As a ‘Space Architect’ working on the design and delivery of 3D printed habitats on the Moon and Mars, Melodie Yashar is aware that, even in space, 3D printing does not exist in a vacuum. Like any construction methodology, it requires a confluence of design intent, delivery systems, material science, and accessible economics.

In her role as Vice President of Building Design & Performance at the construction technologies company ICON, Yashar is overseeing the design and implementation of products across all these fields, with an immediate primary goal of establishing a more affordable and sustainable design and construction system. As Yashar outlined in her 2022 TED Talk, the lessons learned from such ambitious endeavors here on Earth can spark lines of inquiry for perhaps humanity’s ultimate unresolved ambitious endeavor: surviving and thriving beyond Earth itself.

Last week, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Yashar as ICON was in the process of unveiling a suite of new technologies and products spanning 3D printers, home catalogs, material science, and artificial intelligence. In addition to gaining a behind-the-scenes look at ICON’s work here on Earth, we discuss the applicability of such technologies to Yashar’s work beyond our planet. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: There are four technologies that ICON recently announced, so let’s start with your new 3D printer, Phoenix. We often report on 3D printed projects, and the vast majority are single-story structures. From the outside, the most significant innovation of Phoenix appears to be that it supports multi-story printing. Could you give us an insight into how the printer differs from its single-story predecessors, such as ICON’s own Vulcan printer?

Melodie Yashar: The differences in form factor between Vulcan and Phoenix define new opportunities for Phoenix and multi-story printing. This applies to both the building’s design and the construction operations required to build with these systems. Vulcan was designed for single-family detached housing and operates on rails. This is well-suited for single-story projects, where you can print linearly and create a grid-like economy of scale. The result is large communities that could be delivered in short order.

The design of Phoenix is completely different. Phoenix is essentially a robotic arm that enables us to print up to a certain reach distance and at a much taller height, up to 27 feet. This is our first foray into considering how we print the full enclosure of a building without stopping — including foundations, wall systems, and the roof system, which we hadn’t done with Vulcan.

Phoenix’s form factor also has ramifications for construction site activities. When you are operating at 27 feet, at more than one story off the ground, you have to think more about scaffolding, shoring, how you’ll perform wall inspections, and how you’ll incorporate other standard materials needed to complete the wall assembly and enclose the building. We’ve started exploring this new construction operations workflow with our House of Phoenix mockup, which was preceded by substantial schematic and concept-level architectural iteration, and of course, that will serve as a model that we will continue to prototype and develop.

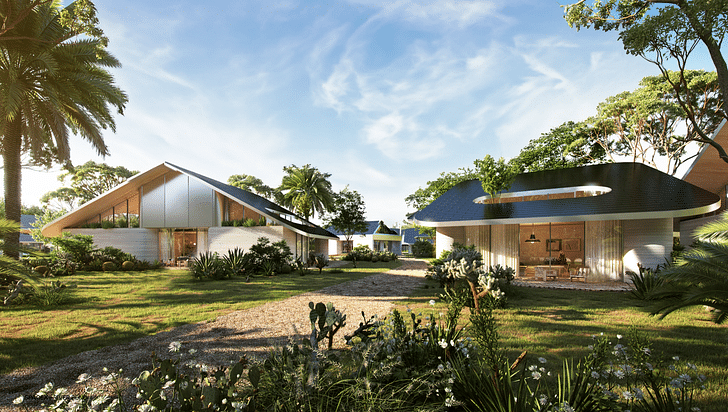

Moving on to CODEX then, your new catalog of 3D printed housing units. So far, you have included 60 ready-to-print homes in five collections and have developed a process where architects can submit designs for consideration as the catalog grows. This places you in the role of ‘curator’ in some ways. What principles or criteria are going to govern what designs do and do not get included in the collection, given the wide variety of design solutions architects are likely to generate for 3D printed homes?

As of yet, construction-scale 3D printing hasn’t been democratized the way that desktop 3D printing has. Not many architects have worked with the technology, and it isn’t exactly widespread across the building sector. CODEX is our way of introducing an opportunity for architects to more closely engage our technology by providing a platform for designers interested in providing 3D printed design solutions for the housing market. With the release of CODEX, we are releasing an “Architect’s Handbook,” which details how to design and build with our technology. We hope that architects will take this as an opportunity to pitch ideas so we can form a broader and more diverse vision of what is possible using 3D printing because, today, we’ve only scratched the surface.

We hope that architects will take this as an opportunity to pitch ideas so we can form a broader and more diverse vision of what is possible using 3D printing because, today, we’ve only scratched the surface. — Melodie Yashar

We formulated the initial collections of the catalog based on particular performance advantages we’ve identified with our system and which our customers have told us are meaningful to them. For example, the storm and fire collections respond to specific environmental performance criteria that our customers, such as developers and builders, have identified as being important. The intention is that you can design a house in the Southwest, Northwest, or Gulf Coast of Texas that is environmentally appropriate to that region. As more adopt the technology, we are hoping to see more people bring ideas to the table for the kind of architecture that is most regionally appropriate for them and their unique region or climate zone.

With CODEX, there is also the suggestion of a new business model for architects. Some have written that the future of the professions, architecture included, is one where the professions move from service-centric to product-centric. Our typical model has been to bill clients per hour or as a percentage fee as we develop a bespoke solution; focusing on servicing one client at any given time. You are instead adopting an approach where architects are paid for pre-designed products that appear in the catalog, which sets up a new relationship between the architect, developer, fabricator, and client. Was the need for a new architectural business model something that you dwelled on much when designing your catalog process?

It was extremely intentional. The idea of being a patron to an architect on a design process for a home that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars is not financially feasible for most, and very few homeowners have the opportunity or the means to design their own residence with an architect. We are heavily invested in resolving the global housing crisis, but we do not believe that we must compromise on architecture and design when introducing growth into the housing sector. CODEX is about introducing beautiful and dignified housing solutions that are affordable and reachable to consumers and home buyers at multiple price points.

The idea of being a patron to an architect on a design process for a home that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars is not financially feasible for most, and very few homeowners have the opportunity or the means to design their own residence with an architect. — Melodie Yashar

Robotic construction processes such as 3D printed construction can introduce rapid growth into the housing sector, so it doesn’t make sense to purpose-design every single home on every single site, as might happen in the traditional architectural service model. We see CODEX as a platform as well as a starting point; it is a catalog of offerings for homeowners and developers to choose from, which will, over time, expand based on consumer interests and needs, as well as the new design vision that designers and architects globally bring to the table.

Alongside Phoenix and CODEX, you’ve also announced CarbonX, a concrete formula for 3D printing. We often report on material science innovations in 3D printing, with fascinating cocktails of ingredients from algae to recycled materials to earth. What were the specific principles or intentions behind the development of CarbonX?

The main goal behind CarbonX was to introduce a material with significantly less embodied carbon as compared with standard concrete but without comprising on performance. We have already developed a building material for printing called Lavacrete, which was used in Vulcan, and CarbonX has been developed to be as strong, if not stronger. When developing CarbonX, it was also important for us to design for deployment at scale so that we can realize projects at an industrial scale beyond the lab. Essentially, CarbonX is not just a research investigation but will be our material of choice for our construction project moving forward.

To what extent did that involve interacting with building codes? Was CarbonX novel enough that it required extensive building code testing, or was it more conventional?

This is what the bulk of our architecture and building performance department coordinates. We have certifications for our wall system, materials, and printing system, all of which exist using our prior Lavacrete material. Part of the challenge when working with regulatory bodies is to establish equivalency between our prior work, including destructive testing and engineering analysis, and our new material.

The main goal behind CarbonX was to introduce a material with significantly less embodied carbon as compared with standard concrete, but without comprising on performance. — Melodie Yashar

There are certain tests that we duplicate and replicate all the time, such as testing the strength of small cylinder samples and measuring flexural strength. But it is a whole other level to undergo destructive testing on full-scale wall samples that are 10 feet tall, including shipping them out of the lab and having them destroyed in a particular environment. Hence, we try to be strategic about how often we carry out full-scale testing, given it is such a huge investment. Thus far, our engineering has been able to establish equivalency with prior work in the cases that may have required testing.

That’s a shame. Destructive testing would make for great TikTok content. The final product you recently announced is Vitruvius, which you describe as “an AI system for designing and building homes.” Was Vitruvius developed in similar ways to large language models such as GPT-4, which was trained on vast amounts of text and image data, to develop the ability to produce design solutions, or did it take a different approach?

It was quite similar. The training data for Vitruvius was essentially a database of architectural home designs by us and our partners, which we have steadily assembled over time. It is a pretty significant and substantial database. Vitruvius itself was built on open-source tools and APIs, so yes, it incorporates a large language model as the primary interface for humans to interact with.

Launching Vitruvius is exciting, but I also believe we are just at the beginning. It has been interesting to observe how much of an impact the training data has on the results or outcomes that Vitruvius produces. It is certainly something we will continue to iterate and expand upon.

At Archinect, we have undertaken an extensive editorial series on artificial intelligence, and an omnipresent question throughout the conversations we have had is: What is the future relationship between AI design systems and human architects?

I’m aware that there is no definitive answer to that question, and it is governed by so many factors, but do you have a vision for what the relationship between Vitruvius and human architects will be? Will Vitruvius be a collaborator for human architects, or could it bypass human architects altogether and be used directly by a client or catalog user?

I am an architect and designer myself, so I may be biased, but I do not feel threatened that AI will eliminate or diminish the role of an architect. However, I do believe that the role of the architect will significantly change with the availability of AI tools and resources. There is no reason to think that we are going to work in the same way as we did before. That is just not going to be the case.

There is no reason to think that we are going to work in the same way as we did before. — Melodie Yashar

At the moment, Vitruvius is extremely powerful, provocative, and inspiring in how quickly it can allow us to iterate on concept-level proposals. That said, there are so many technicalities to architecture, such as building sensitivities in certain jurisdictions, weatherization, performance standards, and so on. We have a long way to go before these are fully resolved within an AI-powered architecture system. There is a large amount of room and flexibility for us to not only develop tools with this embodied intelligence but to also ask what the role of the human architect is with respect to these systems, which may be ignorant of values that are important in the creation and realization of architecture.

Before we conclude, I wanted to ask some extraterrestrial questions. You gave a TED Talk in 2022 where you reflected on how designing habitats on the Moon and Mars teaches you so much about designing here on Earth, and vice versa. Is there anything in the products and technologies we have discussed today that you believe could further the cause of building beyond Earth?

It’s hard to know where to start! The truth is that all these discussions are intimately related — but particularly in regards to the highly efficient design methodology needed to think about designing for off-world systems in a resource-constrained and hostile environment, which parallels the urgency with which we are trying to introduce more sustainable, economical, and affordable means of construction here on Earth.

For designing in space, there are significant technology gaps, gaps in our understanding, and gaps in research, all of which require further development, and for which we simply don’t have the answers right now. There is no large-scale additive manufacturing happening in space, at least not yet. The closest alternative we, therefore, have, which we are doing daily here on Earth, is to realize these structures at a human scale terrestrially.

There is no large-scale additive manufacturing happening in space, at least not yet. — Melodie Yashar

When we were developing Mars Dune Alpha (the Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog), for example, NASA was curious about how we could resolve the interface between the door of the habitat and the airlock to the Martian surface. They were asking if we could iterate on the solution and use it as an opportunity to learn and make progress from a research perspective on a possible solution applicable to a Mars context. The truth is that, with every home we finish here on Earth, we are learning and iterating. We learn about waterproofing and weatherization principles, material durability, repairability, maintainability, thermal comfort, energy efficiency, and even how homeowners interact with and manage their homes throughout the building’s lifecycle.

We are just at the beginning of collecting this kind of data, which I think will be transformative not only for understanding a new way of building here on Earth but will also teach us about the ramifications and sensitivities required to translate this into an off-world scenario, where the risks to human safety are just so much greater.

When I think about what it is like to design habitats on the Moon and Mars, I imagine it being a see-saw. On one side, you have extremely micro, in-depth engineering questions and constraints that cause you to become absorbed in the weeds of physics and chemistry. But on the other side, you are intersecting with massive, macro, existential questions about what humanity wants to be beyond Earth. I don’t think there is any other topic that evokes such a sense of universal excitement or childlike wonder. Does this see-saw ever come into play? Or is it more effective for you to focus on the micro, where at least one person can quantify the task at hand?

What you are describing, to me, is the challenge of being either a subject matter specialist or a generalist in considering solutions to 3D printed habitats. The truth is that when it comes to off-world habitats, the field is at such an early stage that there is no single authority, not even NASA. No one person has done this a hundred times and uncovered the tried-and-true methods for how to create these environments. This applies across the board, from a structural perspective to a technology delivery and deployment perspective to a materials perspective. These are all disparate fields and disciplines that need to collaborate and communicate with each other.

I have learned to keep an open mind, to be sure that the right people are at the table at the right time, and to ensure we are not becoming siloed in our opinions about how to solve a problem. — Melodie Yashar

I have found that to work effectively in this field, you need to solicit and work with the right person for the right task — recognizing that there is no singular authority on design strategies for off-world habitats and, similarly, that 3D printed habitats represent a true confluence of fields. Intentional transdisciplinary collaboration tends not to happen in singular large corporations without sufficient time and budgetary resources. If we are designing 3D printed materials, we need to talk to planetary scientists and in situ resource utilization experts. If we are talking about the ramifications of large-scale resource utilization, we need to talk to space lawyers, non-profits, and specialists who study the ramifications of commercial resource utilization at a planetary scale. There are already groups anticipating large-scale systemic questions for off-Earth habitats, from land use to common law.

The most important thing, from my perspective, for me is to maintain a willingness to learn and listen to others from disparate fields that I know nothing about. I have learned to keep an open mind, to be sure that the right people are at the table at the right time, and to ensure we are not becoming siloed in our opinions about how to solve a problem.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.