Drawing details is one of the foundational skills of an architect and the levels of mastery are seemingly endless. How does one communicate complex assemblies in two-dimensions? This is the constant question of the architect. Early on, it may feel unclear how to tap into this higher level of thinking, to move on from merely picking up redlines, drawing floor plans, elevations, and sections. Taking initiative is essential to one's professional development, and it's the same with this. Here are 3 ways that a design professional can grow in understanding details:

It's one thing to be able to navigate a set of drawings, but it's an entirely different thing to truly understand its contents. When starting out, young professionals typically spend a lot of time interacting with already completed or semi-completed sets of drawings. It could be picking up red lines, modifying layouts, or organizing sheets, whatever it is, capitalize on the opportunity and pay close attention to what you're interacting with.

When picking up redlines, seek to understand why you are doing what you are doing. Why should the wood at the base of a cabinet be pressure treated? Why was the gauge of a unistrut changed? Why do you have to figure out a way to add an additional egress door to a room? Asking "why" will become an indispensable part of your growth. It's by understanding how things work that we are able to create them ourselves. The answer won't always be clear right off the bat, but sooner or later you will either have the opportunity to ask a mentor about it or you will discover the answer in a later project. Keep this up, and your detailing chops are sure to increase.

Whether you're accompanying a more seasoned architect on a construction site, reviewing drawings in the office with them, or even eavesdropping on their conversation with an engineer, observe closely and deeply. Similar to the previous point, the goal here is to observe and learn from how they do things. Good mentors will explain why they are doing certain things, but if you're not paying attention you'll miss it, and even then, it'll take hearing certain concepts over and over again to really get it.

The point here is to notice those things that aren't being said. Seek to get into the head of the person above you. Detailing is all about understanding how things go together and seamlessly knowing how to communicate that on a page. Seasoned architects have a special way of thinking about this, if you watch them, you will start to uncover that skill that's taken them years to cultivate. When you go back to your desk to work on a design problem ask yourself how the person you've been watching would approach it, you'll be surprised at the things you come up with.

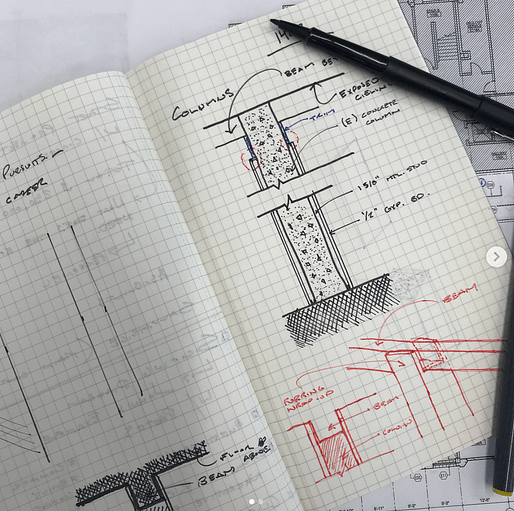

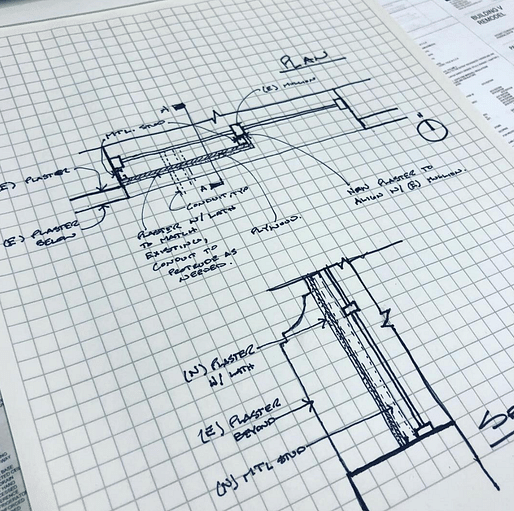

Sketching is an ancient way of working through complex ideas (I mean, look at Da Vinci's notebooks). When it comes to architecture, the benefits of putting one's pen to paper and physically working through the difficulty of figuring something out is invaluable. Maybe you're in the DD phase of a project and a project architect asks you to work on some ideas for a facade detail of a building that wasn't refined in SD, let's assume that this an important focal point of the project. One approach would be to focus on the more aesthetic aspects of this element (color, material, geometry, etc.).

But take that a step further and start thinking about how this thing is going to attach to the building. How does your choice of material and shape influence this? What implications do your ideas have on the structure of the building? Sketch these things out as you work through them (of course, this should fit into your workflow, all projects will be different). You can do the same thing in the field or in your free time. If there is an issue that needs figuring out on the site, get out your sketch book and try some options, at first it may not be great, but the more you observe, practice, and understand, the better it will get.

————

In the end, it's going to take time to get good at architecture, but with persistence and curiosity, gaining greater competency is inevitable. Remember to understand the work, observe the masters, and work through preliminary ideas on paper and with time you'll be closer to better understanding details as a design professional.

Site visits are vital to understanding detailing in regard to sequence of work, construction techniques, problematic conditions, contractor's experience and methodology, etc.

If you’re not getting out into the field with eyes wide open you are missing a critical aspect of your development.

All 4 Comments

Site visits are vital to understanding detailing in regard to sequence of work, construction techniques, problematic conditions, contractor's experience and methodology, etc.

If you’re not getting out into the field with eyes wide open you are missing a critical aspect of your development.

+50 to that comment. I was on site yesterday and I immediately know there was a massive fuck up as soon as I stepped in. Big life/safety boo boo by the gypsum board trade. My drawings and instructions are bullet proof and the client knows this. Countless heads were severed from their scummy contractor necks this morning.

Miles hit it precisely. Observing and understanding field conditions constitutes number 0 for this list, ahead of 1, 2, and 3.

(I love those stories, NS. They make me warm and happy. Tell us another one! And don't leave out the looks on their faces at the moment they realize they are proven wrong.)

NS, as a student I'm curious how a fuck-up by the gypsum board trade could be a 'big life/safety boo boo'? Does it have to do with fire ratings?

^yes. We're responsible for proper fire-protection details and sometimes the trades just do whatever either because they did not read the drawings or just thought they could get away with something simpler/cheaper.

I cannot recommend enough getting a copy of the 5th Edition of the Ramsey-Sleeper Architectural Graphic Standards (1956 with the Eero Saarinen foreword).

This was the last edition before they began to eliminate the beautiful hand drawings and swapped them for sleepy text and wordy tables out of concerns of liability. It is a phenomenal resource for understanding conventional details and the best principles of conventional construction, the assembly of flashing, joinery, window sills, and everything under the sun. Allows you to make non-conventional details that last and will actually perform. It goes far beyond the scope and sophistication of anything you'd find in Ching's Building Construction illustrated, as long as you remember that details are not necessarily still to code, the solution is not far away.

This month's Weekly Challenge on Merriam-Webster's dictionary app has "Fashionable Words" quiz. Zhuzhing.

This can't be over emphasized enough; existing drawings, while helpful, are not the be all, end all. As-built drawings are. Existing drawings are often incomplete, early construction phase, and bare little resemblance to what you are looking at in the field.

I'd like to hear more conversation regarding AGS, I find them to be essentially good for graphics, and less for technical information. I am much more interested in SMACNA for instance, and HMMA manuals, let's hear it!

SMACNA is a decent starting point, but if I'm working on a building that has those conditions verbatim I'm probably looking for a new job.

As-builts are great, but I have yet to find a client who wasn't too cheap to go without.

I have worked on architecture and contractors side, what I lerant is that contractors do not like architectural details. They prefer their trades and supplier provide them more realistic details. In-fact contractors prefer two lines vs something that does not make sense. Working on the contractor side, we had to provide revised details to the design team to let them know the correct approach. Its time architect really crosses the line and sees where there detail stand instead of their ego.

There's no question that architects can learn important lessons from (some in) the trades on detailing. But the architect is responsible for the bigger project-picture that this or that tradesman is most definitely not. A change that might make sense to an installer or framer or plumber or sheet metal guy in the field to a column enclosure, or soffit drop, or window opening, or duct run could alter dimensions and relationships down the line, causing real problems. Communicating about possible improvements ahead of time (versus field improv without notice) can help.

historic coffered ceiling with fancy tin crown, the works... needed to slip some LVL headers in here and there. Crown was detached from below as described, left to hang, and the work was complete. It was difficult and annoying, I get it, but I came out for the weekly site visit to see some beautiful work and the crown pinned back. Came back the week following and all the crown is removed and crumpled on the floor while the sheetrock guys go... "well we couldn't put the sheetrock up without removing the crown"... uh, look at the damn detail, you're not rocking up to the ceiling. We stop shy, add a picture mould, and then the plaster guys were going to restore the remaining 6". I'm trying to hold them to replacing the crown at their expense, the framer agrees with me, he's pissed he did all that work just to see the crown removed. Half of it isn't salvageable. The owner is deer in headlights.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.