As it was Manhattan in New York nearly a century ago, China turns into a new stage in world architecture.

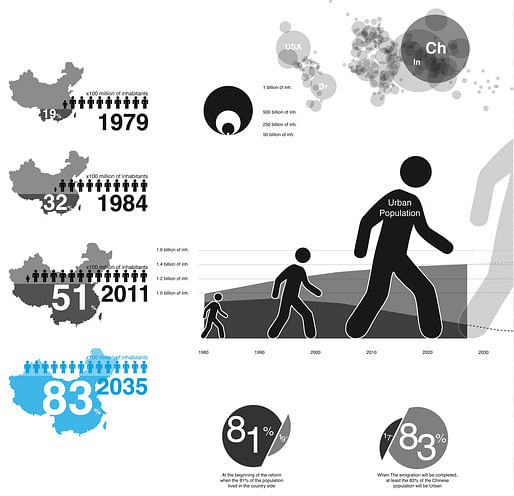

The facts and figures behind Asian urban growth compared to Europe are incredible: it is five times faster, what took 100 years to happen in Europe has taken place here in just 20; it is also 8 times bigger, 23 cities in China have populations of over 5 million whereas there are only 3 in the whole of Europe, and all this concerns an overall population that is twice as big, 731 million in Europe compared to 1,342 million in China. At the moment, the urban population is bigger than the rural population, accounting for 51% of the total. It is estimated that this will rise to 83% in 2035, when the process will eventually stabilize. The urban population requires services and infrastructures that call for a design approach based around big numbers.

The physical appearance of Chinese cities is strongly influenced by demolition: “Only 10% of historical buildings in China have survived to the present day” (Wang Shu).

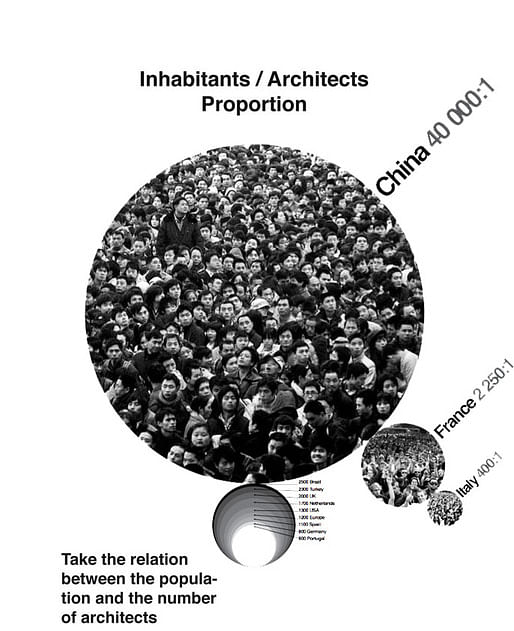

Knocking down historical cities means that Asian society must constantly come to terms with the idea of a “Blank Slate”. The number of architects in the country is extremely significant. The ratio of inhabitants to architects is 40,000-to-1, an incredible fact considering that in Italy there is an architect for every 400 people, a figure that is 100 times higher than in China.

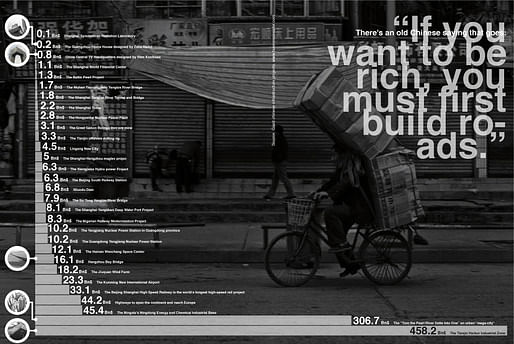

Chinese architects need to be much more efficient than their western colleagues in order to find work. China uses 33% of the world’s overall consumption of reinforced concrete. Chinese architects account for 1% of the world total, but the turnover from building work is 1/10 of the world total. In other words, one hundredth of the world’s architects must design of 33% of all buildings and they must do this for just 1/10 of the profit. This constitutes the theoretical state of Chinese architecture.

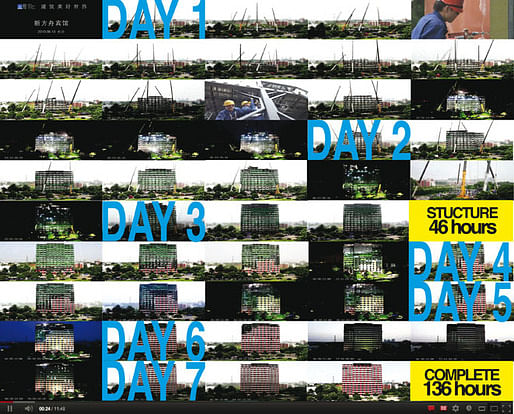

Nowadays the state in which Chinese architects work calls for a reduction in both building and design schedules. Design operations are becoming mechanical, just like industrial production, and there is no time to stop and think. The speed at which operations unfold and the desire to create distinctive locations have resulted in works like “One City Nine Towns” in Shanghai, European-style satellite cities.

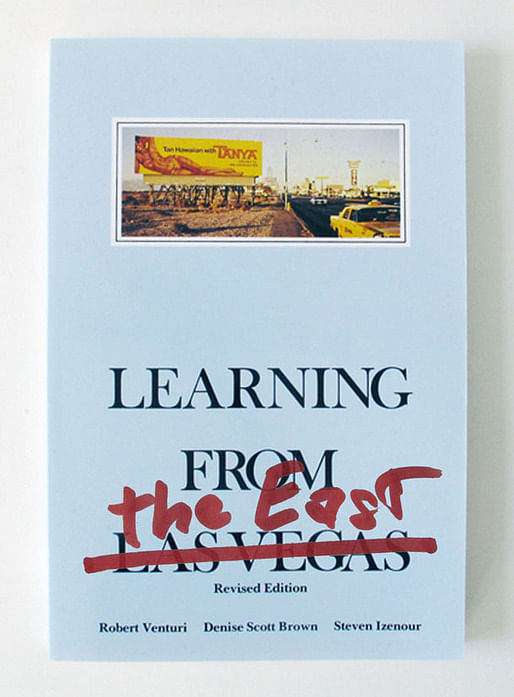

China would like to experiment with Western life and it matters little that this is just a copy of an outmoded and dated notion of Europe. The matter of importing Western styles and mixing them up to produce buildings creates a hybrid kind of architecture, lying somewhere on the cusp between these two different cultures.

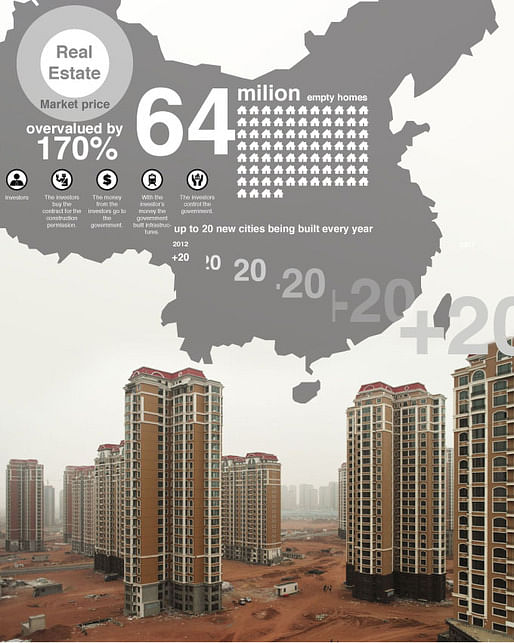

Architecture in China is a business. Real estate is constructed and exploited and when it has given everything it can, it is just knocked down to provide room for a new investment. “Tofu Buildings” are buildings in which materials and technology are sacrificed to lower production costs and speed up construction times.

Not even Archistars like Zaha Hadid have managed to avoid falling into this trap, and her Opera house in Guangzhou bears witness to the consequences of this kind of building philosophy.

China wants to be respected and attract attention, so the Government’s tendency is towards recognizable, imposing and iconic works of architecture that seek acknowledgement on the world stage.

The Archistars have entered the Chinese architectural scene backed and commissioned by the Government. This means China is becoming the latest world architecture stage, just as Manhattan was in New York almost a century ago. Cities are still the main showcases for the nation’s modernization and Deng Xiaoping wants Pudong to be Shanghai’s “Chinese Manhattan”.

“Nostalgics” still want “Chinese-ness” in architecture based on the idea of reconstructing entire sections of the city in traditional style. “Traditional Iconic” focus on boosting the scale of cultural tradition in term of image drawing on such conventional symbols as mountains, fans, dragons and coins to make their buildings iconic representations of “Chinese-ness”.

Nowadays the so-called “Returning Students” may be seen as the latest attempt to import new ideas and knowledge from the West.

This category is represented by architects who have studied at leading foreign universities and are open to experimentation contaminated by Western notions. They reject the current architectural situation, opting for a language based on the purism of tectonics, radical forms, vernacular materials and simplified building technology.

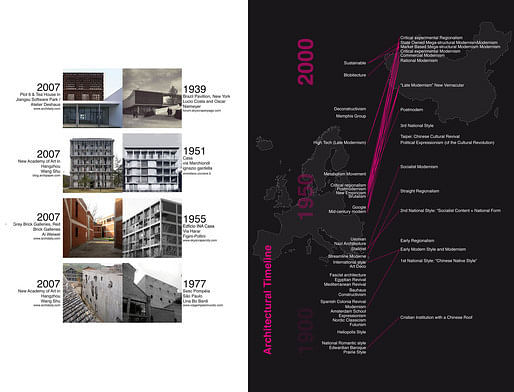

If we compare Western and Chinese architecture, we can see that there is a real time gap. Studying the current methods of architectural design used by the latest generation of architects, we can see that they have a lot in common with the post-war architectural period in Europe and the West: such as New Empiricism in Sweden, Neo-expressionism in Germany, Neorealism in Italy and Novo Brutalismo in Brazil.

Issues of “After the Modern Movement” discussed in Europe fifty years ago are now on the agenda in China.

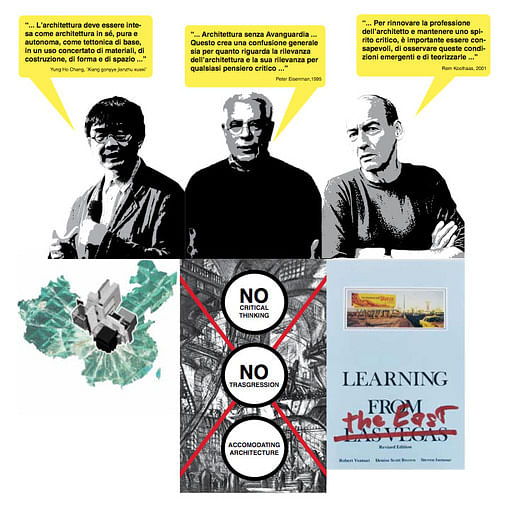

The writings of Yung Ho Chang, a Chinese architect and theoretician, clearly convey the message of the need for critical architecture that goes against the present-day consumerist situation based on the independence of architecture, radical forms and the use of vernacular architecture.

In an article entitled “Critical Architecture in a Geopolitical World”, Peter Eisenman raises the issue of the theoretical shortcomings of Chinese architecture caused by the influence of economic factors. Koolhaas talks about the need to pay attention to these emerging phenomena and to study them from a theoretical viewpoint as the necessary attitude for upgrading the architectural profession and maintaining a critical spirit. The cultural upheaval characterizing the latest generations has resulted in hybrid architecture in which marketing guides design.

The big numbers involved in Chinese architecture, the Olympics and Expo, not to mention the economic boom, have created the possibility and need for building. But China is still trying to understand what its own architecture should be like, ever since it finally opened up its doors to the West.

- Submitted to Archinect by Pier Alessio Rizzardi

Pier Alessio was born in 1985. He started his bachelor architecture studies at PoliMi (Milan, Italy) and attend an international exchange at FAU-USP (Sao Paulo, Brazil). He got the Master's Degree at PoliMi in the end of 2012. Now is working freelance at AM Progetti, based in Milan, meanwhile he collaborates with l'Arca International Magazine. Since 2007 he got experienced in several architecture studios: UMM-ONG (São Paulo, Brazil), Atelier Traldi (Milan, IT), Bamford Dash architecture (Melbourne, Australia) and MUDI-JDS (Shanghai, China), he collected numerous experiences worldwide, in the fields of the architectural design, urban development, social issues and identity in different realities; creating a leaning for international and multicultural environment.

11 Comments

When ever I see OMA style maps and presentations, I think of Colin Powell presenting Iraq WMD to the UN. Charts and clever pictures may impress, but lets face it, these developers are building postcard pictures that are shitty buildings, hells on earth to experience and live in.

Well, he is cynical.

This article is has a nasty, racist undertone. Or overtone, if you look at the pictures.

i'm also offended by some of these collages... though i can't articulate why. the first one with the woman and the one with the chinese artifacts.

I am super offended by this article - especially the collages of "Chinese-y" artifacts - tofu? And what is up with the scantily clad Asian woman? These collages do not demonstrate a point, but rather are images to shock and amuse - except they disgust and annoy. Archinect needs a better editorial board if this is what they are labeling as "News" worthy.

Developments that are happening in Asia require a thoroughly researched, nuanced study. Not this racist vitriol about how China can't match up to its Western counterparts.

tofu is food's tabula rasa - pretty clever

I also find it a bit racist that asians are only discussed by statistics. Admittedly the chinese government is not humanist by any standards, but it takes a different meaning when these studies are done by OMA type "intellectuals." The author mentions Wang Shu but does not share his values.

the imagination of archi-media is a strange thing. it can glorify a chain of occurences that it might well condemn in the future say for its impact on the enviroment and human living conditions.

Follow me on twitter: https://twitter.com/PARizzardi

Follow me on Blogspot: http://pieralessiorizzardi.blogspot.it/

Check it on linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/pub/pier-alessio-rizzardi/28/411/a43

Though the collages may demonstrate questionable taste, it's no secret that Chinese developers often turn to facile metaphors to sell architectural projects. It's a marketing strategy perfectly suited to the accelerated project schedules in China, where developers need easily-understandable narratives and flashy imagery to get their projects approved for construction by busy, distracted government officials.

Moreover, these collages seem to reference a recent cultural phenomenon: on the "chinese internet" (ie, Weibo, Renren, QQ, etc), architectural critique often takes the form of photoshopped renderings, plus commentary. CCTV becomes "the big underpants" - Shanghai's World Financial Center becomes "the bottle opener" etc. This type of visual commentary is healthy, embarrassing though it may be to foreign architects.

The "tofu" image in particular strikes me as smarter-than-it-seems. In China, the term for "Tofu" in an architectural context often refers to shoddily-constructed work and, often, associated government corruption. I would not be surprised if the author had pulled this from a weibo post.

If there's anything offensive about this essay, it's the suggestion that Chinese architecture has somehow to contend with the influence of "western" culture - as if this is a new phenomenon. While communist China may have only "opened" to "the west" in the last 30 years, the Chinese have been in contact with (and trading partners with) western European nations for hundreds of years, and for most of that time (until the industrial revolution) was the dominant and more technologically-advanced partner. While China faces a 'crisis of modernity' of sorts, it's reductive to compare this directly to postwar Europe. The context (both global and local) could hardly be more different, and the demographics are on a radically different scale.

I find the idea that there's no "theory" in China laughable. Of course there is architectural theory - but it's in Chinese and thus inaccessible to us armchair critics (of which I am one, for sure). There are a number of architectural journals in China, where critics and theorists discuss the state of architecture and the arts in a resurgent China, and debate the role of history and tradition in a modern state. This should come as no surprise.

Even if we can't read Chinese, we can see evidence of this debate in the built work of prominent Chinese architects. Wang Shu, obviously, seems to propose an alternative to the facile-metaphor-makers. In Amateur Architecture Studio's work, there is an attempt to find a balance between iconic image-first architecture (that clients and governments demand) and a regionalist approach to craft and scale. Liu Jiakun, for example, does similar work, tweaked to local (Sichuan) conditions. Urbanus (based in Beijing and Shenzhen) have a number of projects that eschew the iconic in favor of forms based on vernacular typologies - tweaked enough to be commercially viable. Even if none of these architects were explicit about the theoretical basis of their work, it would still be evident in the results.

Anyway. This could be an interesting debate.

謝謝, 先生 Chakroff!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.