According to Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects’ new monograph Amplified Urbanism, not only has Los Angeles arrived as a city with its own idiosyncratic urbanism, but that urbanism deserves bolder, louder expression through architecture.

The Los Angeles offices of LOHA have a David Lynch quality, especially when I visited them on an evening blanketed by moonlit clouds. Neon signage glowed on a former industrial warehouse, barely illuminating a smiling security guard who asked no questions and offered no answers. It looked less like an architecture firm and more like a hip club; but once the windowless steel door clicked shut behind me, the Lynchian vibe gave way to a design studio in sumptuous launch party mode. The book attempts to not only redefine what urbanism means, but makes a case for “amplifying” itModel display tables had been cleared to make way for charcuterie and cocktails; a catering truck, located on the edge of the palm-tree ringed patio in back, funneled wedges of tooth-picked pork and crunchy-bedded hamachi via waitstaff who took compliments very seriously. This launch party was, as I was about to discover, a vibrant microcosm of the concept of Amplified Urbanism, LOHA’s research-book/monograph that we had gathered to celebrate.

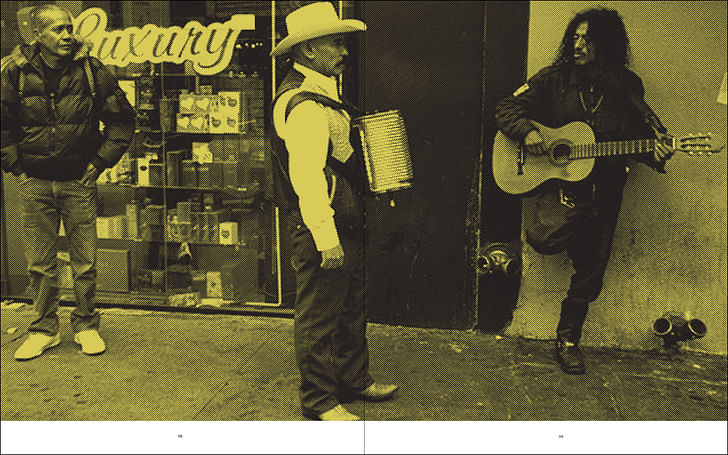

In addition to featuring texts by recognized architectural critics such as Linda C. Samuels and Greg Goldin, Amplified Urbanism purposefully incorporates authors who are not exclusively associated with the field, including Wendy C. Ortiz and David L. Ulin. The monograph is therefore as multi-dimensional as the city it primarily investigates (Detroit’s legacy “of industrial innovation and creative entrepreneurism” is also briefly explored). Although an essay by Christopher James Alexander is dedicated to explaining how each of LOHA’s projects interacts with the inherently complex urban fabric of Los Angeles, the monograph as a whole takes pains to illuminate the city’s soul and vibe. The book attempts to not only redefine what urbanism means, but makes a case for “amplifying” it. If Los Angeles could be likened to a cult vinyl release, its tracks often sampled but rarely played in their entirety, then Amplified Urbanism is the listening party, encouraging us all to crank the city up.

LOHA’s work functions as tangible examples of this amplification. Christopher James Alexander analyzes how principal O’Herlihy used Main Street in Santa Monica “as an incubator for his evolving design strategies,” specifically with regard to the Julie Rico Gallery, which with its carved out rectilinear volumes “allowed the streetscape to infiltrate the building envelope and lured the gazes of passing pedestrians into the art-adorned interior.” He also studies how LOHA (re)incorporates L.A. history, taking a look at the contextually-sensitive 1997 restoration of Richard Neutra’s Beckstrand/Goldhammer Residence, as well as a new apartment building adjacent LOHA’s work functions as tangible examples of this amplificationto the Schindler House in West Hollywood. Meanwhile, the former car dealership turned into a mixed-use residential structure known as the Granville project “highlights how LOHA’s blend of intuitive artistry and precise architectural analysis results in powerful forms that boldly enhance the public realm.” Alexander also puts the city-as-random-sprawl-theory to bed. “One of the greatest myths about Los Angeles is that this metropolis developed without a plan. In reality, the city was deliberately shaped into a global powerhouse by specific urban-design strategies promoted by an array of vested interests. Some visions required longer incubation periods than others.”

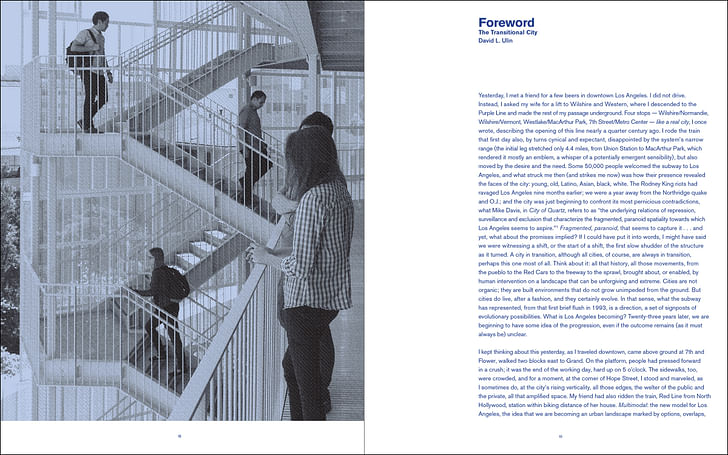

Each of the essays and pieces within serve as connective tissue between the bones of the architecture and the spirit of the concept. David L. Ulin, whose two essays gracefully unspool with his customary pairing of historic fact and nuanced feeling, examines the transitional nature of Los Angeles, and then paradoxically tries to define that transition. How do you describe the form of change, except in flashes? It’s an unending task, and his absorbing meditations always make it an enjoyable one. “What does it mean that we in Los Angeles are now having this conversation, that we are talking about places where people gather, that we are looking for the seams between public and private life?” he asks, as he interviews denizens like CicLaVia co-founder Aaron Paley and Clockshop’s Julia Metzger about the nature of Los Angeles. Ulin observes that “the belief that art not only reflects but also creates community, is, perhaps, especially relevant to Los Angeles.” Meanwhile, Judith Lewis Mernit chronicles the city's fraught developmental history with water, tracing how LOHA conceives of revamping the city's major waterways to minimize impact to existing facilities like ports while simultaneously embracing a more "natural" approach.

Wendy C. Ortiz, who in her books usually charts emotionally searing territory with unflinching cool, has written the most abstract and poetic sections of the monograph, each of which accompanies an image of one of LOHA’s projects. “I went to the library and began reading architectural monographs,” she told me at the party as we moved through a cavalcade of robust-looking structural engineers, designers, public radio hosts and art world professionals. “I wanted to try and find some kind of common lexicon.” Los Angeles has struggled for decades in the shadow of expectations of what a “great city” should beShe said she was absorbed by the rhythms of the language she uncovered, and subsequently began writing pieces that were based on the imagery she was given of LOHA’s work. The result is a very interior, intimate rendering of the blurring between private and public space; she creates portraits of encounters between materials and people, so that the buildings almost seem to be as emotionally aware as their human narrators. “An urban landscape experiences a shift in its inhabitants’ internal landscapes," she writes. "Waves of change over decades transport us to the moment, this overlap that connects history to the present.”

The afterword by Greg Goldin summarizes Amplified Urbanism and the reality of Los Angeles itself: “Here, no ancient civilization casts a decisive shadow, as the Acropolis does in Athens, or Tenochtitlan, with its terrible gods and fortress walls, does from the center of Mexico City.” And yet, Los Angeles has struggled for decades in the shadow of popular expectations of what a “great city” should be, puzzling and alternately disappointing traditional urban critics who could find no ready-made category for its multivalent culture. Luckily, LOHA’s monograph makes the case that it is time to start celebrating L.A.’s offbeat urbanism. As I left the launch party, I looked up to see the moon, so long obscured by cloud, finally breaking into uninterrupted beam.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.