Archinect is delighted to present 5468796 Architecture's travelogue for their award-winning research project, Table for Twelve. The Winnipeg-based firm received the 2013 Professional Prix de Rome in Architecture from the Canada Council for the Arts, awarded to emerging Canadian architects with outstanding artistic potential. The $50,000 prize will support the firm’s worldwide travels to both strengthen their skills and expand their presence within the international architectural community.

5468796’s Table for Twelve will hold dinner parties at architectural epicenters around the world, in the hopes that picking the brains of local talent will help them identify the drivers behind a strong design culture. Archinect plays host to their global dispatches through this travel blog, updated upon each city’s dinner.

From 5468796:

DINNER

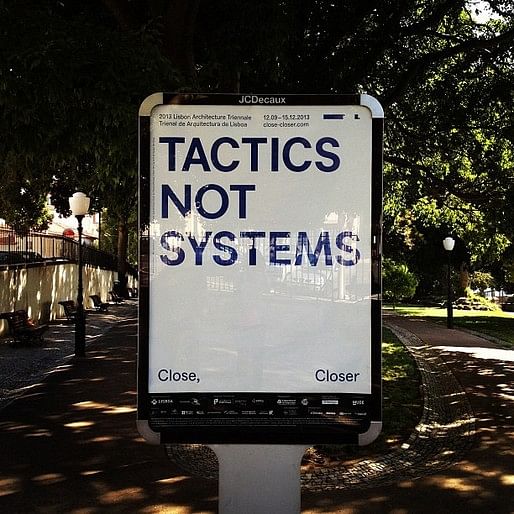

The first installment of the “Table” in our year-long research project was held in Portugal during the opening week of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale. The dinner proved to be an amazing and somewhat surreal evening that delivered many memorable moments and fruitful conversations shared by Portuguese architects, journalists, members of the Triennale, Canadian architecture students and ourselves.

The stage for our first dinner was masterfully set within the framework of The Real and Other Fictions, an exhibition curated by Mariana Pestana for the Triennale in the spectacular 16th century Pombal Palace. Occupying an unassuming position on Rua de O Século, the building currently houses Carpe Diem Arte e Pesquisa, a contemporary art institution and research facility. The Palace’s many past lives (including former home of the Spanish Embassy) were the curatorial theme of the exhibition, with each room representing a different point in its impressive history.

One such room was occupied by the creators of our meal, the Center for Genomic Gastronomy, a Portland-based research institute that examines the intersection of food, culture, ecology and technology. Against a backdrop of faded grandeur, their dinner event, The Planetary Sculpture Supper Club, promised to deliver a curated culinary experience aimed at challenging our outlook on life and food through our sense of taste – as well as touch (as we later discovered).

The setting for our meal was a gorgeous vaulted space with an enormous mirrored hexagonal table placed directly in the centre, reflecting the ornate ceiling and eventually our curious faces as we sat down for dinner. We were soon told that we would be eating with nothing but our hands, and were then invited to wash by a server who ceremoniously poured water from a clay pitcher. Once we had cleaned our hands and found our seats, all of our iPhones came out to try and capture the moment. Our host then arrived to explain the dinner, its progression and its attempt to slow us down and consider the pace of our world along with the impact this has on food sourcing, production, consumption and ultimately on society. We confronted this reality with each course as we bent over to see ourselves eating food primitively with our fingers, the reflected ceiling mural acting as our tablecloth.

Within this incredible sensory experience the discussion around the table moved through many topics including the dinner itself, the venue, the Portuguese economy, the culture of architecture in Portugal past and present, as well as the implications of Siza worship, but always seemed to come back to “what will be eating next?” and “. . . still with our fingers?”

We found the conversation to be filled with Diogo Burnay’s contagious optimism, Luis Pedra Silva’s brash skepticism, Pedro Belo Ravara’s stubborn belief in Portugal, and the probing nature of the journalists present. There was an overarching sense of hope in Portuguese architecture as well as the general belief in the potential for design and architecture to affect change.

Regarding the optimism found in Portuguese architecture culture, it was believed to have emerged from a long-standing tradition of resilience and resistance, resulting in something that is used to standing up for itself and has the strength necessary to endure the forces of social pressure and the current economic crisis. If left unchecked, these forces can erode the foundations of a design culture, leaving it unable to speak meaningfully and critically to a larger arena.

The question was then asked: how do architectural practices provide this important cultural voice, while being primarily a private enterprise with its own survival of paramount importance, and often dependent on the exact culture it wishes to change?

As an architectural journalist, Brendan Cormier suggested that understanding each practice’s survival tactics allowed him to cut through most of the bullshit we spin, in order to get at what matters to us. His theory was that when firms describe how they survive, they unveil their basic instincts, and what they – or their architecture – needs to live. This thought generated a vigorous debate around the table as to its validity, and what in fact each of our survival tactics were. Regardless of the answer, it was one of the lingering questions from the Lisbon dinner that warrants further thought.

Questions that flowed from this conversation included: how do we build resiliency as a firm, a design community, a country? What are we to learn from the great architects, and to what reach is their impact? How do we move beyond disciplinary relevance into a greater cultural or social significance? And perhaps the most important question, do we really need eating utensils?

The dinner itself promised to be memorable and it did not disappoint. From the amazing flavours in the salad first course, to the visually striking deconstructed fish plate with a traditional Portuguese sardine as the star of the evening, to the affronting course of diced pig ear and fried pig tail (served in an actual pig’s ear), and finally to the dessert offering a sweet, fruity, and sloppy ending to a wonderful evening, we shared a meal that none of us will soon forget.

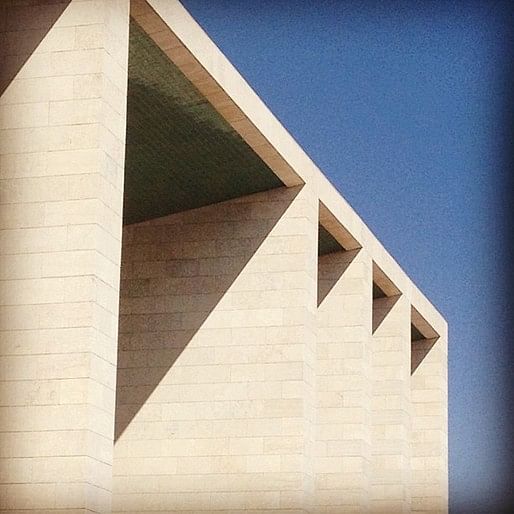

The day after our dinner (and a surreal nightcap on the roof of a parking garage in the pulsating Bairro Alto district), we hopped in a cab for a sort of pilgrimage to Álvaro Siza’s Expo 98 Pavilion. Along the way we chatted with our driver about what we were going to see, and we discovered that he hadn’t heard of Siza. He took the opportunity instead to point out the “most beautiful buildings in Lisbon,” which coincidentally were right across the street from the pavilion: a pair of luxury condominium towers with shark fin-like appendages on their roofs.

The episode left us thinking that perhaps Portugal and Canada are not so different after all, and that the challenges we face in Canada of creating a design culture are not so different from the challenges of maintaining and growing architectural appreciation in areas with long-standing traditions of valuing and promoting the importance of design.

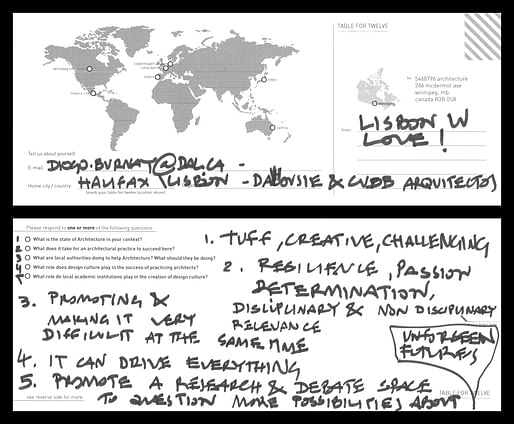

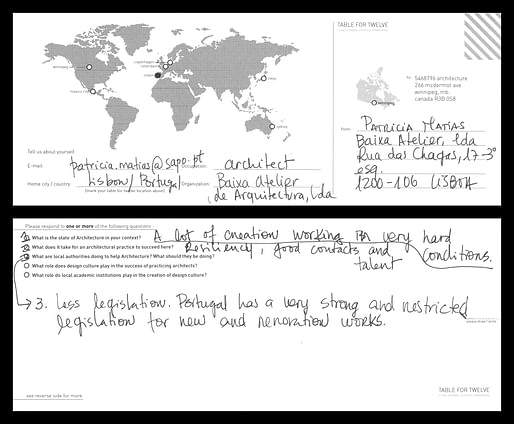

TABLE FOR TWELVE POSTCARDS

In each city we visit, we will be collecting postcard responses to a series of questions related to architectural culture. These cards serve as both a memento from our dinner guests as well as a means with which we can compare different design contexts.

Our questions are:

• What is the state of Architecture in your context?

• What does it take for an architectural practice to succeed here?

• What are local authorities doing to help Architecture? What should they be doing?

• What role does design culture play in the success of practicing architects?

• What role do local academic institutions play in the creation of design culture?

IMPRESSIONS

We land at 6am the day before the opening of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, the collateral event that has led us to the city for our first Table for Twelve meal and discussion about the state of architecture culture in Portugal.

On almost no sleep we venture out, first in search of coffee and second to find the headquarters for the Triennale. We are struck both by Lisbon’s unassuming beauty and by its topography. Making the transition from flat Winnipeg to a city of hills – seven, to be exact – proves to be a physical challenge and ongoing topic of conversation: “Is it uphill? Can we walk around the hill? Can we go downhill from here? Maybe we should take the trolley.”

After an hour long walk filled with countless iPhone snapshots, we come to 142 Campo de Santa Clara on the edge of the Alfama district. Behind the unmarked door of a seemingly vacant building lies an explosion of architectural energy in a gorgeous and crumbling former palace. People are crammed into every corner of century old rooms, working frantically to put the finishing touches on a fraction of the over 100 Associated Projects that will become part of the Triennale during the next three months. Amidst the chaos, the young group pulling off this world class event on a shoestring budget appear relatively unfazed and endlessly optimistic. Our guide, Rita, offers a breathless summary of the exhibitions on offer during opening week, and then we head off (thankfully downhill) to check in to our apartment.

Our second evening in Lisbon is full of Canadian references amidst truly Portuguese experiences. First we watch Jimenez Lai – a Taiwanese-Canadian transplant in Chicago and principal of Bureau Spectacular – receive the inaugural Triennale Millennium BCP Début Award in front of a packed auditorium following the opening of the Future Perfect exhibition in the Electrical Museum. Second, we at long last shake hands with the whirlwind known as Diogo Burnay, Director of the Dalhousie University School of Architecture in Halifax, principal of CVDB architectos in Lisbon, and an invaluable contact for us in the time leading up to our trip.

After the opening, we hop in Diogo’s car for what becomes an unexpected cultural and culinary tour of Lisbon, including a snack of pastel de nata at Casa Pastéis de Belém, the city’s oldest and most famous pastry shop that serves upwards of 11,000 egg tarts a day; a drive-by tour of the Belem Cultural Center and the Jerónimos Monastery; a crash course in which port to buy (they’re all good, but vintage ports must be drunk in a few days); and finally a slice of pizza at Pizzaria do Bairro, a brand new restaurant run by an architect / landlord / chef who is making reinvented Portuguese-themed pizzas (the margherita becomes the maria) in a building shared by his architecture studio / nightclub. We eventually meet up with two of Diogo’s students from Dalhousie who are living in his apartment in the Bairro Alto and attending FAUTL on an Erasmus Exchange. These students also happen to be winning participants in a competition for Arctic Adaptations, Canada’s official submission to the 2014 Venice Biennale in Architecture, an event that our office co-curated last year.

The streets are incomprehensibly busy, with people occupying every available inch of space for blocks on end in an entire city district. Crowding together in one of thousands of small bars in the city – we learn that this year 26,000 restaurants in Lisbon are expected to close due to the economic crisis – we have our first shot of Ginjinha in a chocolate shooter bowl, followed by our first shot of Licor Beirão, two Portuguese institutions that we could not have gone home without sampling at least once.

During our time with Diogo, we quickly discover that someone who has the endurance to travel back and forth between Portugal and Canada every month simultaneously running an architecture school and practice has the energy to stay up all night on only two hours of sleep. At 2am we leave the trio in Camões Square, going to bed much earlier than the rest of Lisbon in preparation for our Table for Twelve dinner the next day.

Although it is difficult to draw concrete conclusions about any city in a short time frame, throughout our stay we were struck by the optimism, energy, graciousness and humility of the people we spoke with. Despite – or perhaps as the result of – living in a country that has the highest unemployment rate in the EU, there is a pervasive do-it-yourself, make-something-from-nothing attitude and emphasis on resourcefulness that was extremely inspiring for us.

There is also an incredibly strong sense of pride in both the country’s architectural history and its future, however uncertain it may be.

In addition to being the birthplace of two Pritzker Prize winners, Portugal has also produced legions of young architects (73% of architects are under 40), many of whom are seeking work outside of the country or reevaluating their role if they choose to say. A recent article in Blueprint identifies the beginning of a fundamental shift in how young architects are practicing:

“In a counter-move fueled by the crisis, the past two years have seen a rise in the formation of small, experimental studios that seek alternative ways to practice architecture. Their founders are young, motivated, well-educated; many have lived, studied and worked abroad . . . Their work is fundamentally small-scale . . . but their methods offer glimpses of what could be a systemic change, offering living proof that even a crisis can precipitate opportunities for civic engagement and the profession.”

At the same time, in a 2012 poll by the Architects’ Council of Europe, 59% of architects in Portugal responded yes when asked whether they were considering cross-border work. The longterm impact of this migration abroad and renewed sense of civic responsibility at home remains to be seen, but based on the conversations we had it is clear to us that Portuguese architects have the resourcefulness to transform this tenuous and challenging period into positive change.

“Until I’m dead, I’ll keep believing” Diogo says – and we believe him too.

More travelogues from Table for Twelve | Lisbon:

Interview: Luis Santiago Baptista

Interview: Pedro Belo Ravara

Interview: Jose Mateus

A full list of dinner guests and contributors can be found here.

A complete selection of records from Table for Twelve | Lisbon can be found on 5468796 Architecture's website.

2 Comments

Fantastic. What a great way to gather thoughts on architecture and culture! Dinner parties have been expansive educational experiences in my life, going back to Cranbrook when we would have visiting guests join us at the conference/dinner table and forward to now when I try to bring creative people from various fields together at my own house. Food is such a great connector, and a design topic in its own right, so gathering people to eat rather than sit on a panel discussion is a wonderful idea.

A group of architects throw themselves and their friends a lavish dinner party, and plan to throw 11 more. Tens of thousands spent on food, transportation, and hosting. All of this on the pretext that they will learn something substantive about each nation's state of architecture. Not enough time to be comprehensive, not enough guests to be a survey. How noble of these global architects to eat a deconstructed fish plate for architecture's sake. At least it makes a great photoshoot. Oh architecture, never change.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.