The apprentice model has been a fruitful approach for thousands of years, with a clear track of mentorship and milestones, young professionals were able to methodically progress in their careers. However, we must acknowledge that everything we need to know will not be freely given to us. In architecture, there are aspects along our path that we will need to uncover on our own. Adopting a practice of observation can provide us with a unique advantage in our journey.

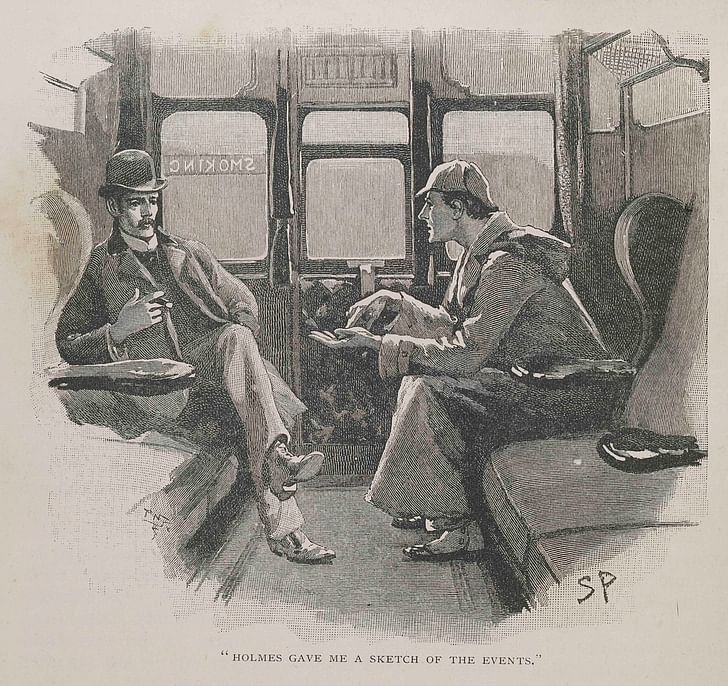

In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, A Case of Identity, we find Sherlock Holmes and his companion, Dr. Watson, discussing the detective’s observations of a prospective client. We can read of the encounter from the perspective of Dr. Watson:

“You appeared to read a good deal upon her which was quite invisible to me,” I [Watson] remarked. “Not invisible but unnoticed, Watson [Holmes in reply]. You did not know where to look, and so you missed all that was important. I can never bring you to realize the importance of sleeves, the suggestiveness of thumbnails, or the great issues that may hang from a boot-lace.”

Holmes goes on to explain to Watson how he was able to see that the woman had left her home in a hurry by the nature of her boots and that she had just written a letter due to her gloves and a small amount of ink that he observed on her sleeve. These turn out to all be details that help him solve the case.

What Holmes is able to do brilliantly is take a situation that seems lifeless and extract a whirlwind of information and insight from it. And while this feat is entirely fictional, as architecture professionals, we can learn something from him. We have to often take it upon ourselves to learn from observation as well. For example, in listening to how those more experienced than us talk to contractors, plan checkers, or clients, and taking note of what works and what doesn’t. Or noticing the more subtle qualities of a good project manager and how we can incorporate those aspects into our own work. Even, picking up on the nuances of what makes a great drawing or detail. By taking a lesson in observation from the mythical master (Holmes) we can position ourselves in a unique and powerful way, learning that which no one can ever tell us, but only that we can uncover from our honed powers of perception.

Most of us have a mentor or someone in our office that we look up to. Someone who has accomplished what we aspire to in our own lives. These are great individuals to start paying attention to. What is their routine when they come into the office each day? Maybe they check emails first, ask them why. Is there a particular way they approach a problem? Try and take note of that. I remember when I was first getting started in architecture if I would hear my project manager word something a certain way I’d ask why. There was one instance at a plan check review. I noticed that my mentor explained something to the plan checker in a way that was very different from how we talked about it in the office and so I asked him why. From that simple observation and question, I was able to learn that getting plans approved was not solely based on having good drawings. There was a social component to it as well.

... there will come a time when you will be given responsibility, and the depth of your observations leading up until then will have an impact on how you rise to the occasion

Martial arts has always been a part of my life, and one of the primary ways one learns in training is through close and deep observation of the instructor. How are they breathing? How do they move their hips? What muscles are being engaged? What is their state of mind? How’s their posture? The list is endless. It was the legendary Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Master Royce Gracie that said, “You win the fight in the training camp, not on the day of the fight.” It’s the same with architecture, there will come a time when you will be given responsibility, and the depth of your observations leading up until then will have an impact on how you rise to the occasion. When I was finally sent to get plans approved by myself, I remembered what my mentor taught me, and I understood the social component of that meeting. As a result, it ended well, and I walked away with an even deeper understanding of how to operate in this setting.

As you move forward in your career, your interactions with other people will be one of the primary deciders of your success. Earlier on you can learn a lot by observing how people outside of your office respond to the personnel within. For example, let’s say you accompany your design principal to a client meeting. You’re mainly there to take notes (for the sake of this example at least). And the client objects to some of the design proposes. Your design principal tries to defend the thinking behind the options but the client doesn’t seem convinced, they even seem a little irritated. Your mentor takes some further steps to present the work, perhaps tying it to the client’s initially expressed goals. At the end of the meeting, things seem well, and the client has bought into the design.

What did your principal say or do to reconcile the client’s initial disapproval? Was it her tone of voice? Her body language? Was it merely that she acknowledged the client’s concerns? It’s your job, as an observer, to try and snuff out those details. It may take five meetings to start to notice patterns, but it is a great way to begin to learn how to interact with clients.

Earlier on in my career, I took this approach with Consultant Coordination and Construction Administration. I was always so afraid of the thought of having to talk to an engineer or contractor because I thought that they would think that I was incompetent in some way. As I shadowed more experienced architects in these settings, I was able to slowly uncover the simple fact that I was overthinking the whole thing. I would hear architects with over 35 years of experience ask the sub-contractors their thoughts on how to solve a problem on site or to clarify on something they spoke about. Paying attention to these interactions helped me to see that my assumption that I needed to know everything was drastically misplaced. It was okay to say when I didn’t understand something. I learned to realize that the engineers and contractors I was so intimidated by were just people like me and most of them were happy to help me along the way as I grew to obtain these responsibilities on my own.

We also want to pay attention to how we are perceived by those around us. To do this, we have to uncover our natural empathic abilities. When you talk, how do your team members receive what you are saying? You can learn this from how they respond to you and their body language. Are you always butting heads with someone? What can you do to soften those interactions? Maybe you unknowingly come off too strong to some people. It could even be possible that you appear not to take your job seriously even if that’s not the case.

Throughout my career, I have always sought out periodic feedback from my mentors. On one occasion I was told that it always seemed like I was trying to find a way to get out of doing the work that was assigned to me. This was a shock to me because I thought of myself as a diligent and devoted worker, but I would always try to propose more efficient ways to do tasks or question the necessity of certain things. When I received that feedback from my mentor and took a moment to see things from her perspective, I was able to see how my good intention actually came off dodgy.

Take a step to pay attention to how you influence those around you and try asking for feedback from those above you

From that meeting, I was able to reframe how I presented those suggestions to the team which allowed for more fruitful interactions down the road. The less self-absorbed we are with our personal feelings and good intentions the more we will have the openness and willingness to adapt and grow in our career. Take a step to pay attention to how you influence those around you and try asking for feedback from those above you. In the end, be open to whatever you uncover.

It was Leonardo da Vinci who said, “the artist sees what others only catch a glimpse of.” He learned almost everything he knew from observation and practice. It was not until later in his life that da Vinci embraced the power of learning from books. He was a proponent of learning by experiment. Every phenomenon he studied began as obsessively close observations followed by hypothesis, experiment, and finally, practical knowledge. In Walter Isaacson’s biography on the famous polymath he opens and closes the book with an obscure task from one of Leonardo’s famous checklists, it simply read: “describe the tongue of a woodpecker.” Even Isaacson was perplexed as to why anyone would want to know what the tongue of a woodpecker would look like but as one studies the life of the ancient master we see that he had to know. It was an inherent part of his nature.

At every stage in our careers, we too must adopt this same curiosity and devotion. At every level, there will be opportunities to learn something new. The more we strive to see the subtle things that everyone else misses, the more we will be able to capitalize on those insights. It is in the nuances that one can begin to stand out.

I remember after about a year of working professionally I noticed that one of the principals at the firm I was working at the time always showed a subtle sense of relief and appreciation when a project team would have a well-organized presentation for him (for an impromptu design review of some kind). He never commented on it, but when he came to meetings where things weren’t as organized it clearly frustrated him.

After a couple of months of seeing this, I noticed that it was a particular job captain who would have his team take extra time to prepare their presentations. Even though they weren’t formal reviews, this job captain treated them like they were. So the next time I had a review with my project manager I took some extra time to prepare and pin up my work nicely. And after that meeting, I started to do it with every session. And every now and then people would comment on how clear and easy to follow the ideas were.

Whether it is a sophisticated design idea or a simple one-page document. Everything should be done with the highest level of care

Ultimately, I adopted an idea that I always share with those that I mentor or train now. Essentially, it is to have overwhelming respect for the time of every person within a team. Not just the principals, but every member of the staff. One should imagine they are preparing a presentation for Rem Koolhaas, Frank Gehry, Le Corbusier, or whoever they deeply admire. Whether it is a sophisticated design idea or a simple one-page document. Everything should be done with the highest level of care. This simple idea has brought me tremendous favor in my career, and I owe it to that job captain. Not because of anything he instructed me in, but solely because of his example and my willingness to observe and learn from him.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

1 Featured Comment

Good advice for any career, Sean. I wish I read this 40 years ago.

All 3 Comments

Good advice for any career, Sean. I wish I read this 40 years ago.

Gary, I really appreciate the comment!

Reminds me of something one of my favorite architects, Henry Hobson Richardson said......"It doesn't matter who comes up with a great idea, what matters is the ability to recognize an idea as great." I've always taken this to mean, listen carefully to others, be they the client, your co-workers, or yo mama. Great ideas come from the least expected places. It frees one of the tyranny of originality.

Totally agree!

Agree with your observations. Holmes was a very good instructor and graciously shared his knowledge. Watson was a very good student. They were an “ideal pairing”. If you are going to be a teacher, trainer, and mentor, this duo is a good example to follow. You may not get a student like Watson, but you should commit to being a teacher like Holmes just the same.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.