Beneath the vertiginous LED-strip lighting of Michael Maltzan's Billy Wilder Theater, a diverse audience gathered last Tuesday for a talk entitled "The Next Wave: Urban Adaptations for Rising Sea Levels." Co-presented by the Hammer Museum and UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, the event brought together coastal geomorphologist Jeremy Lowe and civil engineer Peter Wijsman in a conversation moderated by Kristina Hill, a UC Berkeley Professor of Landscape Architecture. The talk was part of an on-going lecture series on "the most pressing issues surrounding the current and future state of water."

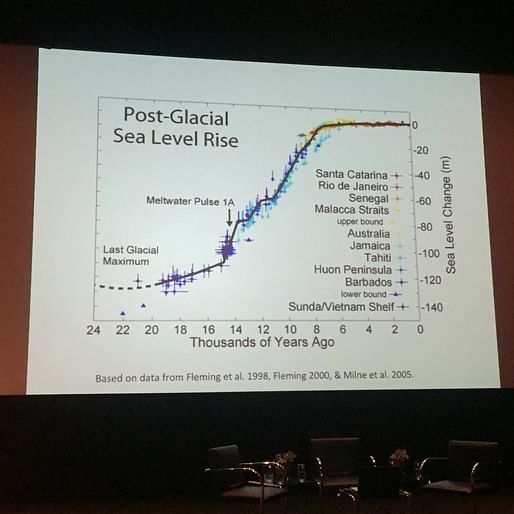

Hill began the evening's panel with a brief introduction to the unfolding realities of sea level rise, as well as some of the efforts underway to mitigate its impact. Pointing to an image of the San Francisco's Embarcadero embattled by high tides, Hill discussed the urgency of our particular temporal moment: we are in the last slow period of sea level rise that the Earth will see for for over three centuries. At the same time, as she discussed the different effects that rising waters will have on different shore typologies, from sandy coasts to urban hard-edges, Hill stressed the importance of not thinking that there's a one size fits all solution because "there really isn't."

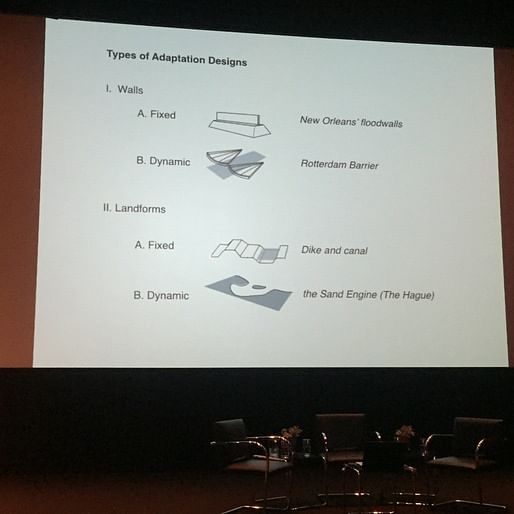

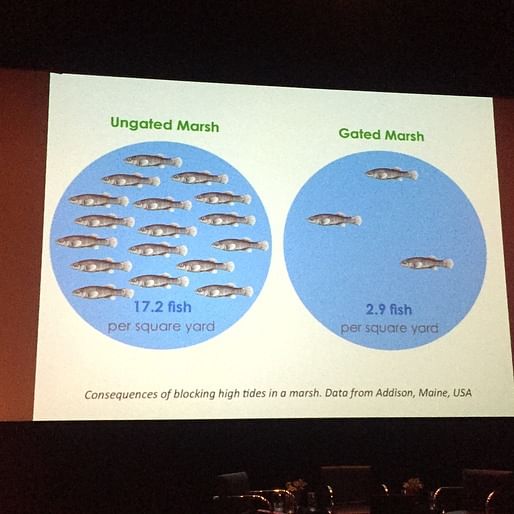

For the most part, Hill's case studies were international. After all, "we haven't done much yet in the US." Meanwhile, in places like the Netherlands that have experienced drastic flooding before (ie. the 1953 North Sea flood), diverse efforts are already underway. In the case of the Northern European country with nearly 20% of its territory below sea-level, many of the most interesting engineering solutions are not mere walls. Rather, as in the case of Hafencity, coping with sea-level rise also means "a question of cultural change and experiences of the world," of learning to be okay with getting your feet wet occasionally. Other efforts, such as dumping a large amount of sand off the coast and letting the tides distribute it, constitute "dynamic strategies that are actually cheap because they imitate nature."

As Hill's lecture opened into a panel, followed by audience discussion, the question of economic viability hovered over the room. Because of the historic importance of riparian and coastal access for trade, most major economic centers are along the water and therefore at risk. And as Lowe stressed, because of "the interconnections of the global economy," the issue is never merely local. The panelists stressed that resilience to rising water may be the determining factor in a region's capacity to maintain competitiveness in the market. While "development trumps the impact of natural disasters," as Wijsman noted, the group seemed adamant to articulate that adaptive development will have long-term financial benefits.

When asked by Hill what he believed to be the most significant aspect of sea-level rise overlooked in typical conversations, Lowe stated hope: "I see it as a great opportunity" for a "more unified coastal management," which is to say, for coastal design with "more than one objective." He argued that there should be "less doom and gloom" and even joked later that, "Hurricane Sandy was wonderful,” at least because it provoked conversation and has led to new developments. For Wijsman, the missing component was discussions on the benefits of tech, such as warning systems. And, in a logic similar to that espoused by Lowe, the tech companies themselves will benefit from adapting.

When asked by Hill what he believed to be the most significant aspect of sea-level rise overlooked in typical conversations, Lowe stated hope: "I see it as a great opportunity" for a "more unified coastal management," which is to say, for coastal design with "more than one objective." He argued that there should be "less doom and gloom" and even joked later that, "Hurricane Sandy was wonderful,” at least because it provoked conversation and has led to new developments. For Wijsman, the missing component was discussions on the benefits of tech, such as warning systems. And, in a logic similar to that espoused by Lowe, the tech companies themselves will benefit from adapting.

Other assertions of the economic benefits of adapting to sea-level change dominated much of the night's discussions. For example, the panelists continued to assert that leading industries in the private sector are already aware of, and working towards, adaptation. "We should therefore follow suit," seemed to be the suggestion. Generally, the talk was infused with a sort-of economic pragmatism that they channeled into a cheerful positivity.

I left the panel troubled by this, although I found it difficult to pinpoint exactly why. After all, the dire urgency of the situation was well-conveyed and their unusually hopeful attitude was a much-need antidote to the depression that such conversations usually provoke. At the same time, a certain schizophrenia pervaded their calls to think both globally and simultaneously within market paradigms that demands national, regional, and individual self-interest under the framework of competition. Climate change and sea-level rise, it is well-known, disproportionately affect the world's most marginalized populations who, incidentally, are often least responsible for increasing the levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. For Micronesian countries actively disappearing beneath the sea, adaptation is not a matter of maintaining economic competitiveness but of mere survival. In Accra, Ghana, the loss of wetlands is not just a problem because the water levels are rising but also because they have become filled with electronic waste illegally dumped by Western countries, which release toxins that inhibit the development of children's reproductive systems, nervous systems, and brain functioning. These are, no doubt, some of the same technological products heralded by Wijsman as one of the most overlooked components necessary to the conversation regarding sea-level rise. And it is hard to imagine, looking back at historical precedent, that corporate interests will always align with humanitarian or ecological imperatives.

As the panelists last Tuesday noted, the issues we face today are global and interconnected. The oceans are rising but so are temperatures. And the oceans are also acidifying; toxic e-waste is accumulating; entire species are going extinct; nuclear waste continues to be stored unsafely; storms are getting worse; more and more regions are experiencing drought or famine; the world's forests are being hewn; human populations increase; development continues unfettered. After the panel, I kept wondering: What does it mean to act or think pragmatically at this historical moment? That is to say, can we develop rationales for acting that take into account the whole of the world – not just the wealthy but also the marginalized, not only the human but also the inhuman? Such questions, it seems, may well define the contours of our collective future.

3 Comments

The impending global war will take care of a few issues, overpopulation and unfettered development, but will probably create a few more... I tend to wonder what the breaking point is going to be in regards to climate change and rising sea levels. If not now, when? How high is the threshold when so many have already been cleared that it's obvious that a lot is at stake? Like some of the speakers, I look at climate change as an opportunity to make a difference, and change the marketplace, but the "need" isn't there right now and all the awareness drives in the world won't change that. It's happening, it's going to happen, who will win and who will lose will be the questions the majority of people will ask, not how we can work together globally to make us all winners, it's not how we think as a species, and it's why we will all eventually lose...

it's interesting that the conversation is moving from 'how to prevent disaster' to 'how to live with disaster.'

if you are into this topic a good recently published book about the Dutch dike system, both the technical and cultural aspects: http://www.amazon.com/Dutch-Dikes-Tracy-Metz/dp/9462081514/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1426021389&sr=1-1&keywords=dutch+dikes

more info on the book's website: http://dutchdikes.net/

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.