Liam Young was once described by the BBC as “the man designing our future.” In 2023, with open letters penned on the risks of extinction posed by artificial intelligence, such a role should be in high demand.

Young’s speculations on the future take the form of fictional stories that join the dots between culture and technology; a skill which he believes should sit at the core of the architecture profession. Amid the media frenzy on generative AI tools such as Midjourney and ChatGPT, Young stresses the vital need for a creative discipline that measures the dangers of AI against those of climate change: a crisis which Young sees as more dangerous both for its scale and deceptive ubiquity.

In June 2023, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Young about his career across design and media, as well as his views on artificial intelligence, climate change, and the role of the architect in addressing both topics. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: To begin, could you give an introduction to your various roles across design, media, and education as they stand in 2023?

Liam Young: I trained as an architect in Australia, though today I tell stories instead of designing buildings. I tell fictional stories about the global, urban, and architectural implications of new technologies. Fiction is an extraordinary common language in how cultures share and disseminate ideas, and if we as architects and designers truly value the ideas we put out into the world, it is our responsibility to find forms for those ideas to connect to an audience in evocative and powerful ways.

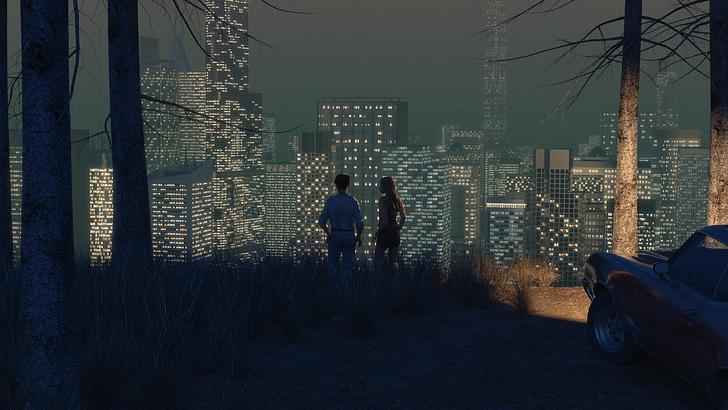

We are all literate in stories: from childhood, we fall asleep to stories or in the pages of a novel, while on Friday nights we find ourselves in front of a TV or flickering movie screen. Stories can become vessels for ideas in a way that architectural drawings sometimes are not. That’s part of why I am here in Los Angeles: making my own work, telling my own stories, building worlds, and designing for the entertainment industry. I treat stories and pop culture with the same rigor that an architect might treat a project, encoding stories with critical ideas about how technology is changing our lives.

Stories are products of culture, but they can also produce culture. As we write stories, we begin to write the world. At this moment, when technology is asking us to question the very foundations upon which we understand the world, I am creating stories that help us to make sense of this moment and to prototype possible ways forward.

The last time we spoke, you used the term ‘speculative architect’ to describe your career, which I thought captured beautifully this duality of both the storyteller and designer. Is that still a term you would use today?

Yes, I use ‘speculative architect’ because I still think that architecture is at the core of my work. Architecture is the craft of telling stories with and through space, and I see myself as an architect of imaginary worlds instead of buildings. ‘Speculative architect’ seems to be the term that communicates this best. At the same time, I don’t want to pretend that I’m the pioneer of this idea that an architect can speculate. Architects have always been speculators. There are times in history when engaging with imaginary architecture to prototype critical ideas was as valuable as placing a building on a real estate plot. I would argue that today is just such a moment. Technology is bringing so many things about our world into question. We are in a time that is being defined by what I describe as ‘before culture technologies,’ which is to say that the technologies we are talking about now have arrived faster than our capacity to culturally and sociologically understand what they might mean. This is a moment when speculation is a useful tool for getting ahead of this technology transfer chain and figuring out what type of technologies we should be investing in, what type we should be running away from, and what type should be responsibly regulated.

Telling stories is my way of getting ahead, and being in the room when these technologies are being conceived and prototyped. — Liam Young

Too often, architects are at the wrong end of that technology transfer chain, in that many of the advances being discussed in architecture studios have already arrived. Over the past five years, you could walk into any architecture school and find a studio group speculating on how driverless cars will change cities. But this reckoning was already happening among car manufacturers over ten years ago when they began investing billions of dollars in the technology. If architecture studios today discover that the technology is a bad idea, it’s not as if the tech sector is going to say “sorry, guys” and backtrack, writing off billions of dollars in the process. The driverless cars are coming whether we like it or not. My point is that architects should have been in those rooms a decade ago at those early stages of investment, and should have been part of envisioning what those systems might mean. Telling stories is my way of getting ahead, and being in the room when these technologies are being conceived and prototyped.

When we talk about speculation, especially in financial and real estate terms, we often see it as analogous to taking a risk. But I think we are in a moment now where not speculating is the risk. In architecture, we are accustomed to seeing speculation as something to do on the margins in between waiting for the phone to ring and for a client to commission a real project. But now, I think speculation is firmly at the center of our discipline. It is what many architects are and should be doing.

What do you think of the new capabilities we are seeing in AI today? One year ago, the technological fixation was the Metaverse; there were suggestions that the future of the profession was in metaverse architecture on virtual property plots. Today, fixations on the Metaverse seem to have died down, replaced by fixations on machine learning, generative AI, LLMs, etc. Even though people had strong opinions on the Metaverse, it didn’t prompt open letters by leading tech figures like we see today. What are your thoughts on these new popularized advances we are seeing?

I think the Metaverse was a branding exercise in some respects. It became a useful way of describing the convergence of a whole series of new technologies that were reaching maturity at the same time. It captured virtual reality which was having a moment in the context of the pandemic. It captured machine vision recognition which was developing with a sufficient resolution to map and understand complex environments in real-time. It also captured AI, which can govern and coordinate those systems alongside blockchain models that basically laid out the blueprints of what the economy of a digital world could look like. It was all loosely grouped into this thing called the Metaverse.

Ultimately, the PR machine behind the Metaverse resulted in a few fairly clumsy, embarrassing promo videos of a glorified version of VR chat with weird, bubble head avatars having Zoom meetings. But we were all sick of Zoom. We wanted to get away from our screens and get back into the real world after the pandemic. I don’t think the Metaverse has disappeared forever. It just doesn’t capture the same headlines that it did in the middle of the NFT hype.

The current fascination with AI in popular culture is in a similar moment where it is accessible enough for people without a technological background to crack it open and play with it for the ten minutes of patience they have, and then talk about it with their friends at dinner parties and stick it on their Instagram at the weekend. It is in a sweet spot where it is advanced enough to feed into our pop cultural ideas of what technology is supposed to do in the future and accessible enough that someone can dive into it and produce something magical.

We are at the peak of an AI hype cycle. — Liam Young

Do I think it is a signifier that our whole world is collapsing and that AI is about to rise up Terminator-style, take all our jobs, and throw the world into ruin? No. Instead, we are starting to see the very early ripples of how it could be a fundamental tool in our lives. I am sitting here right now looking at the Hollywood sign, in a town that is currently at a standstill because writers have gone on strike. The actors might soon join them [Editor's Note: this has happened between the time of the interview and publication, with the SAG-AFTRA strike starting on July 14, 2023]. The whole entertainment industry is shut down right now because people are striking in fear of their jobs, and in fear that AI is going to be deployed to displace all of the creators in the industry. It’s a seminal moment. It is like being on the Luddite picket line about to storm a textile mill. This is the first real-scale union action against AI. It is an undeniable moment. We are at the peak of an AI hype cycle.

The great irony is that we’ve historically been busy designing AI to perform mundane activities and allow us to engage in more creative jobs. AI was supposed to do the boring stuff we didn’t want to do, leaving us with time to compose symphonies and write novels. It just so happens that the most PR -friendly applications of AI right now are to make images and write stories.

Is it a big enough moment that it might propel you to use AI as a subject for speculating on the future, in the same way that you recently used climate change as the vehicle for your project Planet City?

The short answer is no. AI is a dangerous distraction from the pressing issues defining our generation. The world is on fire and we are worried about whether AI is going to write the first draft of our screenplays. The scale of climate catastrophe enveloping us right now is crazy. It is happening so slowly that we are relatively comfortable ignoring it, but that just makes it harder to spot. It doesn’t mean it is less important.

My body of work is born out of the present moment where climate change is no longer a technological problem but instead is a cultural and political problem. — Liam Young

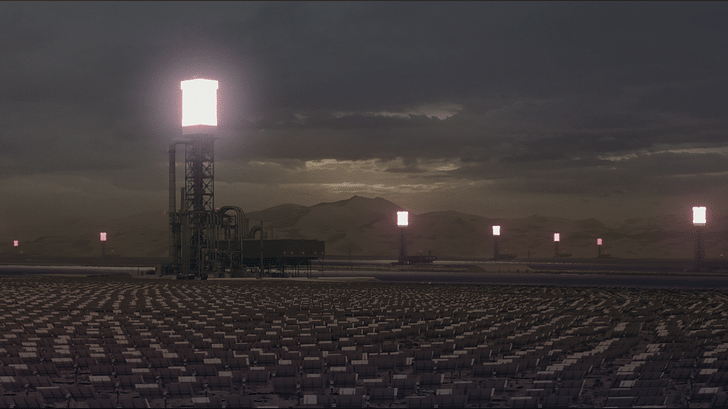

My current work is about creating new planetary imaginaries: new visions of a more productive and sustainable future. Maybe we can use AI to help us do that but AI is not the subject of our speculation by any means. My body of work is born out of the present moment where climate change is no longer a technological problem but instead is a cultural and political problem. Planet City is a working model of a hyperdense city which, unlike most sci-fi cities, is not built from any magical technology that doesn’t already exist. In this vision, we haven’t solved nuclear fusion or invented a magical lightweight building material. Everything that makes that city work is technologies that have already been tested and proven, and in many cases have been around at scale for 10 to 15 years.

If anything, the takeaway from Planet City is that we are not sitting around waiting for some billionaire to invent a new technology that will solve the crisis for us. We are not waiting for AI to mature and deliver us from climate change. Everything we need is already here. Climate change is now a crisis of imagination and culture, not technology.

When I say a ‘crisis of imagination’ I’m referring to the fact that many of our current visions for sustainable futures are based on failed environmental ideas from the 60s and 70s. It has us putting trees on rooftops and making community farms in Brooklyn. It has us driving electric cars and turning the heating down. It consists of really small-scale local community actions such as growing your own tomatoes and raising chickens in a log cabin somewhere. Maybe there was a chance in the 60s to make a difference through that scale of change, but we are so far beyond that point now.

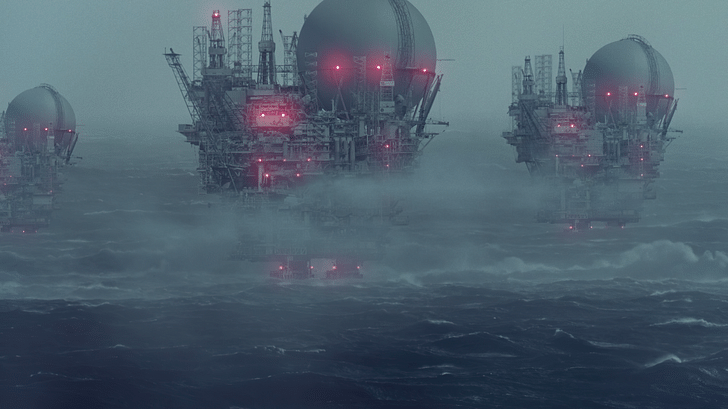

We need radical, systemic, planetary change, but in our popular cultural visions of the future, everything that operates at that scale is dystopian. It is the work of a Bond villain or a mega-corporation. What I am trying to do is manifest massive, systemic, planetary gestures. In Planet City, it is a cooperation and multi-generational migration, while in The Great Endeavour, it is through a multinational collaboration that will become the largest construction project in human history- the creation of a planetary network of carbon removal infrastructure.

I think there is a real danger that AI is being framed as either a solution or a dystopia, and it is neither. — Liam Young

These are the great challenges of our generation. AI is just a signpost along the way. It is a distraction, like slowing down to get a closer look at a car crash on the side of the road. We are on a much larger journey. I think there is a real danger that AI is being framed as either a solution or a dystopia, and it is neither. Technologies like these have always just been an exaggeration of ourselves, extensions of our own fears and anxieties, hopes and dreams, It is just a layer that has already been draped over our cities for years. It has only caught the imagination today because ChatGPT and Midjourney are more flashy that AI-based traffic management systems.

This reminds me of an open letter that was circulated in May 2023 which was signed by a range of high-profile tech figures. It said: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.” At the time, I was struck by the fact that the letter did not list climate change as a societal-scale risk alongside pandemics and nuclear wars. It goes to your point that the climate crisis does not evoke the same sense of societal urgency that AI has. Do you have thoughts on why that is?

I think it is because dealing with climate change is hard. At the moment, regulating AI involves getting five tech companies in a room and shutting them down. It is much more manageable and tangible. The existential threat of climate change is unwieldy and is happening at a pace that means you can forget about it as part of your daily life. That allows one to develop a narrative that suggests climate change isn’t real or isn’t going to happen. I am in a country that can’t even agree that climate change is a thing, let alone how to act on it. With AI, by contrast, we can all immediately see a writer or concept artist being put out of work. Evolutionary, we have evolved to deal with a short-term risk more than a long-term risk. The regulation and management of AI is also immediately more accessible to people. We can see a roadmap for what AI regulation might look like. But a pragmatic, reasonable, believable roadmap for dealing with the climate crisis is so far beyond what we’ve done to date that it just becomes displaced.

This is why we need to become much better at narrating these contemporary conditions in a way that allows us to deal with them in a meaningful way. Both AI and climate change are in desperate need of a rebrand. AI in particular needs a rebrand to quieten it down because, right now, it is neither artificial nor intelligent. The reason that Midjourney and ChatGPT have caught the public imagination is that the software programs are doing things that look like human creativity when in reality, they are large-scale pattern recognition and synthesis systems. However, they are doing so at such a large scale and speed that it disguises the mechanics of what is happening behind the scenes and looks almost like magic. We see it as intelligence in the way that we think of our own intelligence, and that is scaring us. If we rebranded it for what it is and called it ‘data sorting and analysis’, then it is no longer a headline.

We should be talking about a climate apocalypse in the same way that we would talk about a forest fire on our doorstep. — Liam Young

Similarly, climate change needs to be rebranded to be thought about in much more immediate terms, which we are starting to do when we call it a ‘climate crisis.’ We should be talking about a climate apocalypse in the same way that we would talk about a forest fire on our doorstep. The terminology and language around climate change have been constructed in the context of decades-long fossil fuel industry lobbying to make us think that climate is either our own personal responsibility or something that is not really a problem, like a climate shift that the planet is naturally happening regardless of human involvement. We are in a real crisis of narrative.

This brings us back to your initial point about the power of speculation. It is interesting to watch regulators, developers, CEOs, journalists, etc. all trying and failing to articulate a coherent, nuanced future for AI. It always reverts back to fear. Sometimes it is actually the creative disciplines, whether that is comedy, art, film, etc. which can be more powerful at capturing our attention or imagination on the future. You said earlier, and many times in the past, that architects are in a strong position to use their learned skills for more than real estate development, and that we can join dots in the climate crisis that span the political, cultural, mechanical, biological, etc.

Architects are really uniquely positioned to operate in this moment. We sit at this interesting intersection between culture and technology. When we go through architecture school, we take classes in philosophy and history as well as engineering and computer software. There are very few disciplines left that straddle that line. Throughout this whole conversation, we have been talking about how you cannot separate technology from culture. The way that AI lands is a cultural issue. I have been trying to do the same with climate change and make it a social and political issue. If we move on from the traditional role of the architect as being makers and shapers of physical buildings and start to think of the architect as someone who explores the changing nature and possibilities of ‘space’ in all its forms, both physical and digital then I think we can discover a much more expanded field in which we can add value.

Architects are really uniquely positioned to operate in this moment. — Liam Young

That said, there certainly is also a role for architects in the context of AI. I previously made a film titled Seoul City Machine, which was one of the first films written in collaboration with an AI that we trained on urban management protocols. This was our way of thinking about how we might interface with future cities at a time when the early DNA of how we interact with AI was being manifested in chatbots like Siri and Cortana. What does it mean to have a conversation with a city managed by AI?

Now, we are about to launch a film called Choreographic Camouflage, where we worked with choreographer Jacob Jonas to develop a new vocabulary of movement that would disguise the proportion of the body needed by body detection algorithms to surveil and identify people, like how facial recognition software failed to recognize people in masks during the pandemic. When technologies such as machine vision, recognition systems, and LiDAR scanners replace human eyes as the dominant apparatus for looking at and understanding the world, what does that mean for us as designers?

In my book Machine Landscapes, I argued that architects should become more involved in the design of architectures inhabited entirely by AI and technology such as data centers. As part of the book, I spoke with Deborah Harrison, who was one of the early personality architects for Microsoft’s Cortana. She talked about some of the seismic decisions they made: Should Cortana be male or female? What accent should it have? Should it be submissive or sassy? Aggressive or docile? These are massive design decisions taken in the context of AI. I believe there is a role for architects in that.

At the same time, we need to think about what it means to transition from fossil fuels and to weave energy and food production into our lives. We need to do so in a way that counteracts the center-periphery dichotomy where too much of our waste systems operate out of sight and out of mind. We are eating up the resources of our planet in a way that is totally unsustainable, and architects should be participating in conversations about how to address this.

I believe that the traditional discipline of the architect working in an office making buildings is no longer the core of the profession. — Liam Young

None of these problems are to be solved with a building. We desperately need to redefine what we do as a profession, including acknowledging what architects really do today. I believe that the traditional discipline of the architect working in an office making buildings is no longer the core of the profession. I think this is actually the margins of practice, and that those who have discovered new business models and new economies of practice are the new players. So, I don’t think I am arguing for something that isn’t happening already. I’m just trying to draw our attention to it and get the rest of us to both celebrate and meaningfully support it.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

1 Comment

This is such an amazing interview and Liam you are doing such poignant and difficult work! Gait detection terrifies me; it’s part of why I love wide-legged pants and big gauzy shirts; I want to hide myself in their flow.

Change on a wide scale is what is needed.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.