Today we finish off our series of conversations, or "Mini-Sessions", with architects and designers in LA and Detroit, sharing our conversation with Lorcan O'Herlihy. Lorcan is an Irish-American architect, with offices in Los Angeles and Detroit. His recently published book, Amplified Urbanism, was recently reviewed on Archinect.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Dublin Ireland and I came here at a very young age to Los Angeles. I was two years old. My family was in the film business. My dad was a film actor so my early years was traveling extensively between the United States and Europe. I went back to Ireland at the age of eight and went to school there through 15, my formative years were spent in Dublin. I came back here at the age of 15 and began studying architecture in university when I was 16.

Sixteen is so young to be starting architecture!

I was 16 years old as a freshman at University. I was extremely green.

Where was that?

I have an MA in History and Theory from the Architectural Association, presently called the MA in History and Critical Thinking. My BArch degree is from California State University San Luis Obispo.

Do you remember what was your earliest motivation to study architecture?

I come from a creative family and I have great respect and admiration for my brothers and sisters and my dad. My father and brother were film actors. My sister was an artist and was the managing director of the Great Lakes Shakespearean Festival, and also was involved with the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. It’s been a very interesting life being involved the arts, and I was inspired to be in a creative field. In addition to being a film actor, my dad had a degree in architecture as well. He had a BArch from the University College Dublin and was a colleague of Kevin Roche, his friend from college.

How did your career start after school?

My first job was an internship at Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates, in the early 80s. I spent my first few years there, in Hamden Connecticut. Around 1983 the Louvre Museum came on my radar. Needless to say, I.M. Pei was selected for that project, and I interviewed at IM's office, landed a position, and worked on the Louvre for three years.

I had a wonderful time working both in New York and in Paris on the project. After that period I became an artist in New York. A few years later I decided to return to architecture, and the only architect I wanted to work for was Steven Holl. I was fortunate to land the job. After a number of years at Steven’s, I decided to start to start my own practice in Los Angeles.

In your opinion, what is the role of an architect?

I believe that architecture is a social act and that the role of the architect is to do work of consequence.

The goal of our field is not so much about how to design a building as an isolated object, but how to use architecture as a tool for engaging in development, politics, and social structures, in order to amplify our urban landscapes and elevate the human condition. Those are the principles that drive our work.

Since 1994, my firm, LOHA, has been engaging the dense side streets and bustling boulevards of Los Angeles (and now Detroit) with an array of projects that blur the lines between the public and private realm.

You just recently published a book entitled "Amplified Urbanism". Can you talk a little about that?

In January of this year, we unveiled a book called Amplified Urbanism that addresses the broad issues facing urban spaces. We invited a number of authors to present and analyze interdisciplinary ideas from cultural, civic, and ecological leaders with varying insights about city life. The goal of this publication is to provoke conversations about how cities may become more dynamic, sustainable and productive environments for all. The book highlights how the tenets of Amplified Urbanism have been successfully implemented by our firm, and how they may be used by others in all to cultivate vibrant communities.

Is there a recent project that you can talk a little bit about, incorporating the "third space" concept?

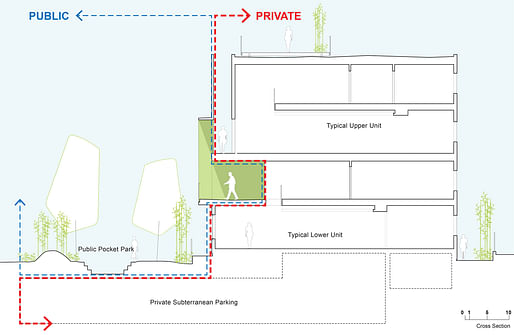

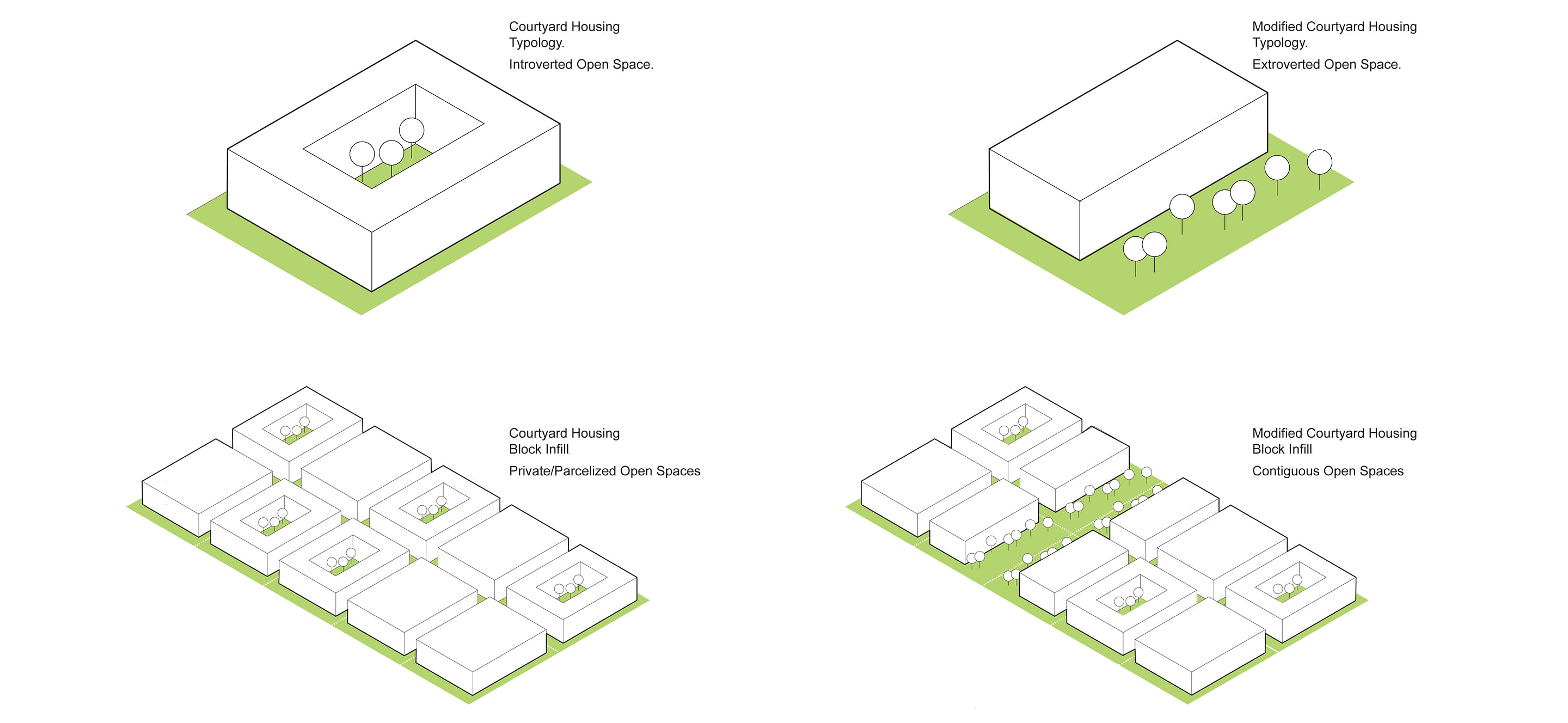

Formosa1140 is a housing project that we did in West Hollywood. We were able to work with the city to provide a public pocket park on private land. We managed to tuck the parking underneath this park but also made it for the city as opposed to a conventional type of courtyard housing which creates private common open space residents of the building.

Formosa1140 rethinks the convention of the typical courtyard housing typology, and we argue the case that you can provide a modified courtyard typology which pushes the massing to one side of the building, providing open space for residents and the public. The pocket park at Formosa is open to the public from dawn to dusk.

How did the residents respond to this approach? Is there a desire to take that space back as private space?

My client was Richard Loring who had a company called Habitat Group Los Angeles. Richard and I approached the city to pitch the idea. The challenges were that if this is a public park on private land who's responsible? Who's accountable? In effect, the owners of Formosa1140 own the land, but it's run by the city.

This approach was also applied to our Habitat825 project next to the Schindler House. There are benches in front of that building that we opened up as an extended bandwidth of the sidewalk, over 45 feet into the property, providing seating for the public.

It's a principle that I've been pushing on a number of projects over the years, and I continue to do that with all of our work.

For young architects out there that are that want to pursue this type of approach, what advice would you give to get started with negotiating this private-public space?

As I mentioned before, I believe that architecture is a social act. You need to take an approach to architecture that pulls away from seeing a building as an isolated object, but instead see it as an tool that engages social and civic interactions. You bring all of these variables to your project. When presenting to a client the idea of providing part of your property to the public realm, it is important to argue that it is a win-win situation for not only the architect, but also the client and the city at large.

A big part of your work seems to be dedicated to making cities more livable. Interestingly, you work in Los Angeles and Detroit which are two cities that seem to be, relatively, challenged in terms of livability. Are you applying the same type of approach in Detroit? Does Detroit demand different types of solutions than Los Angeles does?

It's a fascinating period. We're working on five projects in Detroit right now and I've always been intrigued about the parallels and the contrast between Los Angeles and Detroit. In Los Angeles, we’re confronted with how to strategically design projects on dense infill lots. In Detroit, we’re faced with the inverted figure-ground relationship of a dramatically underdeveloped neighborhood fabric.

When you're designing projects in Detroit you have to recognize the future. The ambition and visions that you want within Detroit has to be specific to the culture and ecology of the city. What that means is that it has to be for the people who are there.

There's been a significant change how Detroit is growing right now and it's about developing neighborhoods. That's a very unusual shift from the past. The previous approach has been to develop downtown Detroit and then let that trickle down to the neighborhoods. You can't bring the approach one takes in LA and just apply it to Detroit. In Detroit, it's about how to create urban renewal in the neighborhoods. Not only build for new people to come, but also to recognize the importance of designing project for the people who are already there.

Thanks Lorcan!

If you’re able to attend the LA Design Festival, make sure to check out the live panel, titled LAX >< DET, discussing the connection between LA and Detroit, a collaboration with the Detroit Design Festival and the L.A. Forum for Architecture and Design. The event will be taking place on June 10th, from 2-4pm at ROW DTLA 777 Alameda Street, and will include Edwin Chan, Chris Denson, Lorcan O’Herlihy, and Eileen Lee.

3 Comments

None of the people in this series have any meaningful connection to Detroit (with maybe the exception of Zago).

This series features discussions with architects and designers that live/work in both LA and Detroit. Our objective is not to discuss Detroit in detail.

As someone who both lives and works in Detroit, I stand by my original comment.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.