Archinect is delighted to present 5468796 Architecture's travelogue for their award-winning research project, Table for Twelve. The Winnipeg-based firm received the 2013 Professional Prix de Rome in Architecture from the Canada Council for the Arts, awarded to emerging Canadian architects with outstanding artistic potential. The $50,000 prize will support the firm’s worldwide travels to both strengthen their skills and expand their presence within the international architectural community.

5468796’s Table for Twelve is a series of dinner parties held at architectural epicenters around the world, in the hopes that picking the brains of local talent will help them identify the drivers behind a strong design culture. Archinect plays host to their global dispatches through this travel blog, updated upon each city’s dinner.

From 5468796, text by Sasa Radulovic:

THE TRIP

5468796 Architecture’s Sasa Radulovic and Johanna Hurme reflect on the third installment of their Table for Twelve series, where they traveled to Tokyo to meet their dinner host and principal of frontofficetokyo, William Galloway, during Tokyo Designers Week. A full list of dinner guests can be found here.

FIRST NIGHT

[Or how many people live here? It seems that they all live on top of each other.]

The Tokyo Airport is a two hour drive away from our hotel at the Shibuya Station, which is considered to be one of the centres (or downtowns) of the city. Japan is an urban nation, which becomes obvious as we experience endless suburbs on the ride to our destination. When we finally arrive, we realize that we are very lucky to have taken a direct shuttle to the hotel, as we would never have been able to find either of the entrances – a double glass door at street level without a sign, or a vehicular ramp that spirals up to the fourth floor entrance lobby.

Shibuya is one of the most intense environments we have ever encountered – a subway system overlaid by streets overlaid by a regional train system, all swarming with people coming and going. Dressed with intent, however unusual, Tokyo’s street style provides a glimpse into the city’s haphazard and ambitious stylistic democracy. Perceived by a Westerner, the fashion choices vary from conservative black suit and tie to a psychedelic megalomania of pink-everythingness. At first glance, the fashion world parallels the built environment, where we witness programmatic packing and layering going something like this: subway, underground restaurant, Starbucks®, bookstore, Tsutaya regional headquarters, and a tiny rooftop apartment next to a soccer field on the 15th level of the adjacent building. Tokyo is often considered an urban jungle – it is certainly a jungle composed of well-considered buildings.

As outsiders, our preconceived notion is that in Japan everyone considers design an important part of their cultural identity. If we think of electronics, the car industry, or even MUJI’s immaculately designed products, we form a picture of discipline and restraint. These assumptions are challenged when we are confronted by a chaotic but functioning urban environment full of small-scale commercial enterprises with their ubiquitous signage, pachinko (gambling) parlours with their stainless steel-balls currency, and a pervasive consumer culture. Residential areas provide a quiet contrast, with narrow alleys, ambiguous entrances and blurred private-to-public boundaries that create a feeling of ambiguity and indeterminacy.

The view from the 15th floor of our hotel shows a sea of mechanical penthouses dotted by what appear to be parasitic residences, interspersed with sport courts. There is no evidence of restraint, discipline or control, but an attitude towards urbanism that is organic and in constant flux. And yet, when looking at the smaller scale, we see a clear attention to detail. George Kunihiro (dinner guest and principal of T-Life Architecture Collaborative) later explains that the small nick on the edge of cheap plastic packaging that allows us to open it effortlessly epitomizes the Japanese obsession with design.

Immersed in the chaos, on the night we arrive we are incapable of finding a cash machine and we eat some sort of Japanese interpretation of a Western sandwich at the hotel, the only place that takes credit cards.

NEXT MORNING

[Or how we learned that architecture is not cheese.]

We meet with our friend-partner-host Bill Galloway at the Shibuya Station, and head off to Daikanyama by train to meet Fumihiko Maki at his office. Hillside Terrace is well known in architectural circles as the place where Maki started his career and has continued to experiment with a series of small scale, high-end urban buildings for the past thirty years. The built environment is much more ordered here than at Shibuya Station, and the scale of buildings interspersed with greenery is pleasant and unthreatening.

We find Maki’s office about 45 minutes before our scheduled meeting (we cannot allow a Master to wait), leaving just enough time for a cappuccino across the street in a surfer clothing store concealing an espresso bar. Maki’s office is located in a building that is obviously his doing. We are greeted by the receptionist and brought into a nondescript, grey-walled boardroom overlooking a garden. Anticipation is in the air, as neither of us has had a meaningful conversation with a Pritzker Prize Winner before. Are we star struck?

Fumihiko Maki is in his 80s, and apparently he still travels alone. When he walks in, Bill introduces us in fluid Japanese, to which we can only offer our smiles. We wonder what is the etiquette – to bow, to shake his hand? Maki-san quickly dispels our trepidations, offers his hand, and we get to introduce ourselves in English. He appears somewhat confused by our intentions, as we describe our goal of trying to learn how the appreciation of design and architecture in hotbeds such as Tokyo, New York or Rotterdam could be transplanted to Canada, or help us grow the appreciation of architecture back home.

We state how obvious it is for us that the Japanese care about architecture and design. Our first question is about why this appreciation exists. After a long and almost uncomfortable pause, Maki-san dispels our preconceived notions – no, they don’t. According to Maki-san, the Japanese public does not care about architecture, similar to their counterparts in North America. Perhaps, he says – warning us that everything he says should not be taken as the only truth but just an observation – it is the fact that they relate to the act of making an object or a building, and not the architecture itself. The tradition of craft is embedded in the country’s cultural psyche. This comment helps us understand the importance of tradition in Japanese culture, not in the Canadian sense through the preservation of bricks and mortar or some other token of heritage, but rather in the preservation of an attitude towards the built environment.

We spend another hour discussing this and other aspects of architecture. When the conversation returns to Table for Twelve’s mission, we speak about our research, which revealed how the Dutch government identified architecture in the 90s as a cultural export and commodity, resulting in global architectural dominance by the likes of OMA and MVRDV, with Denmark taking the torch in recent years via 3XN and BIG.

Maki-san takes his time to consider, and comes back with the punchline: “Architecture is not cheese! You cannot export architecture, it is not a commodity!”

This statement summarizes the flaws in our perception, and makes our task of finding out what makes design and architecture important around the world infinitely more complex. The difference in how architects and the public perceive the built environment in Denmark is entirely opposite to Japan. Where Europeans look at architecture as a cultural export, the Japanese appreciate it through craft and careful building that is completely un-exportable.

NOTION OF TRADITION

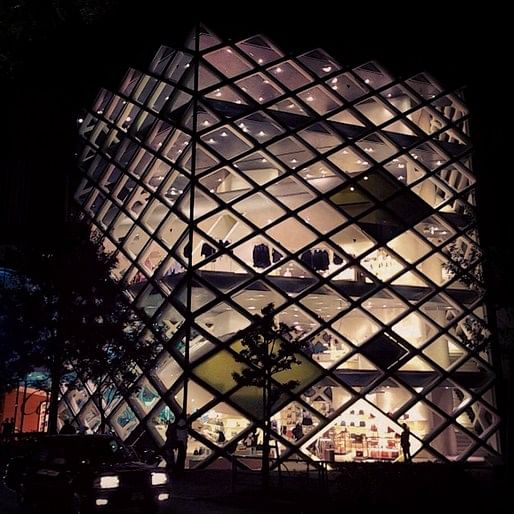

As we leave the office, still overwhelmed by Maki-san’s generosity, we walk by and through the Tsutaya Bookstore buildings recently completed by Klein-Daytham Architects, a rare partnership of imports from the UK that make Tokyo their home and practice a distinct architectural fusion. While built with a 21st century approach to design, the buildings respond to the scale of their surrounding context – both Maki’s Hillside Terrace and those that appear to be vernacular.

Our understanding of the Tsutaya Bookstore poses an interesting question about what vernacular means in Japan. Tokyo does not present itself as a city that places importance on tradition when it comes to architecture. It appears to be in a state of permanent flux. Buildings are being replaced by new buildings, and those are in turn being replaced by newer ones, and so on. While this is largely due to high land values and the relatively low value of buildings, a recent article published on Archdaily (“Why Japan is Crazy About Housing”) explains how in Japan no one buys old houses to live in them, and that the value of property declines as they get older, which is opposite to what we would expect in the Western world.

In Tokyo, new construction replaces and fits within the existing fabric, and design guidelines are nonexistent. We ask ourselves how one of the most design-oriented and savvy cultures, in our eyes, is so robust despite having no regulations or controls. George Kunihiro later confirms Maki’s words – vernacular is the attraction to craft, not the building. The Tsutaya Bookstore buildings are immaculately detailed and built; the precast concrete screen facade, composed of ‘T’ for Tsutaya, is a ubiquitous exercise in singularity with just the right balance of restraint and ornament. We are scheduled to have a conversation with Mark Daytham the next day – who casts a different light on our understanding of architecture as it figures in Japanese culture – but the Table for Twelve dinner is tonight.

DINNER

We arrive at frontofficetokyo after an afternoon spent soaking in Tokyo and a break for noodles at a quintessential udon shop. Bill Galloway and his Dutch-born business partner Koen Klinkers have rearranged their workspace to act as a setting for the evening’s discussion around a make-shift dinner table. The guests that join us are approximately half ‘imports’ and half locals, and the conversation is quick to start, inspired by Johanna’s short presentation and fueled by great wine.

The conversations confirm what Maki-san suggested – that the Japanese do not care about architecture, but craft. In one of his closing statements, Maki-san iterated that the position of their office in the architectural world allows them to demand quality, and while they might not have to do that in Japan, it assures that their buildings in North America follow this great tradition.

We ask our table guests and our hosts to comment and describe the construction process in Japan. It quickly becomes clear that the process in Japan is quite different than the one in North America. In Japan, contractors take on projects as if they are their own. The contractors are in charge of constructing the building, and most likely the ones that will know all of its intricacies. This is recognized through the fact that they assume full liability. Architects do not carry professional liability – contractors do. Our guests describe instances where contractors will often come up with details that achieve architectural goals but are technically superior, and perhaps easier to build. There are no proposed change notices or change orders. There is pride in building that is based on mutual appreciation of craft. The relationship between the architect and the contractor is one of respect and understanding of each other’s ambitions. This dynamic is unprecedented for North America, where the moment construction starts, finger pointing begins and everyone is concerned about protecting themselves, with the craft getting lost somewhere in the process.

After a few more days spent exploring Tokyo, SANAA’s architecture, and getting a hang of the train system, we are left to ponder the lessons we can extract and bring home with us to Canada. While it seems impossible to export the appreciation of craft to a North American context, strengthening and evolving the relationships with our builders certainly seems like one very good place to begin.

2 Comments

Many of the crafts are dying out over there - the prefectures often host artisan craft courses (one example I know of is carpentry, a 1~2 year program to learn wood from forestry to finish carpentry); perhaps encouraging craftsman in NA to enroll?

Nice article

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.