It has been almost ten years since Archinect last spoke with Bjarke Ingels. Back then, the topic of conversation was BIG's 'Hot to Cold' exhibition at the National Building Museum. Today, after a decade that has included award-winning Manhattan skyscrapers, floating cities, a Netflix profile, and a Serpentine Pavilion, it's hard to know where to start.

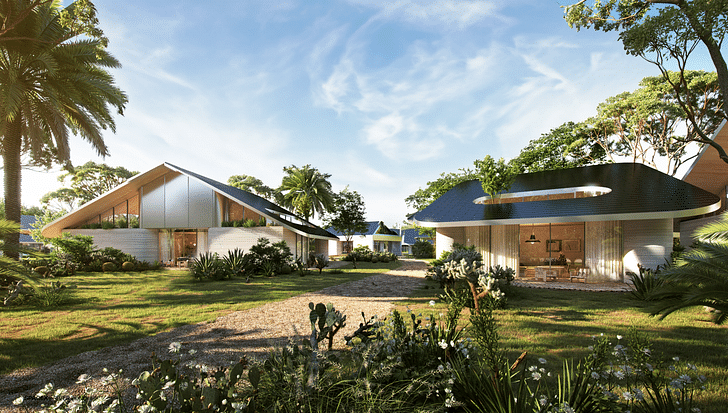

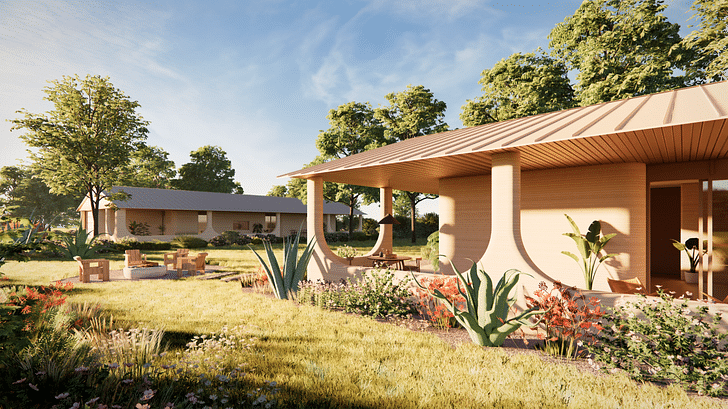

Among the most intriguing recent outputs of BIG's 700-strong team across the United States, Europe, and Asia, however, is their explorations in the field of 3D printing. In collaboration with construction technology specialists ICON, Ingels and his firm have overseen the design and delivery of a wide variety of 3D printed schemes, from a 100-home residential neighborhood and high-end hospitality project, both in Texas, to a Mars simulation habitat developed in collaboration with NASA. Now, in 2024, the team has embarked on its latest 3D printing endeavor: a selection of single-family houses, designed by BIG, to be included in ICON's new CODEX catalog of ready-to-print homes.

Last week, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Ingels as BIG was in the process of unveiling this newest chapter in their 3D printing explorations. In addition to discussing the specifics of BIG's designs for CODEX, we reflected on the wider future of 3D printing, the potential of alternative architectural business models, and the rise of artificial intelligence in the architectural process. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

Niall Patrick Walsh: We’re on the eve of BIG and ICON announcing its latest collaboration: a collection of pre-designed 3D printable homes for ICON’s CODEX catalog. As a broad question to start, what was your vision or philosophy behind BIG’s designs for CODEX?

Bjarke Ingels: In many ways, the catalog can trace its roots back to the beginning of our long collaboration with ICON, when we were investigating how single-family homes could take advantage of 3D printing technology. One of the homes we designed features a curving form where the roof structure is printed on the ground and then lifted up. It has the vibe of a Pier Luigi Nervi slab but takes advantage of the possibilities that come with 3D printing.

That home was a ‘one-off’ idea, but it led us to start talking about the possibility of designing a series of single-family homes at a more affordable price point. Eventually, it became the three collections that you see in the CODEX catalog. First, you have the Storm collection, which was designed with various features that are capable of withstanding hurricanes, catering to increasingly hurricane-prone regions. The Fire collection contains houses that are designed to be particularly resilient in places prone to wildfires. The last collection was the TexNext houses, which was essentially a series of typologies that have a long history in Texas, such as the shotgun typology and porch houses. These are forms that are uniquely Texan but are revisited and reimagined through the lens of 3D printing.

As you said, your collaboration with ICON has been a long one, and you’ve engaged with a variety of 3D printed typologies, such as the Mars Dune Alpha simulation habitat, a hospitality project with Liz Lambert, and the 100-home Wolf Ranch development. I can imagine each of these being steep learning curves as you experiment more with 3D printing. Were there lessons or experiences from those previous projects that helped shape your approach to designing for the CODEX collection?

They have all somehow been intertwined. The project at Wolf Ranch saw us populate a master plan with an architectural vocabulary specific to the 3D printing capabilities we had at the time. That process led us to talk about the theme of ‘making.’ In some ways, these conversations were the origin of CODEX. We reasoned that if you are going to create a community that will grow organically over the years, perhaps you don’t have to follow the traditional method where a single-family housing developer constructs an area with subdivisions, potential homeowners view demonstration houses that are all variants of the same design, and then each decide whether they want to purchase a plot and build one of those homes so as to move in months later.

This is what gave rise to the idea of CODEX: the possibility of creating a completely different way of organically delivering large-scale communities. — Bjarke Ingels

Instead, we noted that one of the true advantages of 3D printing is that you could actually have a handful of 3D printers based on the property, and every time someone decides to build a home, the 3D printer comes to life and delivers the home for you. Here, you could create a much wider variety of homes that could all be ready on demand. This is what gave rise to the idea of CODEX: the possibility of creating a completely different way of organically delivering large-scale communities.

From there, we could expand further. CODEX does not only have to be for a large-scale community; it could be made available to anyone who buys a single-family plot in any location. The owners can go to the catalog, browse through the various options, adjust their preferred style to meet the demands of their household, and execute it. In a sense, we are creating ‘home delivery on-demand,’ with an increased degree of customization, to a bigger audience. Of course, this is a great tool to have at a large-scale development like Wolf Ranch, but, in general, it can also offer a new way of buying a home in any developing area.

This wide variety of 3D printed collaborations also means you have experimented with construction-scale 3D printing more than most. To many architects, this is all still a new or unexplored technology.

I’m curious about whether you see specific circumstances in which 3D printing could be a preferred choice over conventional methods. For example, ICON themselves see large potential for 3D printing in the creation of habitats on the Moon and Mars, while I’ve spoken to other architects who see potential for 3D printing in emergency contexts, and if we are talking about form, for creating curving or undulating surfaces.

Actually, the new generation of 3D printers ICON is unveiling tomorrow has come, in many ways, as a byproduct of our work with NASA. You could say that the demand pressure for developing this new type of robotic arm printer came from the requirements of building on the Moon where you don’t have the same ability to lay out tracks for a gantry crane to run back and forth on an even surface, as you might have in some places on Earth. Rather, from a single point, you can print without all of the site preparations that come before the 3D printing process as it largely stands today. The new generation of printers can, therefore, print much taller and more complex structures in a more complex environment, essentially increasing the quality and speed while lowering the cost. This is one of the most interesting parts, for me. Technologies that are developed for the difficulty of building on the Moon and Mars actually end up necessitating innovations that are useful here on Earth.

Technologies that are developed for the difficulty of building on the Moon and Mars actually end up necessitating innovations that are useful here on Earth. — Bjarke Ingels

That said, in the immediate future here on Earth, low-rise structures are still best placed to take advantage of 3D printing as the technology stands right now. And, of course, in any environment where you have limited access to the production apparatus of architecture, 3D printing can be an advantage because of the on-demand nature of the technology. Single-family homes are still a huge category where there is an obvious ability to deploy 3D printing quickly. With that typology, the effortless customization and freedom of capability in 3D printing could potentially be a massive improvement compared to what is possible using conventional construction.

You mentioned earlier about how CODEX offers homeowners a new purchasing model. You could also say that it offers architects a new business model. We are a profession that traditionally allocates a given piece of time to a single client, billed by the hour or as a percentage fee. With CODEX’s catalog approach, however, you start to see a different architect/client relationship, where architects could be working for hundreds of people at a time, both now and in the future. Architecture starts to shift from a service to a product. That’s just one example; you’ve also engaged with other delivery models, such as Nabr.

How large a part do you see these alternative models playing in the future of the profession? Do you think, as some economists argue, that the traditional way we offer professional services is rather outdated and has room to evolve in the 21st century?

Both can exist. The electric car has not spelled the end of the combustion engine. The airplane was not the end of the train; on the contrary, right? However, the product business model is still interesting. It offers the manufacturer the ability to refine, improve, and enhance their product as they deploy further iterations. As the product matures, they will start to receive feedback, and the experience of building the first or second house will cause them to iron out issues that will improve the quality or effective delivery of the third or fourth house. Similarly, for architects, the idea of designing and maintaining a product line means you might still be working on it, improving it, and enhancing it as an ongoing process rather than starting from scratch with every commission.

For architects, it could be useful to have that opportunity where, once they retire, the energy and intellectual property they put out into the world could still be working for them for decades to come. — Bjarke Ingels

There is another interesting aspect of the product approach. Back in 2009, I cofounded a product-orientated design practice named KiBiSi, and after maybe five years, we decided to put the practice on hold because we all had other commitments. But we still get together every year for a good lunch to decide what to do with the royalties that keep ticking in even though we have not launched new products lately. For architects, it could be useful to have that opportunity where, once they retire, the energy and intellectual property they put out into the world could still be working for them for decades to come.

Then, of course, the arrival of artificial intelligence onto the world scene has become another interesting extension of our professional landscape. Sam Altman has a bet going in his circle about what year we will see the first one-person company worth $1 billion. In that scenario, you may have a single individual amplified with the power of increasingly capable artificial intelligence who is able to source, invent, market, and deliver increasingly large ideas. You can also imagine that being a logical next step for CODEX: the application of AI.

Speaking of artificial intelligence, another major announcement coming from ICON tomorrow is Vitruvius, which the company has dubbed an ‘AI Architect.’ As you mention, the last two years, in particular, have seen a massive proliferation of AI as a tool for the design and delivery of architecture. How do you see AI integrating with architectural practice in the near future, and do you have a vision for the future relationship between human and non-human designers?

Right now, we are mostly using AI for well-defined tasks and to optimize or apply finishing touches to existing workflows, but we can look at the bigger picture. I was drawn to architecture because I loved drawing with crayons and brushes. When I started architecture school, I had to learn how to draw with straight-edge rulers. Of course, I loved the sensitivity and freedom I had with crayons and watercolors, but through rulers, I gained the ability to draw multi-point perspectives and isometric drawings; I lost some control but gained a new world of opportunities. Then I had to learn to draw with a mouse. I loved the feeling and tactility of a physical drawing using rulers, but the mouse allowed me to create complex 3D models, apply textures, play with daylight settings, and move around in three-dimensional environments. Again, I lost some of the control I was used to but gained a whole new world of possibilities.

AI eliminates the barrier of entry for delivering incredibly complex visions. — Bjarke Ingels

Today, you could say that I have graduated further to draw with people; intelligent humans. I work with around 700 architects, all of whom are incredibly smart, brilliant, thoughtful, creative, well-educated human beings. You could say that I don’t have the control I once had holding the crayon myself, but I gained a whole new world of possibilities by interacting with people, having conversations, making suggestions, and swapping sketches back and forth. You could say that I am drawing with human intelligence to arrive at our visions.

In that sense, I believe that a young designer today, whether they are just entering architecture school or have just graduated as an architect, can use AI to leverage the same creative force as someone like myself who spent a quarter of a century building a team of 700 smart people. This person fresh out of school can wield a similar force by thoughtfully and carefully curating AI prompts and outputs. AI eliminates the barrier of entry for delivering incredibly complex visions. Just as importantly, these visions and productions can be delivered with great skill and precision. It is similar to today’s digital video and camera technology, which means that one person with a good iPhone and laptop can deliver what, just a few years ago, may have needed a whole film crew. The barrier to entry is evaporating, and anyone with the talent and vision will be able to achieve outputs that otherwise would have been reserved for large design houses such as my own.

Before we wrap up, do you have any final thoughts on your mind on 3D printing and AI?

Perhaps one last thing that is important for people to understand: I was watching the Oscars yesterday, and Christopher Nolan, who finally won a well-deserved Best Director Oscar, used his speech to remind us that cinema and film are only one hundred years old. Compared to other art forms like sculpture and painting, cinema is a baby. Nolan was grateful that the academy saw him as someone who had contributed meaningfully to what he considered to be the early stages of a new art form.

What we are experiencing today, even though it is becoming increasingly impressive, is still just the humble beginnings. — Bjarke Ingels

We have to remember that 3D printing, in general, is relatively new. 3D printing in construction is even newer, less than a decade old. However, the pace of improvement is staggering. What we are experiencing today, even though it is becoming increasingly impressive, is still just the humble beginnings. The same can be said for AI architectural systems like Vitruvius. ChatGPT was launched two years ago and was unleashed for learning and testing not in a closed environment but to millions of people worldwide, and the speed of learning and increase in quality from then to now is staggering.

In that sense, Vitruvius represents the humble beginnings of architecture-focused AI, but once it gets to collaborate with all the intelligent humans out there, its learning curve is going to be extremely steep. I’m excited to see what is going to come out of it.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

35 Comments

"the possibility of creating a completely different way of organically delivering large-scale communities."

Why different? Why not the best way of delivering large-scale communities? This constant search for novelty might satisfy the ego, but I'm not sure it's the best way of delivering architecture the public will embrace.

I fear that the BIG aesthetic and material choices are too different to achieve widespread adoption in the US.

The first company that can 3d print this will make a gazillion dollars.

reallynotmyname, sadly I agree.

I don't think that house is a choice as much as the result of architects not knowing how to compose and then the trickle down effect to builders who must shmear some traditionalism on an efficient box in a suburban landscape.

How would you 'compose' then Thayer-D?

I would start by down playing the garage door, if moving it weren't an option, then tell you it's a completely novel approach to delivering suburban track homes.

I agree. How would you do this for a home with only street access on one side for a typical suburban lot measuring 70'-0" x 90'-0" ?.

With 18' side yard setbacks, you have more than enough width to accomodate a side yard entry or pull the garage back from the front elevatio. As for making the masses sing, plenty of historic examples to learn from, just start drawing and ask others what they think. The most carbon neutral solution would be to buy an old house and fix her up!

70' wide, 90' deep. Even with 5'-0" side yard setbacks it's going to be tough. That's assuming you want a back yard.

You need 24'x24' for a two car garage which leaves you 46' in width. Take out 10' and you have 36' in width, more than enough. Then place the face of the house 15' from the sidewalk and the garage doors 15' back from that. With a 24' deep garage, that gives you a 36' deep back yard and a 36'x39' house of 1404 sf per floor. Do a slab on grade and you've exceded the average house size, and that's with a 36' x 90' back yard, more than enough to kick the ball and room for a grill, but it still needs to work for the average person.

You can't hand pictures on curved walls and you can't easily alter, add, or subtrack with this kind of construction, at least not with some boys at Home Depot. And what's with the lack of windows behind the porch or the million dollar ones in the little court yard? People like light and views, especially if living in the prestine nature these renderings show. I'd also like a gutter and some positive drainage, especially in the tropical climate this flat site shows. Can I paint this any color and can I haz a screen porch? Does it come in a craftsman style or would that be kitch? No doubt, there's a future for 3-d printing, but squirting out a concrete house from a tube doesn't seem like the most practical, economical, or marketable solution, at least not in this form. Maybe prefab?

Most cities have 25' front yard setbacks, 10' rear yard setbacks, and a min of 5' side yard setbacks. The typical gross garage footprint is 26' x 28' (26' x 30' is ideal). This allows for maneuvering around the cars and some storage.

.

Here is 10 minute sketch showing a few options. It's mostly about the lot size and if an alley is available. The home below would be a comfortable one level, 3 bedroom 2 bath around 1,800 sf gross. Notice how small the rear yard is the average 70' x 90' lot if you set back the garage?

Looks right. The only things I see is are an oversized footpring and a garage that is maxed out and need to be connected to the house in this market. Given a tight lot, these dimensions would get harmonized with the exterior of the house, which is where an architect's skill in composition comes in.

The house footprint is shown as the max the will fit. The garage isn't oversized (by American standards). Also, the lot is the average size and setbacks for homes in America. In my opinion, pushing the garage back 20' isn't going to change the appearance of the home much. It's still going to be a garage with a house attached.

As I said before - it's all about the site.

Y'all sleeping on Canada...

Nidus3D completes North America's first 3D printed three-story building | News | Archinect

.

There are many ways to tackle a site. That's the point of composition, not just taking a rule of thumb and squeezing one out. I'm pro-choice so I guess its about the type of community one chooses to live in. https://www.thegazette.com/news/cedar-rapids-targeting-snout-houses/

There are many ways to tackle a site. As I've said it's all about the site. If you don't have a large enough one, or one with alley access then you tend to get garage with a house tacked on.

For most people it's about the community they can afford to live in.

Chad, we/I use 20’x20’ at footprint for two car garages. In California only two car parking is required for SFD’s and only one of them is required to be covered.

That's great Orhan. The average car is 14'-10" x 5'-10". The average truck is 17'-2" x 6'-2". A gross garage footprint of 20' x 20' seem way too small.

I also question the willingness of builders to actually pass along any savings they get from 3d printing along to the buyer. I think they figure out the going rate for stick built, peg the sale prices of 3d print homes to that, and pocket the difference.

This is 3d printed and currently for sale in suburban Austin TX:

for comparison: https://www.redfin.com/...

God this is cynical. I don't understand how one can do an interview on printed concrete homes without even mentioning carbon emissions and climate change.

Bjarke and ICON are contributing to the very hurricanes and wildfires that they propose to protect us from.

The final development announced by ICON was CarbonX, a “new low-carbon extrudable/printable concrete formula.” Set to be deployed in live projects from April 2024, the formula is described by ICON as “the lowest carbon residential construction method that can be deployed at scale.” - AI designer and multi-story 3D printer among ICON technologies unveiled at SXSW

The main goal behind CarbonX was to introduce a material with significantly less embodied carbon as compared with standard concrete but without comprising on performance. We have already developed a building material for printing called Lavacrete, which was used in Vulcan, and CarbonX has been developed to be as strong, if not stronger. When developing CarbonX, it was also important for us to design for deployment at scale so that we can realize projects at an industrial scale beyond the lab. Essentially, CarbonX is not just a research investigation but will be our material of choice for our construction project moving forward. - Melodie Yashar, from 3D Printing, Artificial Intelligence, and Space Habitats: A Conversation with ICON’s Melodie Yashar

I'm very aware of their press release - any reason it wasn't thought to be important enough part of the interview with the architect? Coming up with a low-carbon medium should be a precondition of any of these discussions, and it would mean a lot more if it was a demonstrated technology and not a speculative mix that isn't yet at proof of concept phase.

ICON is issuing press releases claiming a 25% reduction in carbon emissions based on modeled (not actual) LCA data using a mix which they haven't built a home with.

BTW, just to be clear, we completely agree with the environmental problems with concrete, and the suspicion that concrete alternatives will fully resolve the issue.

While the interview with Bjarke didn't get into CarbonX, Niall did specifically ask Melodie Yashar of ICON about CarbonX in his interview we published last week, with her response quoted above ^

The issue of decarbonization is not an issue we avoid at Archinect - here are some recent stories we've covered on the topic

This type of development is not sustainable when you are selling single family homes or suburban lifestyle on wildlife areas. It’s ridiculous to think intelligent people are going to believe these types of housing is good for our future.

What are the benchmarks on being sustainable when is sounds like a branding exercise? There are no solar panels on roof, no stormwater collection to maintain on site, the scale and size of the home should be considered, and the amount of food/product resources being transported and the kind of waste it creates. It seems they are creating a new infrastructure in nature that might go against it.

AI technology can be only consider be a tool in producing prototypes a complex world but the architect with its life experiences can deliver a narrative of a building or site that builds identity and culture that can not be generated by AI. Individual creativity and understanding of a site is important. There should be a different types of housing community that doesn’t take too much land. Look at the past mistakes.

Yes, the waste of quality agricultural land in the US by way of it being turned into suburban housing is ridiculous. That this occurs when there are huge numbers of vacant homes and other structures in 2nd and 3rd tier US cities and small towns is also ridiculous.

Not to mention the fact that "sustainable single family homes" is a total oxymoron to begin with.

I couldn't agree more. True sustainability is more than the latest technological advance, and will have to tread lightly on nature, not be a cool version of suburban sprawl. Plus, I hope the concrete interior walls have a smooth surface or else it will just be elegant brutalism.

No, majority of interior walls are bumpy concrete with paint finish.

Note in your photo the pictures are hung on some kind of flat panel by the counter. Hanging pictures on the corrugated surface looks tricky, maybe undesirable. Rehanging and patching will be a nightmare. It looks like the cabinets abut this surface—and will let dirt in a space that is unaccessible. I can't tell how they manage light switches and wall sockets. And will dust settle on the corrugated grooves and be a hassle to clean? Then if you have an accident and have to patch. . . . What on earth is the advantage?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.