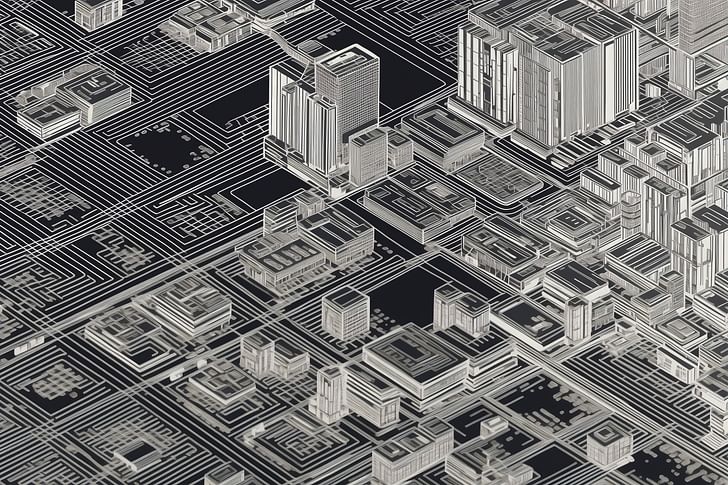

In the final chapter of Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence, Niall Patrick Walsh reflects on the historical relationship between architecture and technology, charting a trajectory for the potential impact of artificial intelligence on the future of the architectural profession. New contributions on the topic from Autodesk's Mike Haley and Superusers author Randy Deutsch are joined by earlier reflections from throughout the series by Richard Saul Wurman, Carlo Ratti, Bjarke Ingels, and Molly Wright Steenson.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

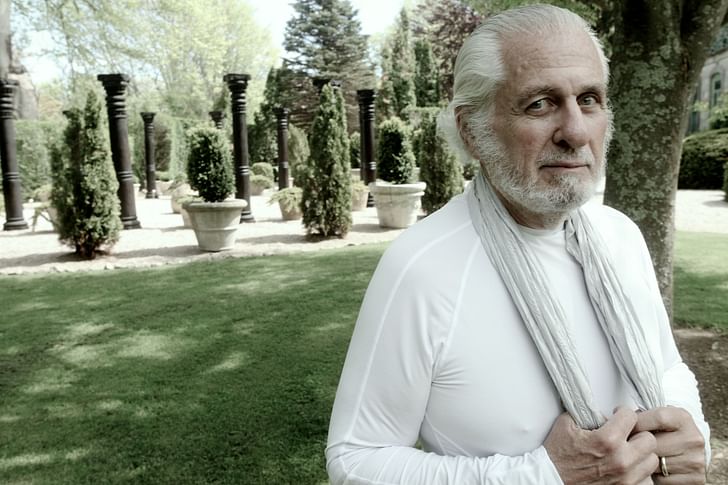

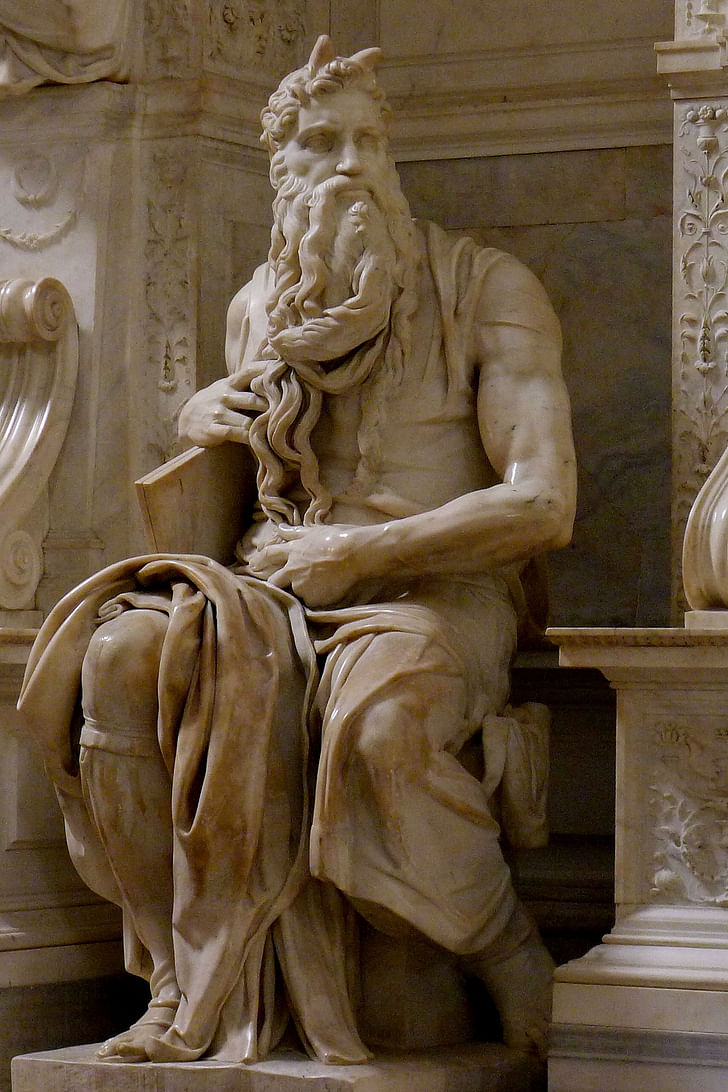

“I love Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses,” TED founder Richard Saul Wurman told me last July. “Moses himself is a larger-than-life character. His life was a fairytale, an exaggeration; he represents a character who goes from swaddling clothes in a river to a king. When Michelangelo was creating his sculpture, he went to Carrara to find marble to use, and he said, 'I have to let Moses out.' To him, Moses was in the stone.”

The question I had asked Wurman was where recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly generative applications from ChatGPT to Midjourney, sit in the hierarchy of tools and technologies Wurman has interacted with across his 70-year career — one deeply interwoven with questions about technology, data, information, and understanding. Michaelangelo’s Moses wasn’t the starting point I was expecting, but the relevance soon became clear.

Incidentally, such unexpected journeys are the highlight, and perhaps defining feature, of my conversations with Wurman. In this one exchange about artificial intelligence, we charted a journey through Moses, the Great Pyramids, cars, Fordlandia, the organization of information, modes of innovation, TED, the Bauhaus, Concorde, Louis Kahn, and Mies van der Rohe, and a plethora of topics from Tina Turner to UK and Irish politics that never found their way into the final article. “Everything is connected,” Wurman reminded me.

We often talk about the cap of where we are in society in the present moment and don’t understand how we got here. — Richard Saul Wurman

But back to AI, via Moses. Through Michaelangelo’s sculpture, Wurman was articulating the connection between technology and creative production. After highlighting the technology required to move the sculpture’s raw marble from Cararra to Rome, Wurman reflected on the technology used to produce the art itself: the hammer and chisel.

“We don’t think about the hammer and chisel as technology because they seem self-evident,” Wurman explained. “But somebody had to invent it, right? If you sent me out to create a hammer and chisel from scratch, whether finding iron ore or heating it correctly, I wouldn’t know how to do it. We often talk about the cap of where we are in society in the present moment and don’t understand how we got here. Nor do we read the usefulness of present inventions in parallel to anything else that has ever been invented.”

Throughout my work on the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series, which spanned 26 feature pieces containing the voices of over 30 experts in the field, two questions were at the forefront of my mind: How has the architectural profession historically been impacted by new technologies, and what will the next chapter in that story, sure to be written about generative AI, look like?

Wurman’s analogy of Moses and the hammer and chisel lays the groundwork for answering our first question. It tells us that the relationship between technology and design is thousands of years old, an observation that led Wurman to create the TED Conference itself, with ‘TED’ derived from the intersection of ‘Technology, Entertainment, and Design.’

This is no less true of architecture, where, throughout history, some of humankind’s most celebrated structures were designed using cutting-edge technology for their time. The Pantheon, Rome’s iconic temple dating from AD 128, owes its longevity to an ultra-durable concrete mixture conceived by the Ancient Romans. Today, the Pantheon remains the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome, while its ‘self-healing’ concrete remains a topic of study by researchers at MIT and Harvard University.

Almost 150 miles north of the Pantheon, and 1,300 years later, Filippo Brunelleschi would invent a series of new technologies to deliver the monumental dome for Florence’s Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, often known simply as the ‘Duomo.’ To construct the dome without internal scaffolding, which would have required more timber than was available in all of central Italy, Brunelleschi invented an ox-driven hoist system to raise heavy stones to their resting place. To ensure marble being transported to the site was not damaged by being moved from boats to carts, he invented an amphibious boat to carry the material across land and water. A host of books have been written about the ingenuity of the design of the Duomo itself, which today remains the largest masonry dome ever built.

Throughout history, some of humankind’s most celebrated structures were designed using cutting-edge technology for their time.

In the late 1800s, meanwhile, as photography first became available to the mass market, Antoni Gaudí would adopt the new technology to ensure sculptures perched high on the Sagrada Familia would not appear distorted or elongated when viewed at an angle from ground level. The innovation undoubtedly came as a relief to Gaudí’s assistants, who, until then, would stand still for hours while full-life casts of them were created for use as sculptures. Such were the grueling demands of the process that one assistant, Richard Opisso, fainted while being cast.

Gaudí’s appropriation of photography is an instructive example of the possibilities unlocked by architects embracing new technologies. The imperative for architects to engage in such experimentation, and its intriguing consequences, was a dominant theme across the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series. “It is important to continuously play with technology to explore its potential,” MIT Senseable City Lab director and 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale curator Carlo Ratti told me. “As architects, we should always play with whatever materials are at our disposal.”

Bjarke Ingels went further, charting how his own gradual embrace of technology across his career has unlocked new paradigms in the design process; a journey that reads like a condensed centuries-long history of the architectural design process itself. “I was drawn to architecture because I loved drawing with crayons and brushes,” Ingels told me last month. “When I started architecture school, I had to learn how to draw with straight-edge rulers. Of course, I loved the sensitivity and freedom I had with crayons and watercolors, but through rulers, I gained the ability to draw multi-point perspectives and isometric drawings; I lost some control but gained a new world of opportunities.”

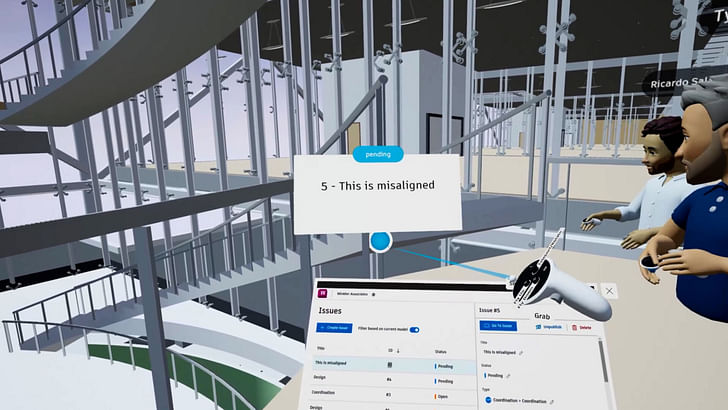

“Then I had to learn to draw with a mouse,” Ingels continued. “I loved the feeling and tactility of a physical drawing using rulers, but the mouse allowed me to create complex 3D models, apply textures, play with daylight settings, and move around in three-dimensional environments. Again, I lost some of the control I was used to but gained a whole new world of possibilities.”

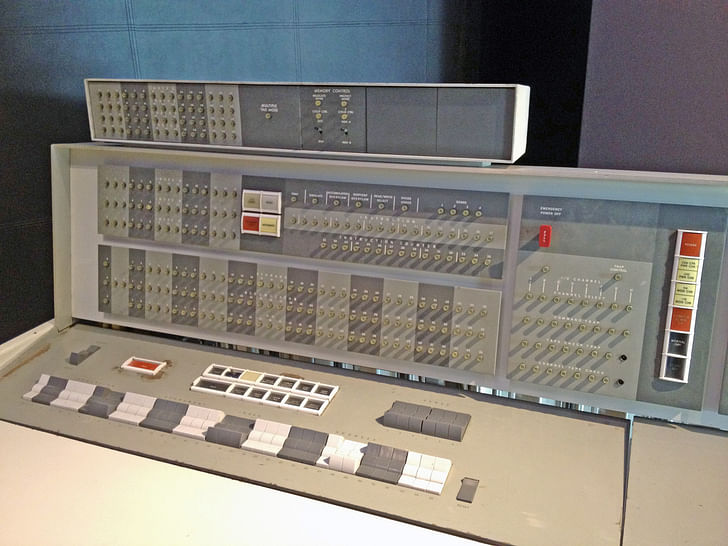

In the relatively short 70-year history of the field of AI, we see a similar relationship between architecture and technology; one built arguably more firmly on reciprocity and interdependence. “People working within AI and computation have always sought out architecture as a way of describing their influence on the world,” designer, educator, and author Molly Wright Steenson told me last July. “AI and architecture needed each other in order to necessitate technological development.”

The relationship between AI and architecture is old enough to receive Social Security in the United States. — Molly Wright Steenson

Steenson cited several examples in support of her thesis. In 1964, she noted, so-called ‘AI godfather’ Marvin Minksy spoke alongside Walter Gropius and Christopher Alexander at the influential Architecture and the Computer conference in Boston, at the same time that Skidmore Owings and Merrill served as early adopters of computer technology alongside MIT and Harvard. In 1970, inventor of the computer mouse Douglas Engelbart proposed the idea of the ‘Augmented Architect’ for the machine age, while architect Nicholas Negroponte’s publication The Architecture Machine: Towards a More Human Environment served as an important reference for the future of computation. Meanwhile, 1976 saw Richard Saul Wurman, who contributed significantly to Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence, coin the field of Information Architecture, instrumental in structuring the World Wide Web.

“The relationship between AI and architecture is old enough to receive Social Security in the United States,” Steenson noted. “It’s part and parcel of the contemporary practice of architecture and architectural modernity.”

Having charted a history of the relationship between architecture and technological innovation, where new technologies have consistently afforded new architectural possibilities, we can address the second question: What will the next chapter look like? Specifically, to what extent will future developments in AI reinforce or upheave the architectural profession’s historic relationship with technology?

For Mike Haley, Senior Vice President of Research at design software leader Autodesk, AI is poised to revolutionize the profession from concept to construction. “It is a crazy time for everybody,” Haley told me in a conversation on the topic. “I think it is a fascinating time for us to figure out how we adopt all of these technologies.”

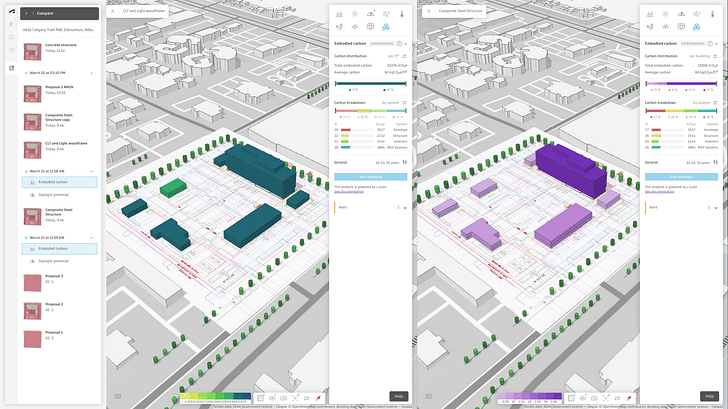

Like many software companies, large and small, Autodesk has thrown itself into the potential of AI to transform its target sector. In May 2023, Autodesk unveiled Forma, a flagship AI-driven tool for the AEC sector capable of generating and analyzing early-stage BIM models, followed one year later by the launch of an AI-powered embodied carbon tool to be embedded within Forma. In November 2023, meanwhile, the company used its Autodesk University expo to introduce Autodesk AI, an umbrella concept to describe the company’s goal of using AI to strengthen collaboration across its architecture, engineering, construction, media, entertainment, and manufacturing software platforms.

Related on Archinect: Autodesk unveils Forma, an AI-driven tool for generating and analyzing BIM models. Video by Autodesk

As a side note, the prevailing observation from my own visit to Autodesk University in November 2023 was the seemingly endless array of architects, engineers, and technologists showcasing AI-driven solutions for all aspects of the design and construction process, from lifecycle carbon assessments to geospatial mapping, or HVAC design to construction quality control. It is no exaggeration to say that among the close-to 200 exhibitors at the event, AI was the talk of the town.

Autodesk’s emphasis on the potential for AI in the built environment is no less strong in Haley’s team, which, in his own words, is “the only team in Autodesk whose charter is to stay three to ten years ahead of the wider company.” Reflecting on the daily work of architects in the near future, Haley presented me with three areas where AI will play an outsized role. The first is ‘human-computer interaction,’ where the experience of ‘talking’ to a computer moves towards that of talking to a human. As Haley pointed out, the seeds of this relationship have been sown for over a decade with the advent of virtual voice-command assistants such as Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa or, more recently, command-driven AI tools such as ChatGPT and Midjourney.

“We can give sketches and images to a system and say ‘Make my image look like this,’” Haley told me. “If you think about it, it isn’t too far from how we interact with another person. If you are redesigning your kitchen, you would sit at the table with the architect, pick pictures out of magazines, sketch something, and have a conversation. The architect will interpret that and produce drawings for your kitchen remodel. I have a whole group of researchers spending a significant amount of time moving software in this direction.”

The construction industry can be a messy environment that is constantly changing, so having these tools that can feasibly understand that environment and absorb it, is a huge development. — Mike Haley

Haley’s second identified impact of AI, ‘capturing the state of the world,’ rests on AI’s growing ability to digest and interpret data collected from the built environment, from humans to buildings to weather conditions; a capability central to my recent feature ‘The People’s Place in the City of Bits and Atoms.’ Outlining the potential applications of such data processing, Haley cites a colleague of his in Autodesk working on a startup that uses AI to scan the outside of buildings in developing countries to determine structural issues that could become hazardous during an earthquake.

“The AI can judge that maybe there aren’t the right supporting beams, or the foundation isn’t built correctly, and so on,” Haley continued. “This is one example where it would be difficult for a human to pick these issues up rapidly by themselves. AI, on the other hand, can be trained to do it. The construction industry can be a messy environment that is constantly changing, so having these tools that can feasibly understand that environment and absorb it, is a huge development.”

The third impact of AI described by Haley revolves around ‘reasoning,’ building on the emerging ability of generative AI systems to reason across multiple modalities such as video, imagery, sound, and text. At Autodesk, the work of Haley’s team in this field revolves around overcoming the much-reported error-prone nature of generative AI models, using detailed simulations of real-world conditions to produce models whose output is not only aesthetically striking but accurate.

“We are trying to create a world where these two sides of generative AI, creative freedom and precision, are brought together,” Haley told me. “Our goal is that software users can freely express themselves in a generative AI experience as well as accurately explore solutions within realistic contexts and conditions. I think we will see this in the coming years: AI reasoning systems that are accurately connected to the real world.”

In the architectural office of the future, being an expert won’t be about knowing what buttons to press, because the ability to express yourself through software will be intrinsic. — Mike Haley

Throughout the history of the architecture studio, every consequential new technology has brought with it a shift in the function of human architects. Young computational designers today may look with awe at greyscale photographs of armies of drawing boards, paper rolls, and draftspeople occupying the architecture studios of the 1950s; draftspeople who no doubt looked back in similar awe at Gaudí’s chaotic plant-strewn workshop in the Sagrada Familia from 1900. For Haley, AI will similarly herald a new relationship between humans and design apparatus in tomorrow’s architecture studio.

“In the architectural office of the future, being an expert won’t be about knowing what buttons to press, because the ability to express yourself through software will be intrinsic,” Haley told me. “It will become more accessible by definition. As a result, we will be able to train more people to realize visions. If you’re not great at computers but are a brilliant architectural thinker, the software will increasingly be an effective companion or assistant to your work, better able to interpret your desires.”

“There is going to be an evolution where the most successful designers and creators will be those who have learned how to interface with these tools, and those who can bring complementary skills that the tool does not possess, instead of trying to compete with a role the tool is already performing,” Haley added.

What might these complementary skills be? For Randy Deutsch, an architect and Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the answer lies in the archetype of the ‘superuser,’ a persona Deutsch described in his 2019 book Superusers: Design Technology Specialists and the Future of Practice.

“Superusers are design professionals with the wherewithal to recognize a tool, curiosity to inquire into a tool, confidence to mess with a tool, capacity to learn from a tool, creativity to combine tools, and the interpersonal intelligence to connect with others to achieve actionable results,” Deutsch writes in the book.

For Deutsch, the defining qualities enabling superusers to surf the wave of increasingly capable AI tools are summed up in ten ‘C-factors’: curiosity, contextualizers, connectors, communicators, collaborators, capacitors, continual improvers, concentrators, computational thinkers, and coders. In a conversation with me on the topic, Deutsch highlighted the fact that despite the initial assumption of some that a superuser must be primarily technically based, nine of his ten C-factors are soft skills, mindsets, and attitudes, with only ‘coding’ demanding deep technical ability.

“A superuser is somebody who connects the business needs of an organization with technology solutions,” Deutsch told me. “This is not necessarily the IT folk. In fact, it’s the opposite. Superusers are integrated into teams to understand what problems need solving. More importantly, they are problem identifiers, not just problem solvers. They redefine everything they’re given to do in terms of delivering value, whether business value, building performance value, or design excellence value.”

What we are losing sight of too frequently in architecture is finding the tool of choice. We tend to be hammers that look at every problem as a nail. — Randy Deutsch

Five years after its publication, Deutsch’s book and wider superuser concept align with the vision set out by Autodesk’s Haley, where the value of the ‘expert’ human architect will lie not in a deep technical knowledge of a particular software but in the motivation and curiosity to continually explore, exploit, and appropriate an ever-growing selection of ever-more intuitive digital tools and apps aimed at the AEC sector.

“Even in 2019, AI was clearly on the horizon,” Deutsch recalled. “Arriving at where we are today, I am pleasantly surprised by how intuitive these tools are to use. You don’t have to be a professional to pick these tools up and play with them. This is one of the qualities of the superuser: Somebody with the wherewithal and capacity to pick up any tool and play with it.”

“A superuser thinks of this new wave of software and apps as tools in their toolbox that also includes pens, notebooks, tracing paper, or whatever tool is best in any given situation,” Deutsch continued. “What we are losing sight of too frequently in architecture is finding the tool of choice. We tend to be hammers that look at every problem as a nail. A superuser is able to take a deep breath and ask themselves what is the best approach to tackling a given situation. On the technology side, that might involve outsourcing a task, purchasing and learning a new tool, or coming up with their own tool.”

In thoughts or conversations about AI, I often remind myself of Amara’s Law, devised by American scientist and futurist Roy Amara: “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” Throughout the past two years, humanity has been firmly in the grips of an AI hype cycle, with an endless supply of news articles, keynote speeches, and tweets predicting the incoming imminent implosion of industries at the hands of our new AI overlords. The frenzy is not surprising; technology hype cycles can make fortunes for the loudest voices on newsfeeds, stages, and Twitter Spaces.

Such frenzied concerns over the near future prospects of human architects were largely absent from the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series. To the dozens of architects, educators, and technologists who lent their voices to the series, the message echoed that of Haley and Deutsch: The near future holds promise for architects who embrace AI as a collaborator as opposed to a competitor. Where the word ‘replacement’ arose, it was often in the context of the phrase: ‘AI will not replace architects, but architects who use AI will replace those who do not.’

In thoughts or conversations about AI, I often remind myself of Amara’s Law, devised by American scientist and futurist Roy Amara: “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

But what of the long run? In the first article of Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence, I quoted the physicist and Nobel laureate Niels Bohr, who said: “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” This still holds true at the end of the series.

In a positive reading of the far future, the ever-increasing capabilities of AI in pattern recognition and data processing present a largely unexplored opportunity for architects to articulate, codify, and quantify the value of their profession; one tasked with servicing a variety of sometimes conflicting agendas from clients, designers, builders, the public, and the environment.

“The architect,” writes series contributor Phil Bernstein about a tangential opportunity in his book Machine Learning: Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, “either generates, reviews, or is subject to the implications of the vast amounts of information that swirl around even a simple building enterprise. That information, despite efforts to rigorously standardize it, manifests in a wide variety of formats, versions, and levels of detail... An immediate opportunity of AI — one that is yet unexplored — would be to try to ‘understand’ the relationships between these data and help deploy them in a structured, accessible, and efficient manner.”

In a more extreme pessimistic reading of the far future, AI could destroy the profession. As Richard and Daniel Susskind outline in their book The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform The Future of Human Experts, society has traditionally placed trust in the professions to deliver services and activities; trust that is derived from formalized expertise, experience, and judgment. If future AI systems reach such a level of expertise, experience, and judgment, informed by a command of building codes, real-time environmental data, and previous project learnings that a human architect could never hope to match, will preferential public trust in the human professional survive?

“(We) argue that the professions will undergo two parallel sets of changes,” Susskind and Susskind write. “The first will be dominated by automation. Traditional ways of working will be streamlined and optimized through the application of technology. The second will be dominated by innovation. Increasingly capable systems will transform the work of professionals, giving birth to new ways of sharing practical expertise. In the long run, the second future will prevail, and our professions will be dismantled incrementally.”

We must also remind ourselves that architects do not exist in a vacuum. The capitalist economic system in which architecture operates is grounded in an equilibrium between the supply and demand of human labor. In a future where AI systems disrupt such a balance, replacing or diminishing human responsibility for the production of services and products, our profession itself does not need to be directly replaced or diminished in order to feel the impact of such disruption, be it the unaffordability of architectural services, social unrest, or growing inequality.

Whether the intelligence governing the design and delivery of that shelter in the far future will be human or non-human depends on too many unpredictable variables and future innovations, from hardware and software to regulation to human psychology. The architect's ability to operate laterally across such fields is indispensable to that question, if we choose to engage.

For such a future to manifest, AI would need to break the thesis set out in the first part of this article, where advances in technology afford new possibilities for architects to exploit in the design and delivery of built environments. Importantly, this would not break the thesis that new technologies afford new possibilities for the delivery of architecture. Humans will always need shelter, and a means of production to deliver such shelter. Whether the intelligence governing the design and delivery of that shelter in the far future will be human or non-human depends on too many unpredictable variables and future innovations, from hardware and software to regulation to human psychology. The architect's ability to operate laterally across such fields is indispensable to that question, if we choose to engage.

In the meantime, I will close this series with two tentative observations about the likely impact of AI on the long-term future of the architectural profession.

The first observation is elemental but is nonetheless important to remember in the current hype cycle: AI is not the only future of the architectural profession. As an analogy, Apple’s 1984 unveiling of the Macintosh during Super Bowl XVIII undoubtedly caused some architects to declare: “Computers are the future of the profession.” Computers would indeed play a major role in the future of the profession, and will continue to do so, but they did not do so alone. In the United Kingdom, one could make the argument that in the 1980s, Margret Thatcher’s destruction of both public architecture departments and mandatory minimum fee scales was just as impactful on the architectural profession as Steve Jobs' innovative products. As we look further into the 21st century, advances in AI will likewise constitute only one force shaping how architects work and what they design, joined and perhaps dwarfed by hitherto unknown advances in material science, construction methods, housing policies, climate events, geopolitical realignment, extraterrestrial habitats, and more.

Apple's 1984 advert introducing the Macintosh

The second observation echoes the first, albeit at a more zoomed-in scale: there is no singular future of AI in the architectural profession. The future of AI in the profession will instead be made up of a wide variety of constituent futures, as architects and non-architects alike exploit their era’s AI capabilities using the built environment as their subject. Like 21st-century Gaudís and Brunelleschis, some architects may use AI as a means to invent novel ways of delivering record-breaking structures, while the solo practitioner may enjoy a renaissance where individual architects harness the collective knowledge of an entire profession through a suite of AI assistants, designing for physical and virtual environments alike.

Others may move beyond the design of buildings, using AI as a vehicle to build apps, tools, and support infrastructure, or as a design medium to address systemic issues in the built environment. Our series has already met early adopters of this approach, including Behnaz Farahi’s use of AI in fashion design to interrogate surveillance, Felecia Davis’ use of AI in sculpture to interrogate racism and discrimination, or ecoLogicStudio’s use of AI in ecology to interrogate climate change.

The future of AI in the profession will instead be made up of a wide variety of constituent futures, as architects and non-architects alike exploit their era’s AI capabilities using the built environment as their subject.

Elsewhere, there may be an explosion in the variety of machine learning models, as large, established, multinational architecture firms each choose to develop their own in-house models rather than surrendering decades of intellectual property to third-party companies such as Google or OpenAI. Conversely, other architecture firms may not deliver buildings at all but exist solely as a source of high-quality building design drawings, models, and data to be licensed to external companies, but only at the right price. There may be rogue architectural actors who specialize in design data theft and starchitect forgery, met by adversaries who merge skills in architecture, law, and technology to investigate and prevent theft of data or breaches of copyright.

“Michelangelo could have taken that hammer and chisel and turned it on his assistants in violence,” Wurman reminded me. “Instead, he used it to create a masterpiece. The lesson here is that many wonderful inventions can be used in many ways.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

3 Comments

Autodesk's ad looks intereting, but comparing Michelangelo's technologically primitive hammer and chisel to the possiblilities of this technology is hillarious and disengenious. Michelangelo's work was a product of a trained eye as well as his skill with tools, something no amount of AI can duplicate.

Great summary.

@Thayer, that does seem to be the point (that AI is a tool, to be used with skill, the way Michelangelo used chisel and hammer). So, not disingenuous. But maybe it sidesteps the issue too quickly.

The way AI is built right now, the role of creativity and creation is probably the thing we fear losing control over the most. It is certainly where all the lawsuits are lining up. And for good reason.

A framework that is useful to me recently when looking at AI is to imagine knowledge and creation as the literal infrastructure of an AI based future. Without new material being added to the system AI will necessarily have an in-built cap that makes it less useful (and less interesting) than promised. So where does that information come from and who is being paid for it is pretty important as questions go. The tool-ness of AI is less important by comparison.

If we do go all in to the AI future our role as creatives may be simply to feed the new infrastructure of information. Human knowledge and creativity itself are the utility in that scenario, like water and electricity are today. In that world our relationship with creativity will have to change. It is surreal to imagine, but when/if it happens, what do creatives do? Do we take profit and pleasure from feeding a system, and get paid for adding fuel to the fire every once in a while? How does the economics of that world even work? Will we be the tool users or the material that tools are made from?

Based on where AI is at right now this question is too early and probably paranoid, but if AI grows exponentially like Dario Amodei is proposing, then it will become a question we will all answer pretty soon. One way or another...

Will, I'm not discounting AI's potential, nor do I fear it, just observing that this kind of techno utopianism is the same one modernists employed to sell their dystopian vision. FWIW, this is the sentence which is hillarious.

Michelangelo could have taken that hammer and chisel and turned it on his assistants in violence Instead, he used it to create a masterpiece.The lesson here is that many wonderful inventions can be used in many ways

The key to those masterpieces wasn't the tool, but the years of work required to design and craft beautifully, something no amount of computing horsepower will ever replace. I guess we'll agree to disagree as usual :)

Btw, I like the black classical columns and the cult leader stare. Maybe he should use AI to change his branding.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.