Mahalia C. Gayle is from Seattle, WA. She completed her undergraduate studies at Princeton University and her graduate work at Harvard University, both in Romance Languages and Literatures with a specialization in French. She has taught at Harvard University, Boston University, Emmanuel College and Princeton University.

Mitch McEwen: Your new book project is concerned with politeness and its relationship to aristocracy or republican identity. As I mentioned, this may be a pertinent lens for architecture, as well.

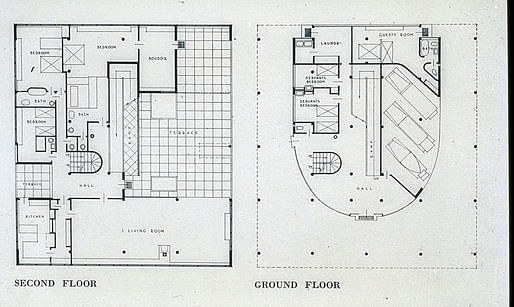

Mahalia Gayle: Politeness regulates proximity to the powerful body or proximity between bodies of unequal power. I thought you might mention segregation or service entrances in this connection, as they are one way in which politeness can be expressed in architecture, but I will try to answer as best I can…

[Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye, ground flr and second flr plans, servants quarters on ground flr with garage and laundry]

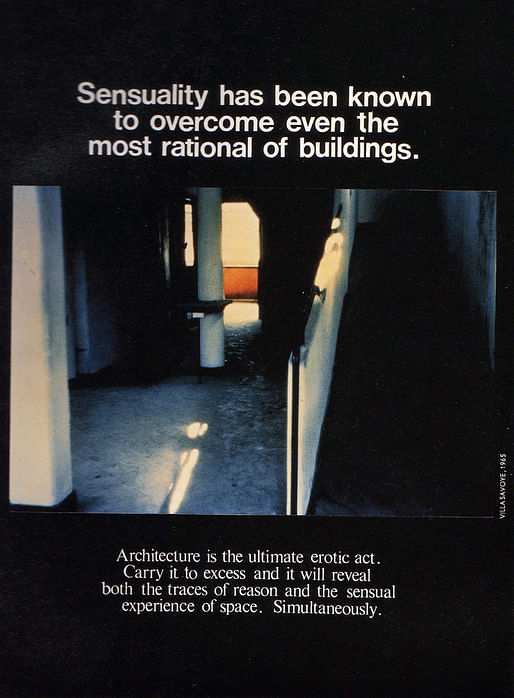

MM: Let's talk about your work on Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Architecture continues to struggle with its relation to fascism. There is a certain rejection of monumentality that happened in avant garde circles in the 1960s and 1970s that relates to this. Super Studio in Florence or Bernard Tschumi in NYC were key examples of this critique of monumentality. As far as the history of Fascism in built architecture, Albert Speer remains a complicated figure.

[Bernard Tschumi's Advertisements for Architecture, 1976-1977]

[Bernard Tschumi's Advertisements for Architecture, 1976-1977]

I am very interested in your analysis of Drieu for this reason. You write: "Drieu’s fascination with style and hatred of the democratic elite of money and university diplomas lead him to imagine a fascist elite which, through biological racism imitates the cultural racism of aristocrats."

Can you talk more about how politeness plays into this imagination of a fascist elite?

MG: Yes. My work explores themes specific to France, though there are connections to fascism in other countries because some French fascists were also internationalists. When I say “republican”, I am contrasting it with “monarchic” and “aristocratic”.

Drieu la Rochelle hates democracy because it is not organic as the traditional elite claimed to be; they were the natural leaders of France, they owned the land, they were France. He liked the fact that they were haughty and that their status was a gift of high birth. He also dislikes democracy for aesthetic reasons. He can accept admiring a well-dressed, well-spoken, good-looking or distinguished, suave, lofty French gentleman with an evocative history of chivalrous military heroism... He doesn’t want to be equal to average people, but to extraordinary, stylish people. The sartorial distinction of the nobles made other people look unfashionable, if not shabby. The linguistic distinction and conversational style of the noble make other men sound dull. When, in his writings, he criticizes some men of his acquaintance, it’s because they have bad style. They cannot live up to the stylishness of the traditional elite which is on its way to being replaced by businessmen who have no romantic history, no ideal higher than making money.

MM: Also very pertinent for architecture is your distinction between style and sexiness. You write of "The rise of the importance of sexiness..." Say more about the distinction between style and sexiness. Where do we track it in literature? How do social mores and the performance of the polite transform from style to sexiness? Can one paradigm subsume the other - i.e. is sexiness just one mode of style?

MG: It seems to me that with style, more than with sexiness, there is more mystery, mastery and… distance, more space for negotiation with physical realities. In France there is a move from a society in which, the exemplary, elite person takes up a lot of “space” and commands deference because of their power to a situation in which individual bodies become powerful because of how they look. In literature, you can see the change by the way that people are described in different eras, by the aspects emphasized by the describer.

To me, style is less obscene, less aggressive than sexiness, it is more discreet. Style may be more alluring, beguiling while sexiness might be more overt. Being a good conversationalist or being well dressed is not the same as looking great while undressed, although the two can be related. What is conversation? Why do we like certain people more than others?

Having good taste is an expression of the personality, whereas being naked or being dressed in clothes that evoke nudity focuses on the dominance a person can have because of the gifts that youth (or athleticism) gives. You can be stylish despite ageing, for example. Style is more witty, more human/voluntary than sexiness, which is more animal and more fleeting... If we take up architectural terms, sexiness might be a building with all the ornamentation on the outside.

MM: We have been talking about social class and style. Coming back to politeness, is there no performatively democratic role for politeness? Does politeness only operate stylistically and, in this sense, remain specifically aristocratic?

MG: I am glad you asked. Because politeness is related to influence, feelings and preferences there is a way in which it is highly political and related to radically inegalitarian worldviews and passions. People don’t automatically change the way they actually act just because all men have been declared equal. This explains my interest in people who reject egalitarianism outright: aristocrats, fascists, and segregationists. However, inequality does not have to be vertical, it can be horizontal. In a sense, the democratic ethos aims to replace a hierarchical estimation of people with something more horizontal. As 20th century horrors have made clear, such a replacement can be hotly contested. If there is a real acceptance of the fact that people are different—and this is a big “if”-- there is definitely a democratic role for politeness.

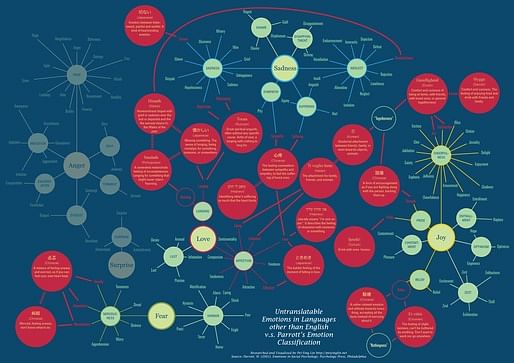

[Untranslatable Words in Languages other than English, v.s. Parrott's Classification by Pei-Ying Lin]

[Untranslatable Words in Languages other than English, v.s. Parrott's Classification by Pei-Ying Lin]

One description of politeness characterizes it as the performed love of equality in the absence of equality. It is a creative act in the face of ever-changing social realities, and we need such creativity today. In terms of style and self-fashioning, politeness is democratic because, though not everyone will fashion themselves in the same way, each person is free to perform a work on the self.

[All images selected by Another Architecture blog]

Posts are sporadic. Topics span architecture, urban design, planning, and tangents from these. I sometimes include excerpts of academic articles.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.