The controversial plans to demolish the American Folk Art Museum in service of MoMA's expansion rumbled along last night, at a panel discussion hosted jointly by the Architectural League, the Municipal Art Society, and the AIA's New York chapter.

Catch-up on news surrounding MoMA's expansion here:

Archinect contributors / Parsons MArch students Ayesha Ghosh and Alex Stewart attended the event, taking notes and logging thoughts. The following is their report.

* updated February 3, 2014: You can also find a video of the entire discussion, courtesy of the Architectural League, at the bottom of this post.

A Conversation on the Museum of Modern Art’s Plan for Expansion

Ayesha Ghosh and Alex Stewart reporting, January 28, 2014.

This evening, the Architectural League of New York, the Municipal Art Society, and the AIA New York Chapter hosted a conversation on MoMA and Diller, Scofidio, + Renfro’s plan to demolish the Folk Art Museum amidst plans for expansion. Held at the New York Society for Ethical Culture on Central Park West, the audience listened to a presentation by Elizabeth Diller, a panel discussion moderated by Reed Kroloff, and an audience Q&A session. Boxing gloves, however, were kindly requested to be checked at the door.

The night began with a brief welcome by Annabelle Seldorf, President of the Architecture League, who called for decency and civility in the discussion (laughter ensues). Vin Cipolla, President of the Municipal Art Society, and Lance J. Brown, President of AIA NY, each gave a brief shout out to the sponsors, leading to the introduction of our moderator for the discussion, Reed Kroloff (Director, Cranbrook Academy). Kroloff again made the plea for thoughtful and respectful conversation, and reminded the audience why they had gathered: the fate of the American Folk Art Museum, and the future of MoMA. Also, that everyone in the audience was missing the State of the Union address…

Kroloff introduced the first speakers: Glenn D. Lowry, Director of MoMA, and Anne Temkin, Chief curator of Painting and Sculpture. Lowry started by acknowledging the common criticisms of MoMA, that is, being large, monolithic, and insensitive. He countered these preconceptions by explaining that MoMA is not only self-critical but also focuses on making the museum better for the public. Inherent in that is the plan for campus expansion, which includes 30% more exhibition space and the opportunity to engage the public in new ways. He identified three questions to be addressed:

1. How could an institution like MoMA not preserve a museum like the Folk Art?

2. Why does MoMA need to expand at all?

3. Is there no way to incorporate the existing Folk Art Museum in the expansion?

Lowry answered the first question by saying they really tried, hard, but there was no possible scenario in which the Folk Art Museum could be preserved while still meeting the growing needs of the museum. He passed the torch to Ann Temkin, representing the curators of MoMA to explain how the expansion was necessary to continue the good work of MoMA, essentially hitting their bullet points laid out in the New York Times article from January 18th. Temkin explained that given the breadth of their collection and their responsibility to show both canonical and more contemporary modern art, increasing is a necessity. Comparing MoMA to Florence in the Renaissance, she elucidated that MoMA is a catalyst for contemporary artists, not just a museum for their work.

Liz Diller took the podium with a palpable tension in the air, and immediately addressed it with a joke that the nicest remark she’d heard recently was how brave she was for attending tonight’s event. This was shortly followed by an acknowledgement that the teenage Folk Art Museum was not a historic building, and that even if no minds were changed during the night’s event, hopefully there would be more appreciation for DS+R’s process. Diller identified two reasons for accepting the project, one being the original belief that the Folk Art Museum (FAM) could indeed be saved, and that despite being critics of MoMA themselves, they believed in MoMA’s mission for expansion to work across disciplines, improve circulation, and create a strong interface with the city. But, the building is an organism, and adjusting one portion affects everything. “Adaptive Reuse” became the battle-cry for the mission to retain the character and unique features of the FAM, pushing MoMA for a reduction in their program requirements, but they realized over time the building simply will not fit the gallery requirements of MoMA.

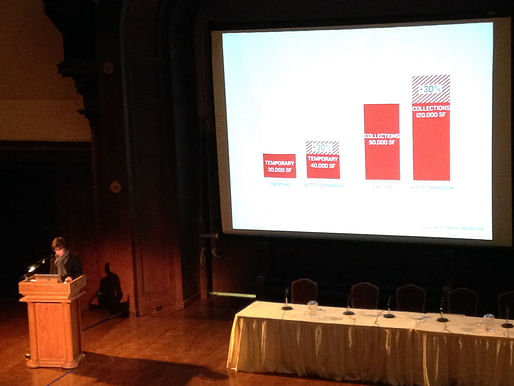

Issues included misaligned floors that, if retained, would create awkwardly sized spaces that were difficult to use, a reduction of natural light after the central skylight was removed for mechanical on the roof, and a prosthetic façade (reattachment after necessary demo and reconstruction efforts); all cementing the realization that the FAM would be a shadow of its original building. Diller lauded the building’s resistance to change as one of its strengths but noted that the expansion was an intensive surgery of the entire MoMA campus that could not accommodate the bespoke nature of the FAM. The new museum will create a circulatory loop between galleries, increase the number of entrances, incorporate larger exhibition spaces, and bring experimental art spaces onto the street. Equally important—and not explained in the NY Times release—was the need for a new vertical core which, in its most convenient and least invasive location, occupied the entire rear of the FAM. Diller then showed a series of slides detailing how much more space there would be gained throughout the museum for art, but left the audience with a simple plan drawing, reiterating that the project is very much still in the process of design. She did, however, leave with an intriguing caveat that DS+R would attempt to show vestiges of the past buildings throughout the MoMA campus, including the FAM.

Kroloff then resumed his role as moderator, and introduced the diverse panel of the New York architecture scene, in alphabetic order. No preferential treatment here. Cathleen McGuigan (Editor-in-Chief of Architectural Record), Jorge Otero-Pailos (Associate Professor, GSAPP), Nicolai Oroussoff (writer/critic), Stephen Rustow (Principal, Museoplan), and Karen Stein (architectural advisor) took their seats. Kroloff dived right in by asking Otero-Pailos why the public has the right to talk about what MoMA plans to do with the FAM. Otero-Pailos points out that MoMA is cultural space, the public can raise conversation about the nature of architecture because it affects the quality of the city. He said the city is defined by qualities, not quantities.

Following on this answer, Kroloff asked McGuigan what is good for the public? McGuigan points out that MoMA depends on the public, and noted the emotional place the FAM took in [our] lives following its opening a few months post-9/11. The opening was an incredible coming together, and won many awards during a period when New Yorkers felt strongly about the city.

The next question, aimed at Rustow, asked whether the decision to demolish FAM was a failure of the original architecture or a failure on the part of MoMA’s new architectural plan. Rustow remarked that it is churlish to assume FAM could anticipate the future, and took issue with the use of the word ‘failure’. He gave Diller and DS+R credit for exploring feasibility studies, and acknowledged that the FAM has to go; however, he advocates for the possibility of retaining portions of the existing structure.

Oroussoff jumped into the conversation by pointing out that while FAM has a cultural history, MoMA’s responsibility is to its collection. To a sea of gasps, he noted that FAM is not a Mies or a Kahn, in which case this conversation would never be up for discussion. He noted that like many other museums in the city, the FAM is flawed and difficult to display art within (New Museum, 2 Columbus Circle). He argued strongly against facadism, in line with Tod Williams Billie Tsien’s opinion. Kroloff quickly chimes in to ask Oroussoff whether he was straying into dangerous territory by creating a rank order and set of values. Oroussoff reminds crowd that as a critic he can’t say that setting standards is a matter of personal decisions (laughter), instead while FAM has historical value, it doesn’t fit with MoMA’s standards, and lastly no one in the crowd seemed to be complaining about alterations to the Taniguchi building.

Kroloff: Fair enough.

Karen Stein entered the conversation at this point, raising the question of priority and framing of the problem for MoMA (and DS+R). She compared the design process to a mathematical theorem where each solution unfolds a separate problem, and her issue laid in the initial problem, which is, in her mind, the closed loop. If you commit to circulation as priority, it leads down a slippery road where the eventual decision to demo FAM is necessary (resounding ovation).

Kroloff asks Stein if MoMA has a specific responsibility to the FAM as an art collector. Stein firmly states that MoMA has a responsibility to the discipline of architecture in the same way it does to art.

Otero-Pailos interjected by claiming MoMA has a responsibility to the discipline but not to the preservation. He advocated rethinking preservation on a whole, and reminisces on the olfactory difference between the FAM and MoMA, recalling the former’s signature scent, and how the latter recalls an airport.

Rustow followed by dismissing facadism, saying that TWBT’s on record disapproval is irrelevant. He referenced multiple global works where facades were retained and interiors were adjusted to new uses.

Kroloff moved the conversation forward with a question directed toward McGuigan, asking where the architect’s responsibility to the client ends, and where it begins with the city. McGuigan notes that this is an unusual situation as the client is an institution, and gives props to Lincoln Center for showing how there can be more than one approach to repurposing a building.

Oroussoff is back. He reiterates MoMA’s dual responsibility to architecture and its collection, but asks what are their priorities and who is the target audience. He references the DS+R plan to enhance entries to the galleries, and proposing using FAM as one of those entry points.

Kroloff wrapped up the panel discussion by asking for concluding comments from each member. Rustow laments that the treatment of the project in the press has been most regrettable. Stein gives an impassioned speech calling out the collision of MoMA’s missions, quipping that she would expect Wal-Mart to tear down FAM, but not MoMA. “If FAM had a Richard Sera, would MoMA tear that down?” she asked rhetorically. She berated the use of bespoke as a ‘bad’ word, and said, “I thought great architecture was made to measure.” Otero-Pailos postulated into the future, asking that in 15 years, when MoMA is ready to move, what will be left? Oroussoff took the conclusions to a broader level, stating the bigger issue is the system, wherein the public is invited to the forum too late. Lastly, McGuigan was simply concerned with the speed of the process; that the building would be torn down sooner than she expected (June).

Kroloff invited Diller, Lowry, and Temkin to join the panel on stage, in order to begin answering queries collected from the audience. The first question came from “Daisy”, who butchered a “Corb” quote about trying harder when at first you don’t succeed. Lowry claims the design team tried their hardest, and worked through a lot of options. The next question, also aimed at the MoMA representatives, asked why the museum could not expand elsewhere? Lowry confirms constant consideration of that matter, but that MoMA celebrates history, and that the museum does not want to fracture their collection. Temkin stepped in to point out that PS1, referencing again the current Mike Kelly show, is the experimental space for MoMA, and the main museum requires a unity of place. Diller chimes in to address the Oroussoff comment regarding FAM as point of entry, driving home the point that they tried everything. She explains how that strategy would bifurcate the audience, into New Yorkers exploring new exhibits and tourists visiting the classics. Stifled to enthusiastic applause ensued, to which Kroloff reprimanded the audience for being xenophobic monsters, and to please, control themselves.

The next question asked whether vertical exhibition was considered over horizontality. Diller stated, “I hate to be the logical one”, and pointed out that horizontality is necessary to create a narrative and chronology. She stated that DS+R would not take the commission if they could not create successful galleries.

The next question brought Landmark Status of contemporary buildings to the forefront, asking if city laws should be amended. Otero-Pailos simply responded ‘yes’, they should be revised, but not in this instance.

“Idiosyncrasy, inefficiency and expense were the reasons cited by developers who wanted to demolish the Highline, and they were wrong. Does a cultural institution have a special rationale, or perhaps a special obligation, for valuing idiosyncrasy, inefficiency and investment that the private sector may not?” asked Vishan Chakrabharti. Kroloff quipped “and the book is on sale.”

Diller claimed DS+R stands for all of that, noting they have a complicated role in this, and that “bespoke nature” is a good thing. However, she stated that it becomes a question of trying to do something next without becoming paralyzed by what already exists. The whole ordeal became an ethical problem. Diller complimented MoMA by mentioning their ambition of relating to the public, and hoped that there will be a public forum to advocate for their work in the future. She admitted, however, that we have no control over the future, that futures change constantly, that clients abandoned the FAM and it now sits fallow. It was truly an emotional response, that concluded to the audience that the building was irreconcilable for the future of MoMA.

The last question was directed back at Lowry, and asked point blank, why do you treat architecture differently than art. Lowry responded, eloquently, that architecture is different from painting and sculpture, referencing the process and purpose specifically. “We don’t collect buildings,” he said. Architecture’s purpose does not exist as an autonomous object, he stated, as the FAM replaced a beautiful brownstone in midtown before it’s construction. “Architecture raises a completely different set of questions, and engenders a different set of responsibilities.” He concluded by saying that preservation exists to provide function to out of use buildings.

A spirited response indeed, but it begs the question, why can’t MoMA retain portions of the building for preservation?

That final answer by Lowry concluded the evening’s events. A full video will soon be available online through the Architectural League website. Thanks for reading.

- Ayesha Ghosh and Alex Stewart

10 Comments

"Here, take this deposit to the bank."

I don't understand why they even pretend to care what the public thinks. Its one thing to tear down the FAM but its another thing to replace it with that generic condo type building

What a great rhetorical ballet. Here are some of the hightlights...

Comparing MoMA to Florence in the Renaissance, she (Temkin) elucidated that MoMA is a catalyst for contemporary artists, not just a museum for their work. Except that the Moma's founding was diametrically opposed to the nature of the Renaissance in Florence.

To a sea of gasps, he (Oroussoff ) noted that FAM is not a Mies or a Kahn, in which case this conversation would never be up for discussion. I'd love to hear the full list of Gods the Moma would consider beyond reproach.

Diller then showed a series of slides detailing how much more space there would be gained throughout the museum for art, but left the audience with a simple plan drawing, reiterating that the project is very much still in the process of design. 'We'll slap on an elevation once we get there' as if the plan and elevation where divorced. How modern!

She did, however, leave with an intriguing caveat that DS+R would attempt to show vestiges of the past buildings throughout the MoMA campus, including the FAM. Intriguing indeed since they professed to abhore facadism. How about vestigism?

The next question, also aimed at the MoMA representatives, asked why the museum could not expand elsewhere?...(Diller chimes in) She explains how that strategy would bifurcate the audience, into New Yorkers exploring new exhibits and tourists visiting the classics. Stifled to enthusiastic applause ensued, to which Kroloff reprimanded the audience for being xenophobic monsters, and to please, control themselves. Got it.

The last question was directed back at Lowry, and asked point blank, why do you treat architecture differently than art. Lowry responded, eloquently, that architecture is different from painting and sculpture, referencing the process and purpose specifically. “We don’t collect buildings,” he said. Architecture’s purpose does not exist as an autonomous object, Since when did modernism think of buildings as anything other than objects?

“Architecture raises a completely different set of questions, and engenders a different set of responsibilities.” He concluded by saying that preservation exists to provide function to out of use buildings. Now we see that the art of architecture is completely dead. Whatever "function" the FAM served can only be understood as space container, unlike the "canonical" works inside that preserve our cultural memory. The preservation of buildings only qualifies if it contributes directly to the bottom line, ie. the role of Florence in the Rennaisance.

Bravo!

Having looked at the coverage here and on archidose, why couldn’t the circulation loop at the rear of or just behind the FAM and why couldn’t the mechanical spaces be placed in the tower?

Also, Elizabeth Diller is mistaken; a narrative and chronology can be created in a vertical format.

A few comments:

- Why would the skylight need to be closed to place mechanical equipment on the roof? This is one of those ARE-simple problems: if there's a skylight on a roof, you place the mechanical equipment somewhere else. Architects do it all the time.

- I'm wondering if Kroloff asked Otero-Pailos "WHY does the public have the right to talk about MOMA?" or "PLEASE EXPLAIN why the public has the right...?". If it's the former I am unpleasantly but mildly suprised that he would ask a question so well-designed to put Otero-Pailos on the defensive to have to reaffirm something so basic: everyone's right to speak about public built space. I was in a Zoning Board variance hearing last week - this right is common and built into our society. Would Kroloff pretend that it's not?

- Orousoff's question is off: he shouldn't be asking whether the FAM is a Mies or a Kahn but rather whether TWBTA as architects are Mies or Kahn. I think 50 years from now the history of architecture will show that they are, but if we tear down all their buildings first we'll not have the benefit of experiencing them to be sure. Sort of like John Soane - basically one masterpiece still exists; the loss of all his other work deprives us all of his brilliance.

- The reason no one is complaining about DSR's alterations to the Taniguchi building is that it's not very interesting as a building. The architect himself said so in his famous quote that he could "..make the architecture disappear". He succeeded, but making the building disappear was never a goal in the FAM.

- Lowry says they don't collect architecture, because architecture doesn't exist as an autonomous object. Um, neither does performance, which is what the new Art Bay will house, yet MoMA fully intends to collect it, despite the difficulties.

Vishan Chakrabarti's comment is right on. Art is difficult, contemporary art especially. As I've said elsewhere, part of why we value art is that it's outside of everyday convenience. Good art causes us stress, in a good way - it puts us in a liminal space that makes the everyday more enjoyable/bearable by contrast. The FAM could do that too.

Ayesha and Alex, thank you so much for this wrap-up!

My first question: WHO INVITED OUROUSSOFF? I wonder if Lowry promised him something ...like a magazine of Frank Gehry architectural moneyshots.

The issue that was lost (to Ouroussoff, Lowry) is that what makes NYC vibrant is the grid, (an idea explored in Delirious NY) allows for multiple variations. I actually like Taniguchi's MoMA and the FAM separately. The issue is when the MoMA starts to grow like a virus, homogenizing the area. The same issue would work in reverse if the FAM was steamrolling the MoMA (imagine that!).

And lastly, that DS+R rendering of a saved FAM making the rounds actually looks quite DS+Resque. My guess is that MoMA told them behind closed doors to get rid of the FAM or lose the project. There really is no other explanation.

No it isn't a Mies or a Kahn. Apparently, it is a Yamasaki. The FAM is the Pruitt-Igoe of Museums.

im the Pruitt-Igoe of my family.

I get so tired of talking asses....oops I mean people talking out of there asses...now what was that smell. DS= "well" Dog... i will keep you guessing.

Here is an excellent example of a deeply indiosyncratic building that shows art beautifully.

Zumthor's Kolumba museum of Diocesian art

Interwoven forms of very old, kinda old, and new, but all of rich and contrasting materials, blended in very spatially complex ways, and showing art on the floor, grouped salon-style, in niches, on funny old tables...basically not forcing art to submit to the homogenization of evenly-spaced 60" center mount on a diffusely-lit plain white wall. It looks like an incredible experience, and far more transformative for the viewer than an airport-smelling enormous white box.

I'd put TWBTA in the same category of genius as Zumthor.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.