How can design be productive in chaotic times? In its latest release "At Extremes," the journal Bracket examines the role of architecture in a world in which "extreme" is constantly being redefined.

Although it is a well-worn trope that the only constant is change, it's also true that some eras are more extreme in that change than others. So how should architecture respond during those moments? The journal Bracket has dedicated an entire issue to exploring not only what "extreme" means, but how the profession as a whole can successfully adapt and even thrive in such an epoch. As the introductory text of the journal notes, "the conditions of extremes demands new tropes: new models of practice, new typologies of buildings, infrastructure and landscapes, and new pairings of program or infrastructure. The question remains: what is the role of architecture or infrastructure in such contexts? to redress? to mitigate? to capitalize on new opportunities?" The journal answers this with a number of projects and essays. A proposed project for a lighthouse in New Zealand called the Awoara is designed to go beyond its traditional function of guidance and become a barometer for all sorts of environmental transformations. Here, authors Nick Roberts, Henry Stephens and Jansen Aui take the long, unpredictable view.

There are few things as fragile or vaunted as the rugged, otherworldly beauty of the New Zealand landscape. The siting of these two slender isles upon a contorted network of cracks and fault-lines has, in spite of its young history of human occupation, unearthed an archaic and unexpectedly singular terrain. Constant geological activity has meant this landscape bears the scars of generations of upheaval, ages would we disrupt an idyllic landscape with a built form, if by its presence we could protect that landscape for posterity?before man — and yet it is now humankind who would prefer this fluctuating landmass held in stasis. Fundamental to the idealized imaginary of New Zealand is a vastly different skyline than the great metropolises of the world. Rather than promote an urbanised vision of architectural progress, it is instead the sea against the hills, the dramatic disjunction of the glacier carved into the high country, the barren Alps of the south that prove so attractive. An unspoken, yet pervasive anxiety over disrupting this natural silhouette is held nation-wide. In proposing a vertical structure designed to protect the landscape, we posited a fundamental architectural choice: would we disrupt an idyllic landscape with a built form, if by its presence we could protect that landscape for posterity? In this regard, we questioned the extremity of human intervention for the sake of preservation.

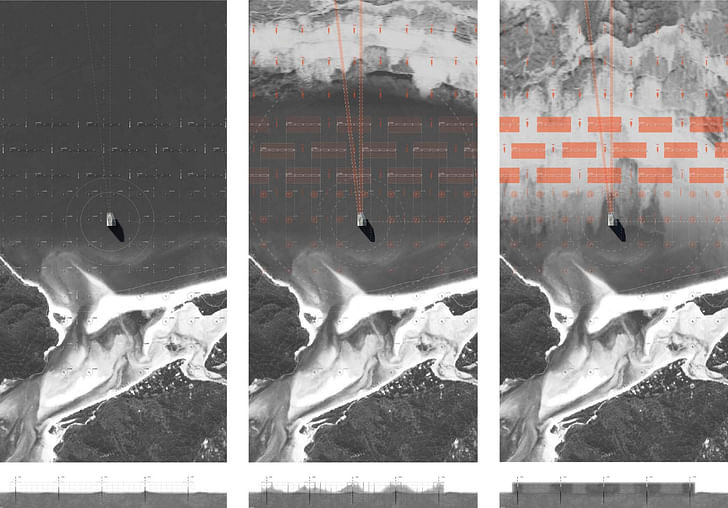

This project is located within New Zealand’s Abel Tasman National Park, an environment that is susceptible to natural disaster. It is an estuary with a constantly shifting profile: tidal patterns, rain and erosion all contribute to a fragile site topography. Acknowledging this, the site also poetically encompasses the conceptual thinking behind the project: there is anxiety over destroying a protected and plainly beautiful natural reserve bearing the very imagery we claim. Looking back at historical building Awaroa Lighthouse proposes a system wherein the forces of architectural intervention and landscape are mutually dependentarchetypes, the lighthouse, so often pictured amidst precipitous coastline and shrouded by violent waters, embodies solidity and stability in its siting. This project seeks to rethink the architectural and iconographic typology of the lighthouse, in this respect. If the traditional lighthouse protected men-at-sea from the threatening, here the lighthouse is positioned as a man-made structure made for protecting the landscape from unpredictable, larger natural forces. By operating across boundaries of destruction, preservation and renewal, an integration between building and landscape is sought. Rather than building on land, or building in land, Awaroa Lighthouse proposes a system wherein the forces of architectural intervention and landscape are mutually dependent.

Functionally, the historical processes of the lighthouse as a navigational, directive, and organizational structure are re-imagined here as a symbol of foresight in the event of an earthquake or related natural disaster. The project expands the traditional lighthouse function by incorporating new monitoring roles; the Awaroa lighthouse records both immaterial data flows from satellite photography from a worldwide network of similarly earthquake-prone sites, and, more locally, seismic data from a network of telemetric rods at the tower’s base. Both of these streams of data are consolidated and interpreted by the lighthouse keeper who resides in the tower. The rods, located at regular intervals across the site, record the constantly shifting landforms of the estuaryThe rods, located at regular intervals across the site, record the constantly shifting landforms of the estuary. A constant feedback loop is created with the lighthouse while a digital topography tracks the real site. When the keepers forecast impending environmental extremes, the architectural system shifts from its passive, ‘recording’ state to its active, ‘protective’ state. The rods beyond the lighthouse assume a denser formation and a previously dormant system within the telemetric rods distributes sand on site into a network of staggered ‘sand walls’ between these outermost rods, defending and preserving the landscape within. The project actively transforms the sand that once made it vulnerable, in order to defend itself.

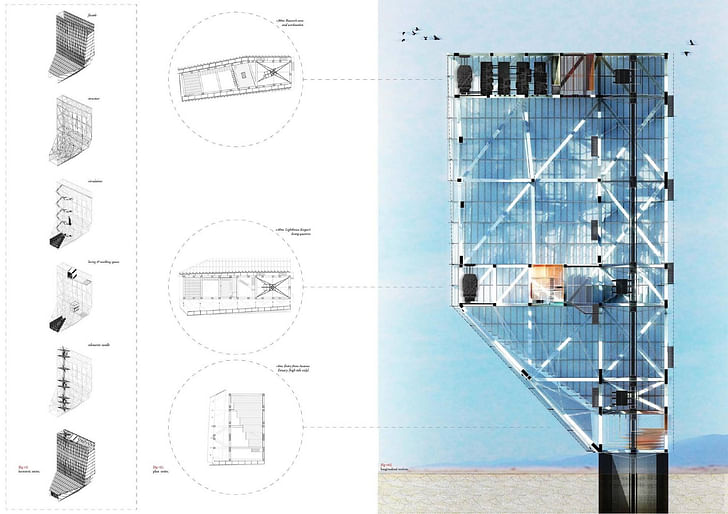

Formally, the tower exposes a play of opposites. Its geometry is designed to look stable, but is in reality fragile. At once austere and monolithic when confronted in one elevation, another view reveals the mass as potentially fragile, susceptible to decay and weather. A play of anchors and cantilevers, interrupted and dislodged views, and disproportionate scale are purposeful absurdities aimed at experientially evoking anxiety. The project is interested in collective emotional notions of architecture and landscape, and imposing a disruptive order to this relationship — always teetering between fragility and hardness.

Over the course of a day, the tower fluctuates between functional and symbolic states. Illuminated from within at night, the structural exoskeleton is revealed. Engaged in both its physical and metaphysical contexts — the lighthouse remains a beacon and symbol, but equally becomes an actor in the landscape, where the endgame is mostly unwritten.

Nick, Henry and Jansen would like to thank Athfield Architects for access to their archives during the production of this project.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Bracket's third issue, "At Extremes", available for purchase on Amazon.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.