The city of the 21st century represents a confluence of bits and atoms; an organism in its own right that relentlessly spawns information and data about itself, its people, and the invisible flows that support them. What is the relationship between humans and the city in this new condition? What is its future? To explore these questions, we speak with architect, TED founder, and father of information architecture Richard Saul Wurman, 2025 Venice Biennale curator Carlo Ratti, and MIT Media Lab researchers Naroa Coretti and Ainhoa Genua.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

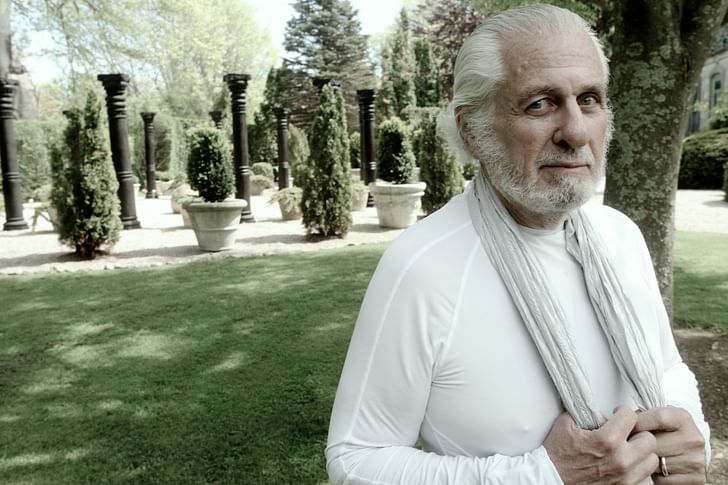

In 1976, Richard Saul Wurman chaired the national AIA Convention in Philadelphia. Operating under the convention theme ‘The American City: The Architecture of Information,’ Wurman set out a vision for cities built upon the relationship between urbanism, information, and people.

“Wouldn’t a city – any city – be more useful and more fun if everybody knew what to do in it, and with it?” the conference brochure asked. “As architects, we know it takes more than good-looking buildings to make a city habitable and usable. It takes information: information about what spaces do as well as how they look; information that helps people articulate their needs and respond to change. That’s what Architecture of Information is all about.”

Almost fifty years later, in a recent conversation with Wurman, I returned to the 1976 brochure with a mission of exploring how prevailing approaches to urban planning have, or have not, lived up to Wurman’s vision. As someone whose lifelong pursuit of ‘understanding’ includes founding the TED conference, pioneering the field of Information Architecture, and formulating organizational theories such as LATCH and A-NOSE, it is perhaps no surprise that Wurman’s views on urbanism emphasize the potential for cities as places of learning and understanding.

“If you understand everything that goes on in the city, you don't have to go to school,” Wurman told me. “What and why you do everything, where you do it, what things do, how they are made and fabricated, how they are sold, and how people interact with each other, all happens in the city. If you can understand that, why go to school? You already have everything. The city is a schoolhouse.”

“You can turn the dial up even further,” Wurman continued. “On the ground floor of every building that has more than one shop window, you can allocate only one window to advertising or personal use. Every other window must contain information about how something in the store is made, be it a dress or a shoe or so on. Tell us about what you have in there, and how it came to be. Outside, as you walk down the street, you are always learning. I’ve called this idea ‘Wait Watchers’. Whether you are waiting for a bus, or a subway, or to enter a restaurant, or even walking down a street, you can have an interesting time on the ground floor of the city.”

If you understand everything that goes on in the city, you don't have to go to school. — Richard Saul Wurman

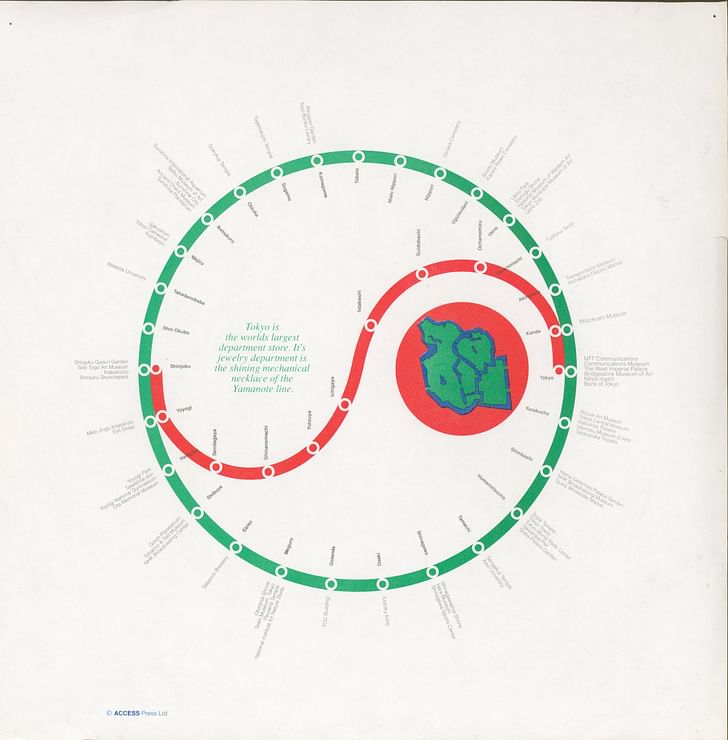

A vision of cities as environments for learning and understanding permeates Wurman’s career. In his 1971 volume of Design Quarterly, titled ‘Making The City Observable,’ Wurman wrote: “Public information should be made public. Information about our urban environment should be made understandable. Architects, planners, and designers should commit themselves to making their ideas immediately comprehensible. Making the city observable implies allowing the city to become an environment for learning.” In 1980, he published the first in a series of Access guides which, in Molly Wright Steenson’s words, saw urban maps not just as “a guide to the city” but “a means of access.” In 2013, meanwhile, Wurman collaborated with ESRI and RadicalMedia on the urbanobservatory.org platform which, in its own words, “aims to make the world’s data both understandable and useful.” Now in 2024, I asked Wurman how today's prevailing approaches to urban planning measure against his own.

“If you work backward from the city being a schoolhouse: shitty,” Wurman replied. “If you visit Hudson Yards, which was designed by talented architects, the ground floor is horrible. They put a horrible sculpture in the middle, which is even worse now since it isn’t being used. I hope it rusts away. It was ugly before it went up and it’s ugly now. Is this the way we think a city should be?”

“When you walk around a city, your central field of vision is 30 degrees above your line of sight, and 30 degrees below it,” Wurman elaborated. “In other words, we look slightly up and slightly down so that we don’t hit our heads or trip our feet. Nobody sees the tops of buildings in cities, even though we spend billions of dollars on them. When you are selling an architectural model, you can look at the top of the building and say: “My goodness, that’s a great top” or: “You should change the top.” That might matter when you are viewing skylines from a distance but when we use cities we don’t see what’s going on past the third or fourth floor. The way we design doesn’t reflect anything along that line.”

They were done by planners who liked to draw a site plan and put a lot of green on it. They forgot about the grey matter that leads to an interesting life. — Richard Saul Wurman

Wurman’s criticism was not limited to Hudson Yards. He lamented the reaction to a 1952 proposal by his friend and mentor Louis Kahn, who sought to re-center Philadelphia’s urban grain squarely on humans and leave cars, literally, at the gate. "When Louis Kahn put those castles of parking garages around his fantasy Philadelphia, people laughed,” Wurman recalled. Likewise, he lamented the missed opportunity of the so-called ‘New Towns’ developed in the United Kingdom after the Second World War. “I thought they could have turned out terrific,” Wurman told me. “But they were done by planners who liked to draw a site plan and put a lot of green on it. They forgot about the grey matter that leads to an interesting life.”

This assessment won’t come as a surprise to readers. The practice of relegating the pedestrian experience below those of cars, corporate interests, or security infrastructure is one that has drawn the ire of urbanist literature for decades. Archinect’s editorial has previously published our own critique of the urbanist principles behind Hudson Yards, the streets of New York City, and the site of Expo 2020 Dubai. In Dubai’s case, I argued that the expo park’s design was a “warped exercise in utopian thinking” that “sacrifices the human scale in favor of imposing artificial monuments to technological and cultural prowess.”

In the same article, I argue that rather than using Expo 2020 as evidence of the flaws of utopian thinking, we should see this “dystopia in the desert” as an invitation to ponder alternative visions for future cities; an exercise which should embrace rather than dismiss utopian thinking. To some, Wurman’s vision of the ‘schoolhouse city’ is a utopia. In fact, Wurman himself used his 1976 AIA keynote to tell a story titled ‘What-If, Could-Be: An Historical Fable of the Future’ set in the ill-fated city of Could-Be, which promised that “public information must be public.”

Beyond Wurman, the history of utopian urbanism is rich with propositions that place the human experience at their core, whether William Morris’ News from Nowhere (1890) which dreamed of a future London grounded in human health, equality, and agency, or Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972) which used urbanism as a vehicle to reflect on human emotions and desires. When we imagine a utopian city, we do so first and foremost for the betterment of its citizens.

Our cities have an increasingly rich story to tell us about themselves and their citizens if we find new ways to listen.

That said, it is incorrect to label Wurman’s vision of the ‘schoolhouse city’ as a ‘utopia.’ By definition, a utopia is impossibly idealistic, with the word itself derived from the Greek “ou topos” meaning “no place.” By contrast, the technological developments of the late 20th and early 21st century mean Wurman’s vision has never been more attainable.

Today’s cities are a fusion of bits and atoms. Every day, the performance of our physical built environment is captured by millions of data sensors, from government networks to wearable electronics, measuring everything from air and light quality to pedestrian social habits. Our cities have an increasingly rich story to tell us about themselves and their citizens if we find new ways to listen.

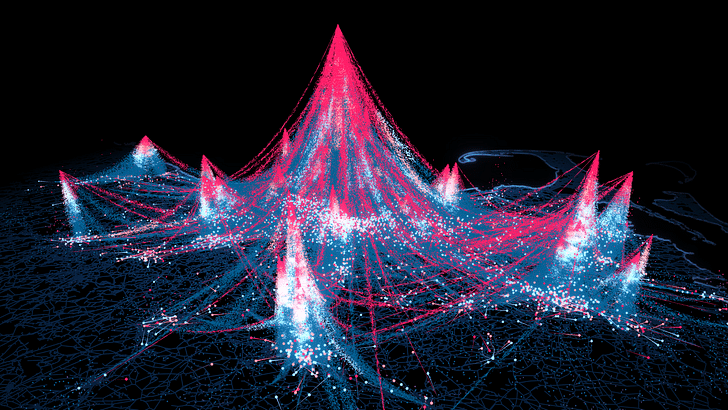

In recent times, few have done as much to articulate the promise of a ‘city of bits and atoms’ as Professor Carlo Ratti. The founder of CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati, director of the MIT Senseable City Lab, and curator of the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale, Ratti’s work across practice and academia is grounded in the impact of digital technologies on architecture and cities. For Ratti, the growing ubiquity of sensing technologies in cities presents new possibilities for citizens, policymakers, and designers alike to map their collective environment, a position he articulated most recently in the book Atlas of the Senseable City co-authored with Antoine Picon.

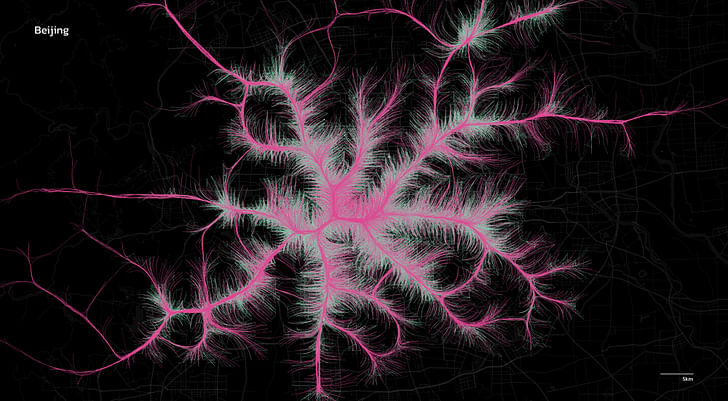

“With the introduction of sensing technologies, collective perceptions may reveal something deeper than the dizzying and sublime enjoyment of what Balzac called ‘the gastronomy of the eye.’” the book notes. “We now tend to consider the city from the perspective of billions of elementary occurrences recorded digitally, more and more often in real-time. It is as if the substance of the urban were made of billions of extremely small particles, moving dust, a cloud, or – even better – a massive swarm of pixels that allowed one to build a comprehensive picture of its inner workings.”

The outputs of Ratti’s Senseable City Lab have been well documented on Archinect. The group’s extensive library of map-based projects includes analyzing commuter habits across Chinese cities (The Potato Project), uncovering formulas for how people move across cities (Wanderlust), and creating interactive digital environments to understand Brazil’s favelas (Favelas 4D). Meanwhile, real-world experiments carried out by the group include deploying sensor-equipped bicycles across Amsterdam to understand theft patterns, an open-source 3D-printed environmental scanner, and Roboat, which saw autonomous boats launched into the canals of Amsterdam to encourage a future where autonomous watercraft could lessen the city’s car traffic. Meanwhile, CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati bridged the gap between landscape design and AI-controlled infrastructure with Helsinki Hot Heart, a project that decarbonizes the city’s municipal heating grid.

As architects, we should always play with whatever materials are at our disposal. — Carlo Ratti

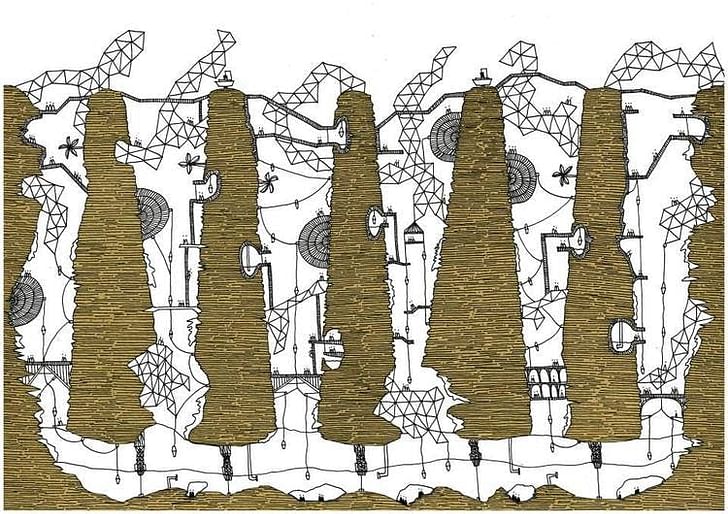

The lab's wide-ranging outputs are bound together by a method that the lab has dubbed ‘futurecraft,’ where future ‘what if’ scenarios are posited by the group and adopted as the setting for design proposals. As if through one of Wurman’s fables, these fictional though possible future scenarios offer Ratti’s lab the license to entertain consequences and possibilities which, when shared with today’s public, offer direction for conversation and debate on the future of cities.

“It is important to continuously play with technology to explore its potential,” Ratti told me in a recent conversation on the topic. “As architects, we should always play with whatever materials are at our disposal. Futurecraft is about using these materials and technologies to put forward an idea, and start analyzing the feedback loops that it generates.”

As Ratti notes in an earlier book on his group’s research, the Senseable City Lab’s approach has historical precedent, even within MIT. The acclaimed architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller, teaching at the institution in 1956, developed a framework titled 'Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science' which, in Buckminster Fuller’s words, “solves problems by introducing into the environment new artifacts, the availability of which will induce their spontaneous employment by humans and thus, coincidentally, cause humans to abandon their previous problem-producing behaviors and devices.” What has changed dramatically in the intervening 70 years, however, is the potential for groups such as the Senseable City Lab to leverage artificial intelligence as a tool for understanding the cities they are designing in, and for.

“There is a long lineage of research based on the visual analysis of cities which goes back to the origin of cities itself,” Ratti told me. “Traditionally, we expended massive effort in the collection and analysis of these images. However, the technological advances of the last decade have transformed both tasks. Thanks to open-source platforms from Google Street View to social media, we have collected more images and videos of cities than we could ever need. More powerful still, we can analyze them using artificial intelligence and, specifically, deep learning. We can train our systems to count trees, evaluate the urban tree canopy, estimate the age of buildings, and so on. As I wrote recently we can even use AI to estimate real estate values in different parts of the city. Deep learning models can interpret whether more businesses or cafes are opening, if streets are becoming cleaner, if homes are being improved, and predict future real estate values with striking accuracy.”

Despite operating in a field of research awash with autonomous systems, robotics, and artificial intelligence, Ratti’s outlook on the future of cities remains resolutely human-centric. While Wurman articulates the ‘city as a schoolhouse,’ Ratti posits a vision for the ‘city as a playground’ writing recently in The New York Times alongside Edward L. Glaeser:

“In a Playground City, mixed-use neighborhoods that tie life, labor, and leisure together generate what the New York urbanist Jane Jacobs calls the “sidewalk ballet,” a productive and playful dynamic in which a diversity of different users come and go at all hours.”

“Governments should empower citizens to participate directly in making the Playground City,” Ratti and Glaeser add. “The generation that grew up on social media has developed a fierce, collective yearning to come together in the real world, shown beautifully in the playful Facebook group New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens. We should harness this energy.”

At approximately a five-minute walk across campus from the MIT Senseable City Lab, the MIT Media Lab plays host to a new generation of designers who are already articulating, simulating, and prototyping visions for the future of cities, one which echoes Wurman and Ratti’s call to find intrigue and meaning at the intersection of bits and atoms. Naroa Coretti and Ainhoa Genua, two researchers from the MIT Media Lab’s City Science group led by Kent Larson, gave me an introduction to how they are developing technologies that understand and respond to human activity, and shaping strategies for living, working, and moving through future cities.

“As a whole, the group investigates how to create more efficient, sustainable, and vibrant future cities,” Coretti told me. “We have several strands in the group ranging from places for living and working to urban modeling to mobility, but they are all united by a vision for future cities; environments that are more walkable and of higher density. In the end, this interaction between people creates the vibrancy and potential for innovation. Within this vision, we are designing mobility modes, and engaging in this exciting synergy between urbanism and mobility.”

The MIT Media Lab is one of many research schools across the United States to interrogate issues surrounding the future of cities. However, in Coretti and Genua's description of how the Media Lab sees its role in this effort, one hears echoes of Wurman’s earlier description to me of how cities of the future should be shaped. “Today, everybody is too individual and temporal in what they do,” Wurman noted. “We instead need a long-term idea to work to, where each designer is operating their little piece of a wider group understanding, instead of just selling a building and moving on.”

Everything is subject to change, and this dynamic environment becomes an effective machine to generate ideas. — Naroa Coretti

For Coretti, one of the Media Lab’s strengths is its willingness to collectively adopt this wider group understanding; a group that extends beyond MIT to encompass an international network of cities, enabling the analysis of research implications across multiple cultures. “We are rather unique in that we have a clear opinion on how we believe the future of cities should be, though we are always open to changing that opinion,” Coretti continued. “We have ambition, but at the same time, we are not overly attached to our own individual ideas. There are so many ideas among the group that we are not afraid to close one project that doesn’t work and start another. Everything is subject to change, and this dynamic environment becomes an effective machine to generate ideas.”

In a demonstration of the Media Lab marrying a strong urbanist stance with a willingness to adapt and experiment, Genua unpacked her group’s work on micro-mobility, where initial research into the mechanics of autonomous bicycles led to a broader research project on the impact of autonomous bicycle fleets on cities.

“The City Science group had already prototyped various micro-mobility solutions such as the Persuasive Electric Vehicle and the MIT Autonomous Bicycle,” Genua explained. “We had the hardware, but the question was how would these perform as a fleet in a real city? Our original focus was on transporting people, but we realized that if you focus only on people, you have two high peaks of demand around rush hours, with little activity among the bikes for the rest of the day. Because of this, we began to look at how the bikes could transport goods as well as humans, which led us to food deliveries.”

These findings can then be passed to governments and city officials to offer them insights and shape decision making. — Ainhoa Genua

With little public data available on urban mobility pertaining to food delivery, Genua generated her own synthetic database, ultimately creating a multi-layer agent-based simulation model that allowed the group to understand how such a fleet would perform versus the current car-dominated network. Among the findings was an 80% drop in CO2 emissions when measured against both combustion and electric cars.

“Through these investigations, we start to generate insights into how a system such as micro-mobility or autonomous food deliveries could be implemented, what would work, what might not work, and so on,” Genua added. “These findings can then be passed to governments and city officials to offer them insights and shape decision making.”

From Wurman, Ratti, and the MIT Media Lab’s Coretti and Genua, we are presented with three perspectives on the future of cities. Within each, we hear a call to adventure, whether it be to learn in Wurman’s schoolhouse, play in Ratti’s playground, or create in Coretti and Genua's vibrant cocktail of human and non-human agents. While each of our three subjects arrives at different destinations, they do so from the same starting questions: How might people understand cities? How might people live, work, and move through them? How might people shape them? From New York to Dubai, our built environment is unfortunately littered with the consequences of designers, policymakers, and corporate interests not asking such human-centric questions.

Within each, we hear a call to adventure, whether it be to learn in Wurman’s schoolhouse, play in Ratti’s playground, or create in Coretti and Genua's vibrant cocktail of human and non-human agents.

The technological advances of the 21st century give new meaning to such questions. In this city of bits and atoms, perhaps we can find new avenues of adventure by asking cities what Louis Kahn asked of bricks:

“You say to brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’” Kahn told his students. “Brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ if you say to brick, ‘arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel over an opening. What do you think of that, brick?’ Brick says: ‘I like an arch.’”

Today, the city has become an organism in its own right, given its own character by the billions of daily interactions taking place across its landscape; interactions collected, mapped, and acted upon by an ever-advancing suite of non-human intelligent systems. If we reformulate Kahn’s question as ‘What do you want, city?’ we find that the city, as an aggregate of human and natural flows, can give us answers. As Ratti would argue, today’s city is ‘senseable.’

For Kahn himself, the city was a “place of availabilities,” where “a small boy, as he walks through it, may see something that will tell him what he wants to do his whole life.” As my conversation with Wurman drew to a close, one where overtures of his friend and mentor’s influence on architecture and urbanism were omnipresent, Wurman used Kahn’s description of the city as a place of availabilities to tell a final fable on cities and its people.

That is what we still are: a group of people with different interests and expertise that make things available for one another. — Richard Saul Wurman

“One of the fables in my UnderstandingUnderstanding book was of cave people sitting around a fire,” Wurman told me. “They are telling each other what they do, and what they like to do, which were sometimes not the same thing. It turns out one person knew the difference between poisonous and non-poisonous berries. Another knew how to raise kids in a way that they learn and explore. Another person talked about painting, another about making spears, another about using those spears to hunt animals without putting themselves in danger.”

“That right there is the beginning of a city. That is what we still are: a group of people with different interests and expertise that make things available for one another.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.