NO ONE CARES ABOUT AMERICA’S STUPID ARCHITECTURE PROBLEMS

The United States is accustomed to being the center of global networks in pretty much any field: film, finance, the art-world, pop music, development economics, tech start-ups, military strategy, and much more. Architecture, though, is an exception. Let’s face it: in terms of USA’s global significance, contemporary architecture is the creative equivalent of soccer. Europe and South America dominate the scene, with the US trying to hold on to some relevance on the world-stage. (Perhaps if architecture were divided by gender the US women’s architecture team would also be world champions – but that’s another discussion.)

Team USA graphic by author. Taking the global-practice-as-soccer analogy a step too far….

Beyond any half-hearted nationalism, this semi-peripheral global status means that those of us theorizing and discussing contemporary architecture with the public in this country have a special responsibility. Because we are not the center of a global discourse, we need to be even more rigorous in our criticism. If, for example, our investigation of the local impact of an international exhibit-- or any project-- starts and ends with the citation of an anonymous website, we have, perhaps, not done our jobs. If we are really concerned with politics and controversy regarding projects sited in Detroit, there are real situations and struggles that deserve some national investigation in our architecture media. For example, the People’s Waterboard of Detroit or any of its 30-odd member groups might have comments regarding the relationship between corporate investment and resource access. Councilwoman Raquel Castañeda-López, the first Latina elected to the Detroit City Council, might have some critical insights about issues of gentrification and development. The Black Community Food Security Network, which has been around for decades, might be a great activist source to hear about land-use, property claims, and other local issues. This is not to mention the city’s planning director Maurice Cox, who might have something to share about planning issues in the city and how that relates to histories of injustice.

No one will seriously talk about this country’s stupid architecture problems if we don’t. No one else cares enough. So let’s do this. First, I’ll address the overall 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, the spirit of the thing, its terms, dispositions, themes and the feeling of it.

THIS VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE IS MOSTLY ABOUT POVERTY AND INGENUITY WITH SIMPLE MATERIALS. THESE ARE TWO DIFFERENT THINGS.

Walking into the Arsenale – one is struck immediately by the curatorial logic presented in the form of exhibition design. Aluminum studs hang from the ceiling, twisted from the act of removing them from the drywall they were mounted to previously. A wall of what appears to be tile or stone clads the interior and serves to mount text and video. Of course, on closer inspection it is not tile at all but drywall laid on its side, stacked. The taping edge has been removed. There’s a video showing as much somewhere on the wall, with Venice Architecture Biennale curator Alejandro Aravena doing this himself. More text explains that all the materials deployed were salvaged from the previous Venice Art Biennale’s demounting (a side-eye to the artworld, perhaps, for its excess compared to the more pressing politics of architecture). If the last art Biennale (curated by Okwui Enwezor) could be considered political in its content and diasporic geographies, this architecture Biennale wants to be political in its materiality and economy.

The Arsenale is full of projects with materialized sensibilities. Materials matter, and they are, for the most part, simple, monolithic, unprocessed -- “primitive” one could say if speaking in scare quotes. There are many design-build approaches. Reality is king here – generally an aching reality, a kind of sparse Brechtian sense of the real. It’s a reality of facts-on-the ground that continues the militarized sensibility implied in the title (“Reporting From the Front”). Militants! Life and death is at stake. Hence: burlap, bamboo, mud, brick...

Personally, I share Mimi’s Zeiger’s skepticism about the truthiness of the approach in the Arsenale. As she says, “Reporting from the Front's fixation on the authenticity of construction valorises the handmade without engaging with the real costs of labour at local and global scales.” The exhibit sometimes seems to conflate a concern for conditions of poverty with an admiration for simple material ingenuity.

Personally, I did not grow up but poor, but I grew up in a mixed income neighborhood of a city that was ravaged by the crack epidemic and ranked as the nation’s murder capital for much of my childhood and adolescence. My mother was an entrepreneur, and occasionally we had the electricity cut off, or the house listed as foreclosed, because one of mom’s legal clients owed her money or-- over-worked-- she had forgotten to pay the bill. When those things happened, we would inevitably eat the ice-cream in the freezer, laugh about it, and go on with our lives. No one I knew sat in the dark eating broccoli in such circumstances. All that is to say-- There is a dogmatic minimalism in Arevana’s approach that feels fundamentally aesthetic and not at all related to the issues of poverty. This may be why Zumthor and Norman Foster can fit into the Arsenale so easily. (More on Foster later...)

BeL architects and their giant model NeuBau. One of the few examples of mid-density or high-density projects exhibited in the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale.

Beyond militant aesthetics, themes of temporality abound in the Arsenale. Rahul Mehrotra’s research with Felipe Vera and José Mayoral especially stands out for its investigation of a city of 55 million inhabitants that forms on the Ganges River once every 12 years. Titled "Ephemeral Urbanism," this exhibit includes documentation of this Hindu settlement Kumbh Mela, which lasts for only 55 days along the merging of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers before disassembling without a trace. A plethora of research on this architect-less phenomenon is presented through drawings, maps, and videos mounted on bamboo scaffolding. In some ways, this temporary city may be the most exuberant and over-the-top project in the entire Biennale. The fact that it's already existing and coordinated without global specialists presents another reading of who gets to do the reporting in architecture.

Ephemeral Urbanism, installation of videos, maps, photos and drawings in the Arsenale (courtesy of Ephemeral Urbanism on facebook)

Eyal Weizman’s amazing work on Forensics moves in the other direction, recasting the disciplinary capacity of the architect as one who unpacks, analyzes and gives dimensions and narrative to contemporary realities. The globally-malleable skills of the architect here enable a sort of an archeology of the present. As elegant as the various material studies are throughout the Biennale, these forensic projects feel like the strongest argument for the political agency of the architect.

Perhaps the paradoxes of the Arsenale can best be summed up by Norman Foster’s contribution. A lovely geometrically-pure shell structure, the full-scale artifact is described as a drone-port for drones that-- wait for it-- deliver medical supplies. The organizational partner for this, beyond Foster’s Foundation, is an organization in Switzerland. No host organization in Rwanda is mentioned. Did anyone in Rwanda choose this project, or did this project choose Rwanda?

I must say, there is an oddly sincere colonialism at work in much of this Biennale. The Dutch pavilion, which dedicated their exhibit titled BLUE to the architecture of UN Peacekeeping missions, might be the most blatant case. That exhibit presents a quite literal take on Reporting From the Front as a both militaristic and architectural exercise. The architecture presented here is not at all about a forensic analysis of violence, but rather a humanitarian effort to leave a good building object behind for the parenthetically starving Africans. If you don’t believe me, their curatorial statement explains, “in this nomadic region of west africa, borders are fluid and shift with seasons; and there is a state of permanent crisis as a result of war, climate change, sickness and hunger.” (Perhaps the next study site will be in the UK?)

Hotel Azalai Salam in Bamako, Mali, courtesy of Google (not at all included in the Dutch exhibit on UN peacekeeping)

Hotel Azalai Salam in Bamako, Mali, courtesy of Google (not at all included in the Dutch exhibit on UN peacekeeping)

MOST NATIONAL PAVILIONS AVOIDED SHOWING ANYTHING LIKE NEW BUILDINGS

Many of the national pavilions present something like an open confessional space for architecture to talk about itself to its practitioners. This works exceptionally well in the award-winning Spanish pavilion, where even the exhibition design embraces open discussion by lifting up out of the way (Who cares about looking at the projects, anyway?). The secondary room (which got little attention in the media) frames a discussion of architecture’s big thinkers talking about Biennale-relevant issues, such as attempting to define Spanish architecture, the anachronism of nationalism as a framework for exhibits, and advice for young practitioners (e.g. Amale Andraos: be fearless and humble). The Spanish Pavilion serves as a coherent and thoughtful summary of much of the Biennale’s curatorial priorities: existing sites over new buildings; the residual effects of boom and bust economic cycles; the value of intervention and small scale works; the big thinkers of the discipline replacing big builders.

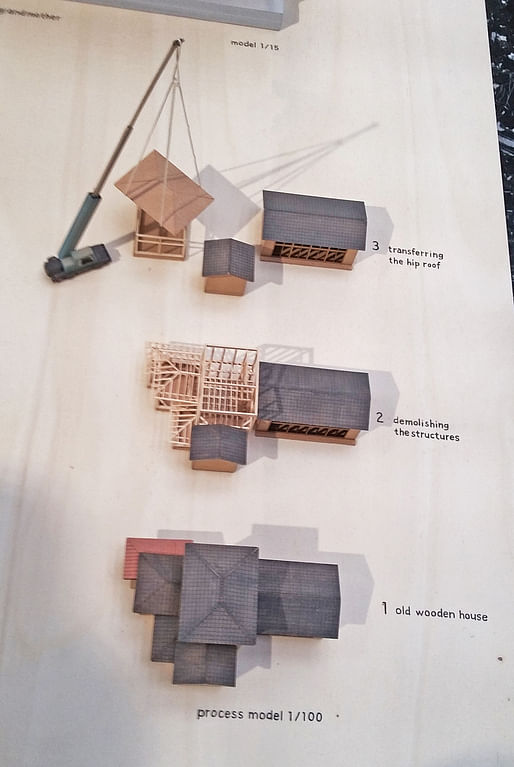

Model in Japanese pavilion – re-configuring existing 1 or 2-story buildings. This was a motif throughout the Biennale and especially rewarding in the Japanese pavilion.

Many pavilions-- such as Norway, Germany, Albania-- presented a spatial situation at the scale of the pavilion, as a means of framing a rigorous political economic and social analysis. Croatia, like Spain, highlighted projects working with existing buildings. But in Croatia's case the emphasis was not so much on conventional disciplinary ingenuity, but more an architecture without architects, drawing from existing realities without over-simplifying or closing off evolutionary potentials. In the curators' words the exhibit focuses on the transformation of "buildings that have lost their primary purpose, or were never even used as originally planned, into places of concentrated cultural production and social interactions." Objects and models present spaces taken over by community arts organizations. Musical instruments designed by the residents are included among the models, drawings, and photographs.

Croatian Pavilion The project titled We Need It – We Do It by the Croatian team of architects and cultural workers Dinko Peračić (also the exhibition's curator), Miranda Veljačić, Slaven Tolj and Emina Višnić.

THE US PAVILION STOOD APART FROM MOST OF THE PAVILIONS AND ARSENALE BECAUSE IT SHOWED BIG NEW BUILDINGS

The US Pavilion, in which I participated as a commissioned designer, put itself in the tenuous position of addressing civil society directly in its ambitions. The closing and standardization of format makes it clear: this would not be about architects addressing each other with new ideas about the figure of the architect (what could be new about a big model and drawings on the wall -- despite Gregg Lynn’s introduction of Hololens), but architects engaged with and presenting to a civil society. This is challenging in the US, since our dialogue about the built environment and landscape gets practiced primarily at a local level. NYC, LA, Portland, Chicago -- In these cities there are conversations about parks, waterfronts, combined sewer overflow, skylines. Where do we do that nationally, across cities and time zones? Arguably, only a small group of academics, a larger group of New Urbanist practitioners, and a handful of architecture critics at national newspapers engage in nationwide architectural dialogue. The US Pavilion stood out for taking the risky move of attempting to address a civil society, rather than craft a confessional space for architects to talk to each other.

Beyond this, the primary difference between the US Pavilion and the Arsenale was not so much materiality or formalism -- but density. If you have read the sparse US press on the Biennale you probably don’t believe this, so here are two examples of US Pavilion projects highlighting discarded or local materials. One project in the US Pavilion was proposed to be constructed entirely out of scrap materials (T+E+A+M); another is a Modernist social housing project that crafts a Meisian rigor out of local wood (Present Future).

Project by T+E+A+M, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Thom Moran; Ellie Abrons; Adam Fure; Meredith Miller) Courtesy The Architectural Imagination

Project by Present Future, Houston, Texas (Albert Pope; Jesús Vassallo) Courtesy The Architectural Imagination

The US Pavilion stands out awkwardly, but justifiably, in the Biennale for the urban density and scale of projects. For all the variety of materials, sites, and programs presented at the Arsenale and most national pavilions (w/ the exception of Korea), the vast majority of the work presented across the whole Biennale is 1, 2, or 3 stories. Much is at the scale of single family houses or interventions into existing buildings. A rare exception is the Korean Pavilion, which focused on Floor Area Ratio (FAR) as the theme of its investigation.

Korea: study of FAR, one of few exhibits other than US to show high density urban projects

US PAVILION IS ONE OF VERY FEW EXHIBITS IN THIS BIENNALE THAT ADDRESS URBAN DENSITY

As far as the role of density in speculative projects, I totally disagree with the (misinformed) cynicism of Architects' Newspaper, which cautions that the density of new construction explored in the US Pavilion for Detroit sites can only be achieved by large corporations. Three of the four project sites worked on for the Pavilion are publicly owned. Only the Packard Plant is a fully privately owned development site. The 3 other sites -- the Dequindre cut, Livernois garage in Mexicantown, and the Federal Post Office -- all feature a mix of publicly and privately owned open space and existing buildings. In order, these include: development parcels that straddle a major landscaped open space crafted from an industrial disused freight rail line; an old municipal garage and 10 acres of parking, and a federal post office with adjacent waterfront open space.

Perhaps the programmatic proposals presented for these sites are naive in their political feasibility. Yet, one hopes that such projects would err on the side of optimism, no? When actual city planning officials, residents, and small business owners were involved in selecting sites and hosting project visits, overt cynicism starts to seem self-indulgent.

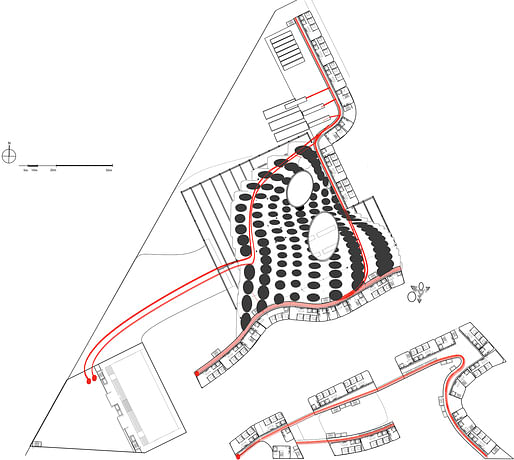

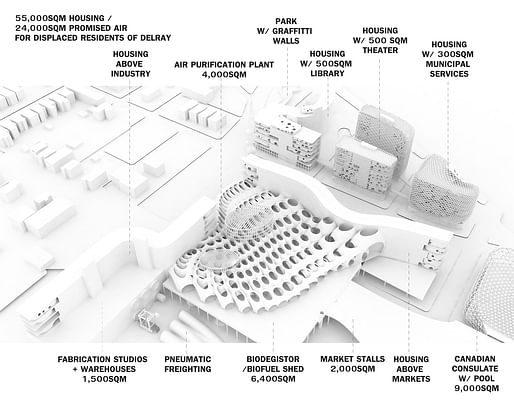

A(n) Office project combining housing with air purification plant, pneumatic freighting, bio-fuel related industry, and the Canadian Consulate.

A(n) proposal for Livernois garage yard in Mexicantown.

A(n) Office proposal, Canadian consulate, housing and industry for more than 250 families relocated by new international bridge.

Existing Livernois Yard / Mexicantown site: Publicly owned lot with existing municipal garage in background.

The US Pavilion aimed for an intensity and density that we are no longer accustomed to in the US for publicly-oriented projects, or that we might associate with luxury real estate (e.g. the Highline). I can understand the confusion here. However, let’s recognize that, perhaps, things are starting to change in this country, as far as the capacity of cities to step up and make significant proposals in the built environment on behalf of their citizens. Look at Los Angeles restoring an entire river and converting itself to a public transportation city. Look at Chicago bringing people to the Riverwalk and starting to clean up its river – which for 100 years no one bothered to clean, since it had been re-routed to flow its filth into the Mississippi River.

Detroit has some of the largest civil engineering works in the country (eg see the largest single-site waste-water treatment plant in the US here), still operating, centralized, and serving millions of people throughout the Detroit metro area. When we look at speculative projects sited in Detroit and dismiss their scale, density, or exuberance as incongruous with the context, I wonder what context we are assuming. With all due respect to the Rural Studio’s brilliant, elegant work in Mobile Alabama—Detroit is no Mobile, Alabama. Many Black Americans moved to Detroit from Mobile, Alabama and Southern towns like it during the great Migration exactly because it is not Mobile Alabama. It is a city with major international trade, an international border, large research universities, and sprawling, capitalized institutions and infrastructure. Are we so accustomed in the world of architectural criticism to assuming a white public that we regard any majority-Black city as hopelessly mired in poverty and left to build itself out of rammed earth and discarded household garbage? I am highly disturbed by the subtext that some cities might participate in imagining their futures on a transforming planet, while some cities just chug along in a kind of entropic banality. To the extent that the latter does happen, it is through the kind of well-financed New Urbanism that dominates the public’s engagement of architecture at a local level, while those of us meddling in the global field do a terrible job of discussing our work back home.

A GLIMPSE OF WHAT AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE MIGHT OFFER THE WORLD TODAY

As far as what the USA has to offer the world in architecture – a question brought up in Architect Newspaper’s review - more crucial than ever might be how to densify cities within a paradigm of multicultural democracy, across a variety of ecologies and socio-economic situations. More specifically, many large metropolitan regions around the world need to explore how to shift away from the fossil-fuel-heavy suburban model along a path that creates more equity and restorative justice, rather than driving up income inequality and environmental racism.

Housing is key to this. Amidst the repeated fiasco of capital market models for housing in the US (see this recent NYT article on private equity), it would be negligent for those of us working in the built environment to not support some exploration of an alternative model of urban housing. The US Pavilion is, quietly, full of housing-- from Present Future for the Post Office, Zago Architecture for the Dequindre Cut, to our A(n) proposal for the Livernois Yard site in Mexicantown. These are the 3 sites with majority public ownership. On the privately owned Packard Plant, SAA/Stan Allen Architect proposes a small ratio of live-work housing embedded within botanical gardens.

If we are to discuss realism, also relevant are the policies and planning of density in American cities. In Detroit, there is a new 5-year public transit plan for the metro area, which requires certain levels of density to be fully viable in the long-term. As planners know well, transportation, jobs, and density operate in a kind of feedback loop. The goal of this 5 year transport plan, one would hope, would be to serve the existing population of Detroit and connect to new jobs. *Existing* residents and *new* jobs. We can see density emerging from not only new residents (problematic) but primarily new work opportunities (completely necessary and feasible in Detroit and not at all requiring large corporations). Industrial jobs still exist in Detroit, as do the skills for them. This reality appears in proposals for the Packard Plant, as well as our A(n) Office project with industrial spaces for freighting and bio-fuel related industry.

There is also the effect of land prices. If architectural criticism projects a political economy onto abstract proposals, I am all for that. But let's be a bit rigorous about that political economy. In New York City the land prices are about $1,000 a square foot. So you build multiple levels - lets say 5 FAR—10 stories on half the lot gets you to $200 per sq ft of land cost. If construction costs even $400 dollars a square foot (low end of the average in NYC) you are quickly at $600 sq ft total cost, before a developer even makes a profit or pays the design team, re-mediates a site or does any amenities. It is no wonder the market builds luxury upon luxury there, feeding an endless cycle of scarcity.

For all the fetishizing of "Africa" going on in this Biennale, let's get rigorous about what local materials mean in a hyper-active industrial context. When half a million tons of concrete are mobilized for a new piece of international infrastructure, that becomes a local material. The trucks are deployed, the mixers, staging ground. How do we treat such temporary infrastructural deployments as major shifts in material and labor flows that our architecture can operate with, so that we are not planning buildings, but planning flows of material and technology? This is what the A(n) Office project hoped to open up, and I think a number of the projects. Our proposal was, undoubtedly, cloudy about such issues, but one hopes that’s what decent criticism can help unpack. (Silly me, I forgot to check www.decentarchitecturecriticism.org...)

WHY DETROIT MIGHT BE IMPORTANT FOR THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE

Detroit presents an alterity to the logic of scarcity-- so much so that it makes us think another mode of city making is possible. What if land were available to the public, surrounded by an industrially-skilled local labor force eager for substantive employment? This doesn't even sound real in American architecture! We are used to focusing on cities where land has been turned into a commodity and the labor force is tight and service-oriented.

When the local labor force has experience in raw computer programming, mechanical engineering, welding, and even robotics, but no skill in standard construction -- Upon what logic does it become cheap and sensible to build standard construction? Only a logic that privileges large business, actually, in the form of national construction management companies. Or a logic that wants to repeat the fabric of single family homes that's already here, an anti-urban, anti-density position, far too common in the US. My hope is that Detroit can resist the banality of strip malls and corporate-funded suburbanization, and it might take something other than American-architecture-as-usual to make that possible.

Detroit is an anomaly. It is changing - because that’s what cities do, not because it’s being saved, or rescued, or because it reached some financially recognizable nadir. The Detroit that I have come to know over the past few years might evolve into something this country has never seen before -- a city full of homeowners and renters who own plots of park-communes, collectives built from the patterns of the single-family home but not tied to its initial property claims. Or an Afrotopian city that maybe is already here, waiting to be revealed. Such a city would, hopefully, be supported by the kind of density that can enable a new public transportation infrastructure and new forms of work.

At the end of the day, the actual client for the projects at the US Pavilion was not the City of Detroit or its residents, but the US Department of State, through a series of experienced sub-contractors. All these projects, or maybe just ours at A(n) Office, are actually speculative embassies of sorts -- architectural machines for this terrified, traumatized, expansive country to encounter itself.

Posts are sporadic. Topics span architecture, urban design, planning, and tangents from these. I sometimes include excerpts of academic articles.

2 Comments

Yes!

Beyond its obvious bells and whistles, one can consider the Biennale to be a pseudo-leftist endeavor that seeks to reconstitute and legitimatize the existing power structures that are responsible for our contemporary entanglements as such. This platform has enabled firms like Foster believe that they can be controversial within certain limits to create enough momentum that creates no change in the existing paradigm but instead seeks to reestablish the established. An absolute recoil, if you ask me. If an architect wants to address an issue specific to a location, the architect should take his/her intervention there and stop parading it at the Biennale for some emphatic response. Look at Adeyemi's intervention in Lagos, Nigeria. The building collapsed. Really!!!! (As a Nigerian, I believe we should call what it really is, not label the occurrence as some unfair force majeure that disrupted good human endeavors).

Concerning the issue of poverty and architecture, we architects have to understand that at its very core lies politics, economics and socio-cultural discourses that need to be addressed. We have to either join the table of discussion or we stop using the idea of poverty for our own selfish gains that only exacerbates the matter. Only design for the poor when the economic and political climatic conditions of a place is habitable for the poor… WE NEED TO STOP DECEIVING OURSELVES. Lastly, in the words of Simon Springer, FUCK NEOLIBERALISM. FUCK NEOLIBERAL ARCHITECTURE.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.