In architecture, city-wide design concepts have a checkered history: public housing projects and century-old zoning ordinances seem to have created almost as many problems as they were intended to solve. And yet, the dream of the collective urban form may be restored with the work of the Harvard Graduate Design School’s new Office for Urbanization. Headed by landscape architecture professor Charles Waldheim, the Office for Urbanization is currently tackling the problems of sea level rise in Miami Beach, but the scope of its research is unearthing a promising new realm of possibilities.

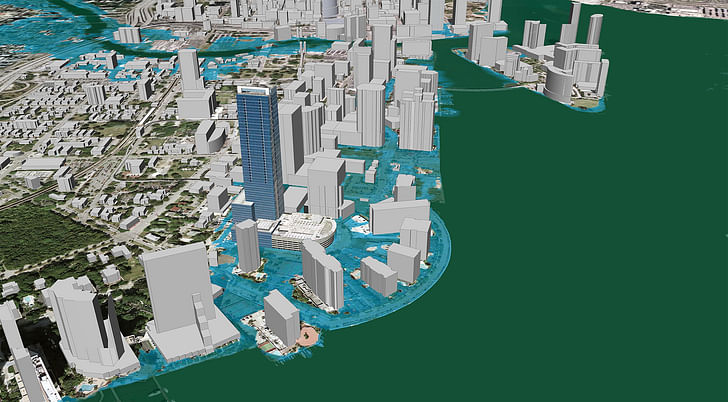

Thanks to the melting of massive ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland, the journal Nature predicts that by 2100 the world’s sea level will rise by six feet. While climate change may be frustratingly ambiguous as a political concept, as a practical reality it is already here. Luckily, the GSD’s Office for Urbanization is developing design strategies to deal with the impending tide, focusing its inaugural efforts on the city of Miami Beach. Of course, the work isn’t simply about elevating everything on stilts, but rather creating a holistic design program and strategy that could be applied to any city or region at risk. This involves understanding how to marshall the enthusiasm of numerous stakeholders and designers so that effective solutions can be enacted quickly across thousands, if not millions, of structures.

The scope of the program therefore is vast, both logistically and conceptually. The Office has not only partnered with areas directly affected by sea level rise, such as the Exumas in the Bahamas, but with firms like AECOM, over its work the Office has begun to explore ideas of collective form studying the urban development of new cities in China. Subsequently, the Office has begun to explore ideas of collective form, specifically by analyzing how the borough of Manhattan collectively interacts with sunlight. How does the design of one skyscraper, which may be modeled to allow sunlight to filter down to a street in Chelsea, relate to the solar-paneled exterior of a building on Roosevelt Island? Could there be a kind of shared currency of solar power, much like carbon credits, wherein large-scale design projects can be conducted in tandem to produce a city that thrives on solar energy, as opposed to a collection of disparate developments?

This examination of heliomorphism illustrates the concept of a collective urban form, which is contained within the broader scope of the investigations of the Office. I spoke with Charles Waldheim about the origin, inspiration, and direction of the new program.

How many faculty and students comprise the Office for Urbanization?

Since November 2015 we’ve had basically kind of a year zero, a kind of soft rollout where we’ve been building our own capacity, building staff. We have our inaugural conference coming up on Sept. 15 and 16th at the GSD. With that we’ll be launching our website and kind of rolling out more publicly. Over the course of the run-up to the conference, there have been dozens of faculty and research staff that we’ve been engaging with on a variety of projects.

You’re partnering with AECOM, and the Exumas, a series of islands in the Bahamas. What have you discovered so far, and how are you formulating a framework to pursue the office’s investigation?

The idea for the Office is something that we cultivated based on the idea that we had been doing these applied design research projects, the two that you mention most notably, and these are prototypical, in that they deal with questions of urbanization somewhere in the world. They are applied in the sense that they tend to be more specifically making recommendations to decision makers, people in civil leadership or in political positions, and we found that after doing a couple of them, every one of them was kind of a start-up, new team, new file-naming convention, a new skill set, etc. The Office is meant to build on those experiences of the Exuma project and the AECOM collaboration on Chinese cities and to then make that kind of capacity more sustainable.

The sustainable Exuma project had as its mandate a kind of three year project to look at urbanization and questions of adaptation to climate change, sea-level rise, and storm event, and also questions of public health. This is in a way a kind of strategic planning. Research leaders looked at correlations between questions of public health and food supply, questions of agricultural availability, the loss of agricultural capacity across the islands at a moment in time. They put in place a series of recommendations. On the one hand those were about public education and around public health, This is in a way a kind of strategic planningknowing that this part of the Exumas has challenges around diabetes and other public health concerns. This involved collaboration with faculty at the GSD but also faculty at the school of public health, and across a range of disciplines on campus. Among other things, it produced a series of recommendations to the Bahamian government and a series of public fora, so a whole variety of community engagements communicating with different audiences, in some cases the traditional conference format or publication. In other contexts, it produced a series of broad page leaflets, and a series of installations in community centers, to communicate to populations that might not otherwise be consuming research products of the GSD.

At this time, have you been able to formulate any specific design strategies for Miami, or is that still a ways off?

We started a year ago with the inaugural project to launch the Office, which was this two and a half year partnership with the city of Miami Beach. Based on the experiences of the sustainable Exuma project, and our experiences with urbanization in China with AECOM, and having made a commitment to build this capacity, to make that capacity sustainable, the focus of the office has been to use design, and design research most notably, as a way of producing knowledge about the world. We thought that beginning with what I think of as the most aggressive, the most challenging condition for climate change in North America, was the right thing to do. That’s where Miami Beach comes in: they have water in the streets on a regular basis. It’s an extraordinary challenge. There’s this very unique condition where it’s got a very singular identity, that part of the world, and its economy/identity in a way is bound up with its architectural heritage. There’s this enormous contradiction on the one hand between having a city that is elevating its streets, building pump stations, building itself up out of sea level rise, and the fact that its identity has been bound up in something so specifically architectural.

We began that project a year ago, so we’re a year into a two and a half year project. This past year we had a group of students and a group of faculty organized in various course work. We had our first event in Miami Beach in February of this year, a colloquium to bring together local knowledge, and we’ve had a team working in the Office over the course of the summer, advancing posing a real challenge intellectually and practically, to the kinds of things the city needs to do in order to adapt to climate changethat knowledge. Coming into this academic year we have one piece which is a real estate field study with professor Richard Peiser that’s looking at real estate development. We have a piece with Gerald Frug, a member of the law faculty, with a law candidate who is studying legal and municipal frameworks. In this context we have a group of students from critical conservation, that’s our conservation stream, looking at the fact that much of the fabric of Miami Beach has been preserved through these heritage and conservation districts, and yet they’re at the wrong elevation. How do you deal with that contradiction? You’ve got a series of listed districts and at the same time we know that the environmental regulations from the 1970s and the preservation districts from the 1980s are directly opposed, posing a real challenge intellectually and practically, to the kinds of things the city needs to do in order to adapt to climate change. We’ll be making our final report in the fall of 2017. We’ll have a public event and a publication, but we have work that is ongoing that is using design to understand these problems.

It’s an interesting case study. One of the reasons we chose that partnership to begin the Office with, beyond my own identity as a native Floridian, was that I liked the fact that by virtue of having one You look at South Florida and you have dozens and dozens of municipalities, and no real effective capacity for regional planning.municipality, the city of Miami Beach, it’s operating in a context that politically it’s difficult to imagine regional or state responses. And so, as we adapt to climate change, increased storm events, sea level rise, there are many examples, in the literature at least it seems clear that the Bay Area’s SPUR (San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association), at the level of regional planning, is really at the forefront in North America. You look at a city like metropolitan New York, and it is arguably among the most well-prepared municipalities at that scale. You look at South Florida and you have dozens and dozens of municipalities, and no real effective capacity for regional planning. You have one mayor who’s been elected on this platform of keeping the streets dry, and is beginning to act in a way unilaterally. Obviously, that’s a unique case, the idea that a city, a mayor, a municipal government would decide to act in response to these challenges in the absence of regional or statewide leadership, that’s a part of what we found so interesting there.

These widespread projects can run into incredible political difficulties. As designers, do you feel that there is an added pressure or emphasis on creating a design that cuts across political boundaries in order to make it effective, and not have it misappropriated or diverted in some way? Or is that something that you worry about down the road?

One of the reasons we thought Miami Beach would be a particularly interesting venue was because it has broken through into the, let’s say, tier of literate journalism. They’ve had pieces in Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair and The New Yorker in the last year or two, there are books underway examining it as the worse case condition. That condition is exacerbated by a long history of water management or mismanagement. In that context, the bigger mandate of the Office is relevant. It’s my perception (and I think it’s a part of my mission in the Office), I think that in our conversations about urbanism today, we tend to end up in one of two places: we either end up arguing or believing that things would be better if only we had better policy. When we talk about urban issues, in many instances it devolves into a conversation about policy. On the other hand, the other equally frequent outcome is that immediately discussions become a one-off negotiation. “Oh, it’s that piece of land. Oh, it’s the Hudson Yards. Oh, it’s the Olympics. Oh, it’s developer x with community y.”

Obviously there are reasons why we’ve ended up in those particular outcomes. But a part of our mandate in the Office is to return to questions of the collective, and to see if there isn’t some room for collective form, and that obviously we’ve explored that in many instances: policy and community and planningThere was a time when we could talk about collective urban form, and that we all somehow have a stake beyond the scale of design. It’s about good governance, and questions around regulatory environments and political input. In the same moment, contemporary urbanism is replete with examples of it being a one-off negotiation. Everything is a deal. A part of the Office is we’re trying to reclaim and re-postulate. There was a time when we could talk about collective urban form, and that we all somehow have a stake, we all have some investment in some implication in collective spatial decision making. That’s my goal. We’ve organized a conference on solar performance and urban form. It’s my assertion, my belief, that we might be on the verge of a new economy of solar performance.

Of course, there’s the old dialectic between capital accumulation through urbanization: think of the metropolis on the one hand, versus questions of social equity and regulatory environments on the other hand. That’s a very old debate. That’s one of the things I like about the topic: it’s ancient. Some of the earliest regulations on buildings in cities both in England and then in the U.S. came out of that tension, let’s say, between capital accumulation through tall buildings and their regulation through regulatory mechanism and urban form. And of course the mythical origin of urban planning with the 1916 zoning ordinance in New York, was as much as anything else about regulating a right to light, let’s say. The whole stepped-back form, towers being a certain set-back, all that stuff. From that point of view, it’s a very old debate, it’s one on the 100th anniversary on the 1916 zoning ordinance we’re returning to, which is looking at heliomorphism.

The new thing, in the recent past, is that prominent architects have proposed a range of different building types and block forms in relationship to solar performance. Two notable examples: Jeanne Gang has recently had approved in New York City a tower she’s calling the Solar Carve tower in the Meatpacking district. This is a building that is the first building that was allowed to have additional height on top in exchange for carving away its midsection to allow light onto the High Line. That’s an example where a leading international architect is using new digital tools to direct solar performance toward certain outcomes, in which case the city was responsive to this and allowed for a given amount of urbanization, a certain amount of FAR, a certain amount of capitalization, to allow sunlight to hit the birds and the bees on the High Line.

At the same exact moment, across town on Roosevelt Island, Morphosis is building the Bloomberg Center, which is the first building on the Cornell Tech campus, and it’s a very large main building that houses a variety of functions. Cornell and Morphosis have agreed that it will be a Net Zero Building. That’s the new economy I’m interested in, one that sits within an ecological urbanism framework.They’re accomplishing this by producing an enormous photovoltaic array on the roof of this building, and the array is actually larger than the building itself. It’s not exactly an aircraft carrier but it’s heading that way, right? Both Thom Mayne and Jeanne Gang are taking the position that they argue is ecological, but they’re doing so in absolutely contradictory ways. One is prioritizing energy production, producing much more shadow, the other is cutting away shadow so as to illuminate the birds and the bees. That’s the new economy I’m interested in, one that sits within an ecological urbanism framework.

So in the Office we want to return to collective questions of urban form. We’ve been working in the school under this broad framework of ecological urbanism and with the heliomorphic/heliotropic/solar performance model, we have something that is zero sum. One person’s shadow is another person’s light. So we’ve seen in the last ten or fifteen years a spate of urbanization across Manhattan. Many of these buildings are optimizing their view and solar access for their tenants. At the same moment, what they haven’t really dealt with as aggressively are far more urban questions: what if all the buildings are making these choices? Is there something possible in the conversation of the collective urban form?

This feature is part of September's Learning theme, considering architectural pedagogy, psychology and more.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

No Comments

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.