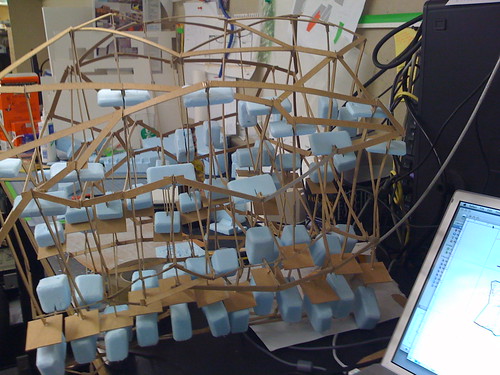

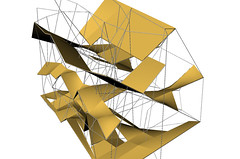

At this point I had this chipboard cage I had been carting around and staring at for about a week. I created it based on several earlier diagrams, but now had to turn it from abstract study to inhabitable space.

Basic, empty cage, about 16" high

The blue foam was supposed to be something, but in the end it was just a dead end.

In the end it became space, but I am still not sure about inhabitable.

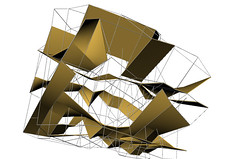

Floors, ceilings, walls, doors- these basic architectural elements all sort of came together in the same elements of my pod. In other words, at one point the surface is a roof, but approached from another way it's a floor.

Front left

Bottom right

Back, from above and right

The one instrument I discovered at the beginning of the project that made the cut and came back in the end was a Stevenson Screen. This is really just a louver that keeps out harsh winds and sunlight but allows humidity, temperature and barometric pressure to reach internal instruments.

I kept this idea of permeability in mind when I made the surfaces that were loosely based on a slat system. I never wanted my climatologist to be separated from the atmosphere, and in the end, in my pod, there is really no escaping it.

Needless to say the last few days before the reviews were hectic, messy and long. People stayed up all night, mountains of trash were generated, food was inhaled, beards were grown. You get the picture.

Did you hear I got a little cut up?

Lots of stumbling around in the dark early morning hours.

I was a bit jealous of the half of the class that had to present on Monday, not only because they finished earlier, but because they could visit all of the later reviews, but in the end, I sure did make good use of those extra 48 hours!

We were all working right up to the minute the review started. Wet glue, misprinted graphics, empty stomachs, whatever.

The critics were varied, but the mood mellowed over time, and pretty much everything they said was true.

Personally, I learned a lot in just a few hours, most importantly, that presentation means just as much as the project itself.

Yeah this is mine:

It felt so refreshing to be done with that project, but I heard so many people say they were excited for the next, which we are now all working on as I type this. It never ends, it just slows a bit now and then, but that's enough have a drink and a party.

3/4 of my studio

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.