When a well-intentioned Alabama teenager tweeted a smiling selfie taken at Auschwitz-Birkenau, she attracted a deluge of hatred and outrage from across the internet. Lambasted as disrespectful, insensitive and inappropriate, the selfie was later explained as a means of memorializing her visit to the camp for her father, who had passed away exactly a year prior to her visit. Her gesture was by no mean the first or last of its kind, and represents an inevitable schism in memorial politics – as traumas recede from lived-past into historical contexts, how should cultural inheritance be balanced against personal experience? And how can this balance be articulated in the memorial space?

Currently, Auschwitz-Birkenau is memorialized in a variety of ways, but the structures themselves are not being actively preserved. In 1947, the Polish government established a memorial to all victims, and opened an exhibition of prisoner paraphernalia at Birkenau in 1955. Auschwitz I, the original death camp, and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the second camp established a few miles away from the original camp, became an UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979, and are currently open to tourism. Birkenau's structures have nearly disappeared: Nazis bombed the crematoria before abandoning the camp, which was then harvested for building materials immediately after the war ended. What remains is in ruin. This status is not currently being officially reconsidered, but as the number of Auschwitz-Birkenau survivors dwindles with time, speculations begin. What on Earth is the decorum for memorializing a place that both demands to be recognized, while denying any sense of closure from that recognition? We might as well memorialize the night sky.

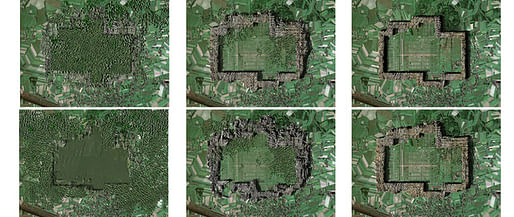

This struggle serves as foundation for Thinking the Future of Auschwitz, a theoretical Graham Foundation-supported proposal for Auschwitz designed by Eric Kahn and Russel Thomsen of IDEA office. Thomsen, in a conversation with Eric Owen Moss at SCI-Arc last Tuesday, described the proposal: "in 2045, which would be 100 years after the liberation of the camp, and after the last survivor has passed of this world, that trees would be cut from the countries in Europe where Jews were deported, proportionally, they'd be brought to the camp, then we would erect this large barrier by stacking the logs around the perimeter of Birkenau. Auschwitz I, the museum, would remain intact, and it would be the place that would record all the facts and it would explain it in a curatorial manner." The logs would be erected high enough to make it impossible to see into the camp from the ground level. Over time, the logs would be allowed to decay, prompting another reconsideration of the site.

"We called it "blanking" the site, because we didn't like the idea of saying we were withholding it, or erasing it, we weren't doing any of those things" explained Thomsen. "You would no longer be going to Birkenau to seek more facts, to seek more understanding, to seek more connection, because you can't find it anyway. But rather, you'd be walking around the perimeter of this thing, and it'd be withheld in some way – fundamentally altering the way you understand it. You'd contemplate not what is it, but why is it. And you can't answer that question." The Tel Olam would also transform the March of the Living, a walk from Auschwitz to Birkenau to commemorate the Nazi's death marches, to include a perambulation of Birkenau.

Why people visit sites historically associated with death, horror or tragedy is, predictably, muddy. Conventional wisdom suggests such "Dark Tourism" is a means of closure, or enhanced understanding of colossal, traumatic events. But if closure were really possible, memorialization would be another means of preservation – a freezing of understanding, delineating a tragedy to ultimately inadequate terms that defy interaction. For Thomsen and Kahn, understanding is akin to forgetting. And forgetting Auschwitz should be impossible; for its victims and significance to be respected, it can't ever be fully understood. To this end, any architectural intervention should remain at a distance, in perpetual contemplation without promise of resolution.

The conceptual foundation of IDEA's proposal is the Tel Olam – in Deuteronomy, a marker for, in IDEA's words, a "place of unspeakable evil, blotting out and rendering a place inaccessible". The logs would literally forbid access and view of the site, while subsuming the reference to humans – the trees being both a barrier to, and the symbolic result of, the atrocities within their bounds. But obscuring the main reference point also elicits the same existential grapplings found in other Holocaust memorializations. Peter Eisenman's Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin immerses and dislocates the visitor amidst cold monoliths, and similarly but more removed, the zig-zag twists of Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum Berlin convey the disorienting crisis of navigating an ethnic history fraught with trials and tragedy.

But Eisenman and Libeskind's structures are not physically located on what is effectively the world's largest Jewish cemetery. Their Holocaust references are just that; empathetic re-interpreations of experiences from actual event. The authenticity of Birkenau is so extreme and horrific, invoking other histories in addition to the Jews', that it becomes impossible to deal with. But like any pilgrim, people who come to Auschwitz-Birkenau want to experience the "real" thing – they may not get the slice of enlightenment they hoped for, but they do at least accomplish the seeing they set out for. What is hardest to swallow about IDEA's proposal is the knowledge that someone who has already seen this has decided that no one else should, or at least until the logs rot to nothing and the site's memorialization is passed onto future societies. Whatever the opinion on the aforementioned selfie, doesn't this infringe on future generation's rights to visiting Birkenau? What right do we, in our present history, have to intervene?

16 Comments

"We might as well memorialize the night sky."

I like the quote above.

The one thing I think about, when it comes to the Holocaust is this idea that survivors, and enablers, are dying and soon the possibility of any true reconciliation to happen is lost. Should the sins of the father[land], be passed on to their progeny? Is it possible for anyone to consider Germans, or Germany, without wrapping them in guilt, or are the Germans born today, tomorrow, forever caught by circumstances not of their doing?

When I left Vienna I had a few Schellings left, enough to buy some skate board degenerate and myself an old Mcquick burger (French McDonalds knock off) on back grill. I had food poisoning when I visited Auschwitz. I threw up before the room filled with glasses and thereafter maintained a quezziness until I puked my guts out at where they baked humans.....

^Quick is actually Belgian.

I don't think it's even appropriate to consider reconciliation as a purpose. Those who suffered will never be made whole; those who perpetrated cruelty should never be absolved of guilt. It trivializes things to suggest any post-fact intervention could change that.

At the same time, wrongdoing really is only a condition borne by those present for the situation. There is no reasonable purpose in expecting guilt from the descendants of the guilty - and the much larger group who are associated only by language and geography. The only purpose of the memorials should be to remind the public the extent to which cruelty exists within all people - and maybe to warn us how easy it is to let it happen. Such a memorial can only exhort us to resist.

It seems profoundly distasteful to imagine hiring a crew to rebuild the camps, of paying people to spend time from their lives maintaining a terrible place which should never have been allowed to exist. Upkeep is a form of reverence for a place, a celebration of the culture which established a building. No such thing is appropriate here.

There is no magic in the buildings. Nothing to be learned or studied or worshiped. Let them decay naturally - keep the space forever empty, as haunted land. The site itself is the memorial. Any useful or didactic information is conveyed by the history and documentation of the terror.

mid, did you even read the piece? are you familiar with truth and reconciliation commissions in south Africa?

i'm not suggesting that Jews and former Nazis get together and sing kumbaya. I am suggesting, as my allusion to the bible notes; the children of those that stood by and watched this happen, shouldn't be held to atone for their parents, grandparents sins.

Beta, how does a memorial have anything to do with "wrapping [German youth] in guilt"?

An Auschwitz memorial serves as a reminder that horrific carnage can occur in ostensibly advanced societies (think of the art, architecture, and ideas that emerged out of Weimar Germany, which preceded the Holocaust). Auschwitz (which is located in what is now POLAND) serves as a cautionary reminder to the world, not just Germany.

I'm not really following the design proposal, to be quite honest.

Is that a serious question?

I think on a very basic level, memorials can perpetuate hostility towards peoples not involved, look at ANY controversy surrounding the memorial for 9/11 and the location of an Islamic cultural center. Did those people, who had an Islamic Cultural center located near the site, prior to the re-design, deserve that kind of hate? I think there's a tendency to hang an albatross around the necks of those that had nothing to do with the Holocaust, and going to these sites, I do wonder; how do people move on, reconcile their pasts, and to unburden those that are burdened. Auschwitz, yes, is in Poland, but we all lay the blame at the feet of Germany. As for cautionary tale, well, Serbs and Croats, and many in the Sub-Continent can't wait to hear how that tale finishes.

It is a serious question, indeed. :)

I don't think that the analogy you're drawing about the 9/11 memorial and a Muslim cultural center is fair (comparing Islamophobia in the US to global recognition of the Holocaust is another can of worms that I don't have the energy to open this Thursday morning).

Non-German nationals (Poles, Hungarians, the Vichy French, Lithuanians-- the list goes on) had a hand in the genocide, and, as I mentioned before, the site serves as a reminder to humanity and not just Germans.

Your argument basically boils down to: "contemporary Germans shouldn't feel bad about what happened in the past," so we should just erase any and all testaments to them. Please tell me how awareness of the Holocaust through memorials has harmed Germans in any way.

And, to your last point-- it's precisely because the Bosnian genocide occurred that the Auschwitz memorial, and memorials like it, serve a purpose.

No, that's not my argument. I'm not advocating the erasure of these sites, what I am stating is I believe the there exists a stigma, that many bear - and despite your citing of European actors contributing to the Holocaust, you neglect to point out America certainly didn't enter the war to save Jews, and in fact there was rampant Anti-Semitism in America that likely prevented us from engaging sooner - in Germany, today, so much so, that we now see an re-escalating nationalist tendency in Europe. So, is it the premise that it remains unresolved, undiscussed, unforgiven, or what? Or, would you rather have it like what currently exists in America, where no one, but the Native peoples talk about genocide, and the rest of America get defensive about NFL football team names?

I think my analogy is correct. Many in America want to label Muslims as terrorists, many people look at Germans and see Nazis. I remember living in Germany as a kid, 30 years removed from the end of the war, and I felt it every time I played with kids in the hood, saw german military, visited former german bases, towns, villages...

What are you proposing re: Auschwitz, then?

I like this work, I like what they are proposing. I think it's appropriate. I also think that revisiting the site as stated here: "Over time, the logs would be allowed to decay, prompting another reconsideration of the site." is very important. I also think that not forgetting, does not inherently mean, not forgiving. Perhaps, as people, we can also reconsider the total human cost, the shame...

I think on a very basic level, memorials can perpetuate hostility towards peoples not involved, look at ANY controversy surrounding the memorial for 9/11 and the location of an Islamic cultural center. Did those people, who had an Islamic Cultural center located near the site, prior to the re-design, deserve that kind of hate?

no, but I'm not following your logic...how does a memorial perpetuate hostility? The way a memorial memorializes an event "can perpetuate hostility" but the "memorial" as a typology is innocent until proven guilty. The Vietnam memorial does the opposite of what you accuse. It marks the war as a scar which implies a past misfortune rather than an ongoing conflict. The 9-11 memorial seems appropriate imo. Its very site specific and does not in anyway point to outside places and peoples but instead simply marks a tragic event and creates place around the memory/ruins of that sad event.

Beta - I don't disagree with your last post. Indeed, I think that there has been a great deal of forgiveness, it Israeli-German relations are any metric. Of course, the issue is more complicated than that and implicates some collective psyche, but just saying...

Sure, you go on and believe that. In fact, you miss my point altogether, and readily court selective amnesia. The 9/11 memorial plans to show a film that interfaith leaders object to;

"An interfaith advisory group of clergy members in New York is raising concerns over a documentary that will be shown at the National September 11 Memorial Museum when it opens next month, arguing the film is offensive to Muslims.

The film, "The Rise of Al Qaeda" refers to the 9/11 terrorists as Islamists and uses the term jihad, which has panel members worried the film will leave museum visitors with a prejudiced view of Islam, The New York Times reported.

"The screening of this film in its present state would greatly offend our local Muslim believers as well as any foreign Muslim visitor to the museum," Sheik Mostafa Elazabawy, the imam of Masjid Manhattan and member of the interfaith group, wrote in a letter to the museum's director."

Another point, the siting of a new Islamic center, near the site, was vehemently objected to. Also, I dare say, that a memorial commemorating dead Vietnamese by American soldiers brings up a lot of complex emotions. Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, etc...I am saying, complex events, over time, do not create simple emotional responses.

I am saying, complex events, over time, do not create simple emotional responses.

they don't. That I agree with. No one builds memorials to the victims of bubonic plague...too long ago to care about...we memorialize recent events....the memorials of today become the historic sites of tomorrow. We don't weep at revolutionary war memorials...I think 80 years is the cut off point for caring about people. If you were tragically killed greater than 80 years ago then we just don't care...I think the equation is something like (time past x distance = degree of not giving a shit)

I thought that Zaha was doing the bubonic memorial...

Beta - I got emotional and responded before I read the whole proposal - my mistake.

My stance is that it's a gross trivialization of what happened to propose any sort of ceremonial installation at this site. It's a misappropriation of art to do anything that attempts in any way to mitigate the disaster or pretend to create closure. Ideally the sites would be left as open sores on the Earth, reminding everyone of the depravity humanity is capable of. I despise the idea that someone would be thinking of ways to make something "beautiful" here which could later be listed on a CV or portfolio for professional recognition.

I also totally disagree with the idea that reconciliation should be a purpose here. Reconciliation isn't a moral act - it's a process of compromise done as needed to allow future peace. It's also a political act more than a memorial process.

In a situation where most of the victims don't survive, no real reconciliation is possible. After this few Jews or other victims remained in Germany. And by thoroughly eliminating the German populations which formerly inhabited East Prussia (eg the Russian exclave formerly known as Koenigsburg) and many mixed-ethnicity areas of Poland the Soviets obviated any need for reconciliation. There was no more mixing of those associated with victims and those associated with perpetrators.

In general I don't see a lot of hostility towards modern Germany nor individual Germans; I think most reasonable people accept that they have no control over what their predecessors committed. And it seems generally the case that modern Germany recognizes the terror committed, and continues to fight the cultures of nationalism, militarism and Nazi ideology which let it happen. It probably helped things move forward that East and West Germany were utterly divided for a generation, and any perception of continuity with the fascist state was extinguished.

I do agree that a memorial can perpetuate hatred - sometimes that's the purpose. See the Japanese War Memorial as an example how that can work. But again that isn't what I see happening in the Holocaust sites.

The 9/11 memorial is a much different situation in so many ways. I could say a lot on that, but not here not now.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.