Keller Easterling is an internationally-recognized architect and theorist working on issues of urbanism, architecture, and organization in relation to the phenomena commonly defined as globalization. Her latest book, Subtraction, is published by Sternberg Press. Easterling is a Professor of Architecture at Yale University.

Mitch McEwen: Should we jump into the Subtraction?

Keller Easterling: Sure. I confess, I don’t have any prepared answers

MM: Should we start with Detroit? Detroit, just in terms of how it operates, in the book?

KE: The rust-belt cities, shrinking cities have been shrinking for as much time as they have been growing. These are fascinating to the Subtraction project because the failure is so spectacular that something almost magical happens, where all of the kind of trafficked mortgage products stop being trafficked mortgage products and turn back into heavy landscapes and houses again. Things back in a gravitational field, things made of material, things that have taxes due, mold in the pool, you know. They go back to being kind of obdurate objects. And that is fascinating because it kind of prompts a parallel market. It means that one has to deal with the market of spatial variables. One has to trade in spatial variables, not only financial variables. Because the financial variables have failed.

I was talking to somebody in New Orleans last week because I was trying to write something about subtraction and the ocean. Both in Detroit and in New Orleans, they are kind of getting together as sisters with the same problem. What they’re saying is supposedly bad is: “The financials don’t work.” But I’m wondering if that’s not such a bad thing. A kind of spatial hedge against financial disaster might be productive.

MM: That’s one of the things that’s really fascinating to me about the way that you’re working with economy - that something like a spatial hedge, the possibility of that emerges.

In your work, you open up this idea of hacking or working in the failures. I’ve been interested in risk in these situations. Because in financial derivatives, as you just brought up, we’re used to thinking of hedging of risk in financial systems and markets as something that’s going to be related to reward. High risk, high return. When risks are related to financial instruments, it’s acceptable that there will be a reward there. But if there’s a [spatial or physical] risk - a moldy sink, or risk of a boarded up house, or risk of the 9th ward being flooded, somehow the calculation of risk becomes one of people being blamed for putting themselves in that situation. It becomes this argument that: you never should have been in this house with that sub-prime mortgage, you never should have been in the 9th ward when it’s close to the water.

Related to that -- with Detroit as a kind of backdrop-- what you produce with this notion of a subtraction economy seems so incredibly productive and imaginative. Could you talk about how you have been bringing economics into this world of architecture?

KE: Well, I’m trying to do it more now that this book is out. I’ve been trying to engage proper economists in talking about this. So far, unsuccessfully.

Because I’m an architect, it’s super important to make the distinction between this idea of subtraction and the architects’ cliched love of the tabula rasa. Subtraction is broader. That’s a completely different kind of urge, and a few people who’ve read this book have still got the sense that that’s what I was saying.

MM: Even though you’ve got this whole chapter, that whole chapter on tabula rasa.

KE: I know. It’s still just so ingrained in culture to think that if you’re subtracting something, it’s for its replacement by a better thing. Or something like that. But what I’m trying to think about are interdependencies-- financial, economic, spatial instruments, that set up an interdependency between properties and things in a city.

I keep coming back to this example of Savannah, Georgia. In that arrangement, you could not have a certain amount of public space without a certain amount of private space, without an allotment, of a certain amount of agricultural space beyond. The linkage between properties is the thing that interests me. So that one is not making just subtractions as wiping away, but you’re making interdependent subtraction and additions, or other kind of interdependent relationships that potentially stabilize spaces and finances.

It’s not as if I know what those things are. I’m suggesting what might be just a habit of mind: between interplay, between parts. It seems to me that we have a fair amount of difficult bureaucratic technical instruments that are part of just getting a mortgage, that are part of the way that banks and insurance companies game that transaction. So, I don’t see any harm in adding some more layers, even some layers of interdependency or cooperation between properties that maybe even strips away some of the crazy bureaucratic stuff like points, and may simplify some kinds of property transactions and property life cycles in a city.

MM: The points that you’re talking about-- is that tax abatement, or LEED...?

KE: Oh no, no. I’m just talking about the financial industry’s games that they play. If you get a mortgage, you get points.

ME: Oh, credit scores…[Note: the “points” Easterling referred to may be interest rate percentage points on debt.]

KE: There’s tons of things like that, that are layered onto the transaction of buying a property or getting rid of a property. Another thing that’s so great about the crisis-- I talk about this a lot in the Subtraction book-- is the emergence of land banks.

MM: Yes, you do talk about that. Yea, in Detroit, yea.

KE: The book talks about land banks as something that wipes all that away. It just becomes a piece of land again. The thing that’s being stored is land. The land banks aren’t necessarily doing this, but I think they could become the place where people discover what those interdependencies between properties are. Now it’s already kind of informally happening, where a land bank is a place where all kind of agencies in a city need land for different things. There are already these little funny cooperations between functions in a city that need land and land banks. I think there could be all kinds of relationships like that. We might have land banks without a financial crisis. That’s two things that, for instance. New Orleans and Detroit share: this emergence of new middle institutions.

MM: It’s funny I only became aware of that in Detroit recently. And then just this week, one of my neighbors of the house in Detroit took a photo that the land bank had posted, that I had 3 days to contact them, that they were seizing the property.

KE: Really?

MM: Yea, and it’s kind of fascinating because it’s very hard to trace the authorities at work. I had mail coming from the Wayne County tax office the treasurer, that I had to respond to in person, about 2013 taxes. That’s another whole issue-- that I can never find out out the taxes [due] until it’s almost too late, you know. The information flow is such that I don’t find out what’s owed until they are about to take something away. But then the Land Bank, when I finally got them on the phone -- after being suspicious that they might be a hoax or something-- when I finally got them on the phone, they said that they are separate from the County Treasury office. They are part of the City. And that whether I paid the back taxes or not, they would still be able to take the property. So, an attorney’s going to call me. The house keeps being this honey trap. Whatever is being engaged at the moment, I engage it.

KE: How are you affording to hold onto this thing?

MM: Well, it really doesn’t cost that much. It cost $1,100 to buy, and I had a fellowship. That was my stipend for a month. And then it was about $2,500 in back taxes, which my artist friends put forward. So they are co-owners now. It’s sort of becoming an artist residency, the design that I’m working on. What I’m trying to do is just record and document as much as possible what happens.

KE: So, the land bank- how did you prevent them from seizing the property?

MM: Well, I haven’t yet. That’s the thing. There’s a stipulation on the foreclosure auction, which I participated in, which basically says that if I didn’t get the property up to code within 6 months to a year, the auction could be reversed.

KE: Oh, you have to get it up to code. Oh.

MM: At that point I’d rather just demo it.

KE: Yea. In the Subtraction book, there’s a really great image from Dan Hoffman.

MM: Do you have that here in the book?

KE: Yea it’s in there, it’s 9119 St Cerle.

MM: I was so glad about this reference.

KE: He did this super cool thing where he took [a house] apart. He did it as a tear-down. So, he took it apart and then sorted all the pieces. So there were these barrels of very carefully stacked pieces of lathe and stuff like that. It was exactly like a tear-down performance. It was 1984 or something like that. That could be something you could do: you just inventory the parts. Because it’s expensive to get it demoed, right? It’s probably going to cost you another ten thousand, X thousand dollars.

MM: Yea, it costs the city ten thousand. There are a couple organizations in Detroit that do what they call ‘people powered’ demos, where there’s literally no power tools. I might do something like that. It’s funny because I tried to do something like that with the yard. I had more piles of wood than I could get taken away at any one time.

KE: Are there agencies that organize people or industries to act as an employment agency or something to get people together for these demos?

MM: Totally. Yea, I think I would work with an organization like the Blight Busters and do a set of drawings that’s like a very careful demo set. Because they have the labor and they’re used to working a certain way.

Your book is super helpful, as this amazing collection of all these different tactics.

One thing I wanted to get back to: When you were talking about interplay and how it relates to economics, I wonder-- because you are talking about opportunities within this field of subtractions and these failures-- How are these opportunities distinct from the sort of Richard Florida “Creative Class” modes of interplay in the city? i.e. Not something like the usual “artists make a place cool” patterns of gentrification?

KE: Well, I guess I’m thinking that these are things that are not one-off actions, but entrepreneurial efforts that then become institutionalized, that then influences government, but not the other way around. Not starting as policy, because that’s impossible.

For instance, I’m just trying to write something about this coast situation and the retreat of the coastline. There are plenty of NGOs like ISO who rank and certify things. They’re just self-appointed, private NGOs who provide stamps of approval and ratings and ranking and things like that. It’s strange to me that architects and landscape architects and regional environmentalists and so on are not part of an agency or NGO that rates properties in some way.

There’s a kind of entrepreneurial effort that might be one of those things that gives value to properties. Right now you think of a property as one that might have a mineral rating. It might have a wind rating. It also has a risk rating, usually to do with insurance, if you’re near the water or something like that. Might there be another kind of rating that has to do with the experience and expertise we have about an interplay between properties that would even facilitate swapping from high ground to low ground or densifying in a place like Detroit? The challenge would be to try to have some kind of indicators that were associated with the property that lead banking and insurance, rather than the other way around. To have a rating of property for all kinds of factors that have to do with urbanism-- not just flooding or blight-- might have a beneficial effect on insurance.

MM: I hear what you’re saying partially in response to the question about gentrification. In your work, you use language that we’re so used to hearing in relationship to financial instruments and these other things that we think of as being part of a developed civilized society, and then when we hear them in regards to space and architecture, the terms sound so foreign. And we realize that architecture is still stuck in the 1300s or something. Architecture really occupies a different realm in terms of the complexity, not of form, but of these kind of aspects, right?

In a way, it seems that part of what we’re used to in terms of looking at urbanism in relationship to demographic shifts -- one of the reasons why artists and gays [like me] and people who are lead gentrifiers can have so much agency-- is that we are the people doing those ratings, instead of architects, right? It’s like the gay people are the ones out in the city trying to figure out what space is doing what in relation to different zoning parameters. For instance, in the Meatpacking District, how these spaces can be re-appropriated and made into nightclubs or something like that. Or the artists are doing that.

So, in a way it’s because these instruments don’t exist transparently that we rely upon these very vague demographic trends to even understand what might be possible in the sort of transformations of cities. If architects did participate in that, we might be able to share agency in these types of interplays, the same way that we’re able to share beauty and form with society.

So that makes me want to talk about drawing. What would be the methods of drawing of subtraction?

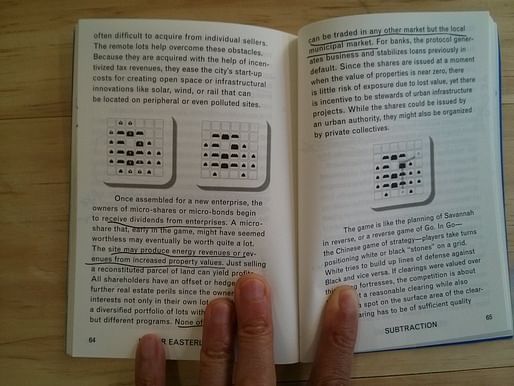

KE: Well, I tried to make it graphic in that little game, that reverse game of Go. I really did mean for it to be like Go. That’s really a kind of a calculus, I think. You’re really always thinking about something as a function of something else. You could probably do a game theory matrix of it, where you figure out in any one situation what the best response is. And the thing that you’re valuing is clearing and then being around the clearing, but not killing the clearing. It’s a tricky kind of game. You have to anticipate multiply players.

It becomes graphic and something familiar to planners and architects if you think of it almost like Bryant Park, where they figured out: here’s an open space and the perimeter-- the surface area of it-- yields this much more in rent. Or, the Highline, which also does the same thing. It actually has the same amount of acreage as Bryant Park, but a lot more surface area. So, it generates all this potential rent along its edge. At the same time, if everyone built tall buildings right around it, they would kill the clearing. They would make a tunnel out of the clearing.

It’s like a tricky game that’s told in spatial variables, and it’s graphic. It’s got to be graphic. You can’t ignore the volumetrics of it, which is important, it seems to me. I like those kind of games, and urban design in which space is leading the financials, and not the other way around. It’s not just abstract financials, which can be something threaded through a Swiss bank account anywhere in the world, and no one really knows what it is. It’s a physical volumetric thing that is influencing financials, and it makes our intelligence lead it.

So, that’s where I think it’s graphic.

MM: The way that you were just talking about the spatial variables leading the financials, it sounds like a very clear explanation of how you end up working on oil, also. There’s the notion of this subtraction as an active operation that renders durable these buildings that were once commodities. And then you have this commodity [oil] that is so pervasive in abstract economies. They almost seem like opposites, like other ends of the process that you’re tracing. In the Subtraction book this comes up a little bit as far as South America, right? It comes up in terms of the exchanges that are set up in South America that you research.

KE: Yea. There’s another example not unlike the land banks, where there’s some kind of intermediate institution there. I visited a part of the Amazon called Socia Bosque, which compensated farmers for not farming. Obviously, the questions are how to harness the ongoing values of that not-farming. Now we have a carbon market, but that’s incredibly technical and quite difficult for farmers to work on. I keep again wanting to put forward some simpler spatial variables that can become part of global governance, where the spatial variables can help to solve some intractable problems that aren’t being solved by the technical markets-- either financial or carbon markets in that part of the world.

There’s that example that you know about that doesn’t exist anymore, the Yasuni protocol. They were basically selling certificates that just had to do with the land-- the beauty of the land, the biodiversity of the land, the indigenous cultures. It was basically the ratings and scientists who said: this is the most bio-diverse place on earth. So Carrea said, ‘OK we won’t drill the 20% of this country’s oil that sits underneath it, if you give us money.’ So they were, in a way, taking that value and making into something. And I just want to find more and more examples like that. Where there’s stuff we know is valuable, but we have no way of valuing it within the kind of halfwit financial and economic systems that we have-- systems that only do certain kinds of things, that only drill down and gain tiny little meaningless things. Whereas, we have all these huge, heavy durable meaningful things that we’re not able to value.

MM: You mentioned earlier that you were reaching out to economists, to try to involve, as you said, ‘real economists’ in this. You’re already kind of becoming an economist it seems, in addition to being an architect.

KE: I’m not. But, you know what’s so amazing is how economists and people who are some of the real innovators in the world just have no respect for what it is we do.

MM: Right.

KE: One super interesting guy named Gus Frangos, who’s head of the land bank in Cleveland, the Cuyahoga Land Bank, has done some of the most innovative land bank stuff in the country. He had the brilliant idea of going to the city and saying, ‘Please, give us the amount that you get in for delinquent taxes. Give us that money as the budget for our land bank.’ And it ends up being $7.5 million. Nothing compared to what is owed on delinquent taxes, but the idea is that they would be making money for the delinquent tax agency in the city and getting money to properly fund this land bank. So, it’s just this genius move. And it’s that kind of thing I’m super fascinated with. But, when I talked with him, and I explained why an architect might be interested in this, they think you're interested in-- I don’t know-- putting shutters on the houses or something like that. Something like that came up. ‘You wanted to color it, paint it, put shutters on it,’ or something like that. It still always starts with financials. It still always leads with financials.

In the the class on entrepreneurialism that I teach, which has some students from Yale’s business school (SoM) and the Law school, we talk about trying to lead with spatial variables. But when a powerpoint comes on and there’s a McKinsey report or something, all the management students and law school students say, ‘Ah, finally something I can use.’ They’re totally honest, there’s nothing wrong with what they’re saying. They’re right. The variables of competence and variables for making anything are not spatial. We really missed the boat in having any kind of authority. I mean, not that it can’t happen, but we don’t have it yet.

MM: I wonder if I could relate this back to the question about drawing and methods of drawing. You responded to that with a game, which to my ears sounds like programming, right? It sounds like drawing through setting up sequences and recursive operations, drawing with the tools of programming. I wonder if-- in relationship to things like economic theory, which you’re already delving into-- is there something about the capacity of projection to develop authority? Because, when you think about the type of drawings that you’re talking about as programming, then drawing and projecting become a sort of continuous act, right?

It seems like there’s an authority that economics has in being able to chart and be mathematical. It’s a kind of authority that is recognized as a type of intelligence. But, also, there’s an authority about being able to forecast, that’s maybe even distinct from the sheer intelligence of it. I wonder-- is there a way that we can participate in that, as architects, as spatial people?

KE: Yea, absolutely. Absolutely. There are people who’ve been really good at that from the tradition of the RPA and the tradition of-- well now it’s confusing-- the RPAA, who’ve tried to constantly visualize the spatial consequences of economic growth and other factors. Lots of people are trying to visualize that. Then there are people, like the New Urbanists, who make compelling images that have influence. Absolutely.

The house has been an economic indicator, at least since 1934, and before that, too. The house as an economic indicator is something that’s fascinating to so many people. Even this new book by Piketty looks at this- at the numbers of the house and its sales as an economic indicator. Nobel Prize winners are looking at the house as an economic indicator. The financial crisis also brought that forward in the news. Also, the data crunchers in the New York Times were doing all those kinds of visualizations.

But there’s more to do still for the urbanist. Much more to do.

Posts are sporadic. Topics span architecture, urban design, planning, and tangents from these. I sometimes include excerpts of academic articles.

4 Comments

Damn good blog post Mitch! Just ordered a copy of the book, same publisher of my recent Douglas Coupland purchase (Shopping In Jail)....and Savannah, GA :)

Below is a quote of something I just read, but had to put it down. Hegel and Marx related texts need more attention than a commute can deliver, but relevant to this post, from "Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defense" by G.A. Cohen:

"Space deserves membership in the set of productive forces. Ownership of space certainly confers a position in the economic structure. Even when a piece of space is contentless, its control may generate economic power, because it can be filled with something productive, or because it may need to be traversed by producers. He who owns a hole, even exclusive of its material envelope, is a man to reckon with if you must reach the far side of the hole, and cannot feasibly tunnel beneath it, fly above it, or make your way around it.

Thus on our account of the economic structure, space looks like being a productive force. But is it used in production? And does it develop in productivity over time, as productive forces are supposed to?" p.51

_______________________

Not sure how much this could help better understand economists, as it's a personal story, but one of my younger brothers is an Economist in D.C. He and I converge at Philosophy and Mathematics.

The feeling I get is an Economist spends a very long time looking at data, then looking at meta data, then relations of meta data and data, then begins to formulate (makes formulas of the relations of data sets), then they go from bottom of the pile to the top and back down again until a very 'attractive' formula develops that can guide politicians in decision making . An 'attractive' formula worthy of a Noble prize or something.

My brother is on the accumulating and publishing end of the data (Census Bureau). We both are skeptical of the big names in our respective professions. As I understood him - my brother is quite amused and skeptical on how the big names take the data he has published and proceed to make their 'attractive' formulas that appear to summarize the past well, seem to be gauging the future presently fairly well - a short time period - but just long enough for a government agency somewhere in the world to take the 'attractive' formula and make it policy. As he suggests, I put that data together, it's edited to some degree.

With that said, I think I mentioned wanting to work with economists on stuff and he said to some effect - you architects (me) take data, make crazy concepts, shuffle everything around and come up with barely plausible yet creative ideas, etc...I more or less responded - SO? Isn't that how innovation and research happens? He recommend I should find an overly ambitious Economists who wants their name in the headlines. They would be interested and finding the 'attractive' math formula to make my constant new-fangled ideas appear worthy of policy making.

Again - great post, enjoyed it!

Design Ninja, Thanks so much for your long comment. I'm always glad when folks appreciate Keller - she is really amazing.

As far as economists, I would say there are many ilk of economists that we research-oriented architects might collaborate with. Behavioral economists come to mind. There is a great book out of MIT/ Harvard called Poor Economics, which would overlap well with a lot of local activist design methods. Also, as far as theorists, Gabriel Tarde is really great. Bruno Latour wrote an introduction for his book, through Tarde was basically a contemporary of Marx. But he modeled economic production on publishing instead of corn, so it lends itself well to globalization.

Thanks for your comment.

Thank you for a blog with Content and the reading list - looking forward to future posts.

"(Social) space is a (social) product. This proposition might appear to border

on the tautologous, and hence on the obvious. There is good reason,

however, to examine it carefully, to consider its implications and

consequences before accepting it. Many people will find it hard to endorse

the notion that space has taken on, within the present mode of production,

within society as it actually is, a sort of reality of its own, a reality clearly

distinct from, yet much like, those assumed in the same global process by

commodities, money and capital. Many people, finding this claim

paradoxical, will want proof. The more so in view of the further claim that

the space thus produced also serves as a tool of thought and of action; that in

addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and

hence of domination, of power; yet that, as such, it escapes in part from

those who would make use of it. The social and political (state) forces which

engendered this space now seek, but fail, to master it completely; the very

agency that has forced spatial reality towards a sort of uncontrollable

autonomy now strives to run it into the ground, then shackle and enslave it."

Lefebvre, Production of Space

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.