On Photography, Poetry, & Post-Oil America

Ruins have traditionally been associated with civilizations of the past. We know them from Europe, The Middle East, Asia, Central- and South America, where they stand as sculptures in the landscape that remind us of these almost forgotten and ancient empires, only now existing in parallel realities of our imagination. They mark the end of a civilization, and they are in that sense post-apocalyptic in relation to those societies. But we rarely think of them in that regard, as we are still here, observing the ruins belonging to a different culture and another reality, watching them from close proximity, or more likely, looking at pictures taken of these petrified monuments.

An unsettling and intriguing thought emerges when Detroit, a major city in “The New World”, starts decaying and literally turns into a city of ruins before our eyes: These ruins are not echoing a civilization from the distant past, but rather, they are foreshadowing / serve as a pre-echo for the downfall of our modern western civilization as we know it.

As Ignasi de Solà-Morales Rubió puts it in his essay ‘Terrain Vague’, our preconceived notions of what the modern metropolis is and should be owes a lot to photography, which as a medium was developed at the same time as the expansion of the great cities. Now, it has become impossible “to separate our understanding of modern architecture from the mediating role that photographers have assumed in this understanding. The manipulation of the objects captured by the camera - framing, composition, and detail - have decisively influenced our perception of the works of architecture photographed.”

Architectural photography holds a major importance to the architectural profession, as most people will never get to experience the great buildings of the world, but they can have the experience of perceiving the buildings through photography. And so, “Architects live and die by the images that are taken of their work”. In the same fashion, for me, the city of Detroit has lived and died by the images I have seen of the abandoned warehouses, factories and skyscrapers.

In architectural photography, the objects of the images that are taken are usually static. As opposed to photography concerning living or moving objects, the element of time is not an immediate factor. Buildings are not in flux in the same way as people, or nature (if you can even separate the two, as that distinction is in fact man-made). But that is not to say that buildings are not changing all the time, because they are - just not as fast. Buildings certainly have an arc, a beginning, middle and an end, but the fact is that the world around the buildings is changing much faster than the buildings themselves, and thus it appears static or permanent, and the change around the object is what becomes the subject.

In architectural construction photography, the documentation consists of a moment in time while the building is being assembled: Never again will the building look like this, and the image provides information about the tectonics and anatomy of the building you would not be able to see otherwise. In this stage the building is still changing relatively fast, and the immediate future of the building is certain: It is being built for a specific function, made to last for a specific period of time, or maybe in the hopes and dreams of the project developer, made to last forever. Paradoxically, this endlessness of function also suggests an ending for the arc of the building, because if nothing changes there is no reason to continue the documentation - but of course this is not reality as nothing truly lasts; building a building in the hope of infinite permanence is a day dream conjured up by mankind's inability to look beyond our own lives.

So if the construction photography documents a moment in time that will never come back, can the reverse be said about disassembled building photography?: Are these images hinting at a time that has yet to come? Just as in the construction photography, this exact moment in time will of course never come back, but contrary to the construction photographs, these buildings have a very uncertain future. In these photographs of Detroit by Andrew Moore, the buildings stand disassembled, abandoned and stripped of their original function. Empty shells awaiting their destiny either as empty lots or reused, redefined and reincarnated as something entirely different. No one knows as what, when or even if that will happen.

In the case of The Michigan Theater (as photographed by Andrew Moore on page 75 in Detroit Disassembled), once a decadent theater with 4050 seats which made it one of the largest in the state of Michigan, now gutted and equipped with three concrete floors functioning as a parking garage serving the suburban commuters that fled from Downtown Detroit over the last 50 years. Built on the site where Henry Ford built his first automobile (or Quadricycle if you will) in 1896, The Michigan Theater, once a glorious monument to the wealth of The Motor City, now stands as a monument to the crisis of the American economic condition. What built it is what killed it. Looking at this case from a hardcore post-critical and capitalistic perspective, one would probably not call the fate of the Michigan Theater a sad one, as clearly, the declining downtown population and multiple bankruptcies of the theater proved that Detroit did in fact not need another theater, but rather, a parking garage serving the offices of the building. In this sense, the The Michigan Building (which the whole complex goes by) has adapted to the condition of the city. It has survived abandonment and (partial) demolition by redefining its function. But while the building is definitely still functional, moving on to a post-post critical stance, that does not mean the building is not dysfunctional. The Michigan Theatre cost the equivalent to 62 million dollars in 2008 to build, and surely, now serving as one of the most expensive parking garages ever built, that is not a very sustainable way to spend our resources.

When I look at these photographs of the empty, dilapidated and disassembled buildings, it reminds me of the fact that after the original function of the building has ceased to exist, the building itself might not, and time will still be passing. They remind me to start to think about the permanence of building and materials when I am designing. What is the lifespan of the program? Materials? Urban condition? For example, when using concrete, one might want to come up with a spatial composition that provides great flexibility for both the imminent program and possible future uses, as concrete is a very permanent material, costly to produce and difficult to disassemble and recycle.

The last century has been characterized by a mass consumer society, where profit and economic gain eclipsed environmental responsibility and any concern for the world we leave behind for future generations, and the firm belief that capitalism would continuously catapult humanity towards ever greater prosperity. The American Dream, where people face hardship and adversary and emerge on the other side more prosperous and successful than the previous generation, has proved to be but a dream, an illusion conjured up by the convergence of the birth of american society and the unprecedented economic and socio-political developments triggered by the industrial revolution...

Detroit and the images that are taken of these modern ruins might just be what will inform this change of mentality. We have seen images of modern ruins before from wars or collapsed societies such as the Soviet Union. But just as with the ruins of ancient civilizations, we are able to look upon these abandoned soviet monuments (another of Andrew Moore’s photography subjects) with alien eyes, they still seem almost surreal to us as they were never part of our western society. The images of a Detroit in ruin hits home in a way that we have never quite experienced before. Many believed that capitalism was at the end of all economic models, but when a major city in modern western civilization turns into a ruin before our eyes, we might start to realize that we need to change if we want our society to last. Like a capitalistic mining venture city, Detroit's economy was pretty much based on a single industry, the automobile industry. But unlike the ghost towns that have come and gone with the gold rush, Detroit was built to last. In just one century, Detroit has gone through an entire life cycle of a civilization. From boomtown to shrinking city, Detroit might be one of the best recent examples of the effects of Space-Time compression. On page 39 in Detroit Disassembled, Andrew Moore has photographed a High School NationalTIME clock that has melted into the surreal. Like Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” the image shows how time has been completely warped, not only in Detroit, but in the rest of the world as well. Technological evolution and economic change happens so fast now that we might only realize what is happening once it has already happened. In the case of Detroit, the city has been shrinking since the 1950’s where the city inhabited nearly 2 million people, and now less than half remain. They built a town that was meant to last, but what no one predicted was that the buildings would outlast the economy and population in such a short time.

Time is not the only thing that has been warped in Detroit. In another photograph on page 19 in Detroit Disassembled, we see an abandoned and dilapidated car plant: Collapsed roof, smashed windows, no people. There is nothing in the picture that tells us about the scale of the building except for the presence of the car tires. Just like in the image of The Michigan Theater, the human scale has been completely displaced, and replaced with the scale of the car.

The car based society gave birth to yet another kind of urban condition: Urban / Suburban sprawl. Over the last 50 years, most of the inhabitants of Detroit moved to the suburbs, a move that has been dubbed “White Flight” due to the demographics of the people that moved. Unlike Detroit, a city that was built to last, the suburbs are “so strange, they built it to change” as Arcade Fire puts it in their concept album “The Suburbs”. The suburbs are made with the scale of the car in mind. In some places, there are no sidewalks. Arcade Fire sings of this displacement of the human scale in a way in which is undoubtedly dysfunctional: “First they built the roads then they built the town / That’s why we’re still driving around and around / and all we see / are kids in buses longing to be free”. Distances have no real meaning in the suburbs when everyone is driving around in cars and buses. The land is so cheap and houses are built so fast that it is easier for real estate developers and store owners to simply buy up new land and abandon their old buildings if they wish to expand. The result is an ever expanding sprawling suburb that leaves behind dead city centers and Wal-Marts: “Sometimes I wonder if the world is so small, that we can never get away from the sprawl / Living in the sprawl, dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains, and there’s no end in sight / I need the darkness someone please cut the lights”. In the song “Deep Blue” they sing of how the times are changing, human culture and technology is repressing and replacing nature, and yet at the same time, technology seems to be approaching humanity as well to replace us. But as earlier stated, can this distinction between nature, humanity and technology even be made, or are they all the same? “Deep Blue” is a reference to the legendary game of chess ‘Kasperov-Deep Blue 1996’ where an artificial intelligence made by IBM, Deep Blue, beat a reigning grand master of chess, Gary Kasperov for the first time. “Hey put the cell phone down for a while, in the night there is something wild, can you hear it breathing? / Hey put the laptop down for a while, in the night there is something wild, I feel it it’s leaving me” He continues, according to the liner notes, singing: “Lala lala lala lala” but in a way that unmistakably sounds like “The lie the lie the lie the lie”...

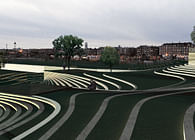

This yearning to get away from the endless sprawl and return to nature is exactly what is happening in Detroit now. In this image from page 49 we see the remnants of the city grid, sprawling as far as the eye can see with very low density. In some blocks, only one or two single-family houses remain. Two huge roads carve through the landscape; they seem vastly over scaled compared to the car congestion, and yet, there is still more cars than people visible in the picture. On the roof, the word ‘EBOLA’ has been written across the parapet brickwork, as if someone had been standing there, looking out over the city and concluded that whatever happened to this city must surely have been from an epidemic of one of the deadliest viruses known to man. And some might argue that was exactly what happened: Capitalism. Racism. Suburbanization. Once the fourth largest city in America, a third of the area of Detroit has returned to empty land. The city centre seems to be returning to a state that can perhaps best be described as landscape rather than as city. While this might be the fall of Detroit, it does not have to be the end of Detroit. After the great fire of 1805 the city adopted the motto, Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus, “We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes.” As people have moved out of Detroit, something else has moved back in: Nature. On page 36 we see an old school book depository with a collapsed roof. From the old, ruined and decaying books, a vibrant birch tree grows towards the light. The message seems almost too obvious: in a world where we can no longer rely on oil to ensure our survival, alternative ways of life are needed, and these car based urban conditions cannot endure. In a single-economy city that has fallen victim to the pitfalls of capitalism and globalization, we could use our knowledge and take advantage of the potential of a near empty city to redefine what it means to live in a modern city, with sustainable local post-capitalistic economies and urban farming.

When most people look at Detroit they see the past. But really, we are looking into the future. Should we allow for these ruins to remain, to stand as monuments and reminders of what can very well happen to our cities, or should we intervene? I guess it depends on your conviction of either post-critical or post-post critical stance. Whatever the case, if Detroit will stay in this ruined state or if it will arise from the ashes as a shining example of a post-capitalistic green city, the photography will remain. Just like the ruins of Rome or Machu Picchu, could we imagine postcards from Detroit sporting a photograph of the abandoned Ford River Rouge complex? The Michigan Theater Parking Garage? In a way, all of these images have already become “money shots” with the amount of photography books and level of interest on the subject matter.

Many architectural competition submissions increasingly revolve around the “money shot” and the designs proposals themselves have also been criticized for being too shallow and relying heavily on the wow-factor of these images. When looking at these “money shots” of Detroit, you start to wonder whether it really matters with a money shot. Sure, they are beautiful and they sell the project. But is it the crucial part of our profession? Maybe from a post-critical stance, but if we want to avoid falling into the same patterns that led us to a Detroit in ruins, maybe we should redefine the money shot and our profession, and turn the camera away from the object, to look at how life is changing in and around the building. After all, that is what truly matters.

- Chris Gotfredsen, 2011/2013

Status: School Project

Location: Seattle, WA, US

My Role: Critical Theory, Writing

Additional Credits: Class Instructor: Nicole Huber, University of Washington

Photo credits: Andrew Moore

Citations and more credits to be added.