Ever since her childhood summers sewing patterns at the family dining table, Felecia Davis has understood the power of textiles to be a vehicle for communication, connection, and understanding. As her career in architecture unfolded in parallel with wider advances in computational capabilities, Davis dedicated her studies, and subsequent career, to the question of how computational textiles could intersect with and challenge social, cultural, and political constructions.

This dedication to mobilizing design and creativity in the name of confronting societal biases permeates Davis' many leadership positions, whether as the founder of Felecia Davis Studio, a co-founder of the Black Reconstruction Collective, or as an associate professor at Penn State University, where she directs SOFTLAB; a research group dedicated to tools, methods, and design solutions associated with computational textiles. Davis’ leadership in the field has been recognized through many honors, including the Architectural League of New York’s 2022 Emerging Voices award and Cooper Hewitt’s 2022 National Design Award in Digital Design, while her new book, Softbuilt: Computational Textile Architectures, is due to be published in October 2023.

In June 2023, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Davis about her career as a practitioner and educator. We explore how Davis’ interests in computation and textiles emerged, how the two interests manifest in her work today, and how her lab’s ‘soft system’ joins wider efforts to confront biases, discrimination, and disempowerment in both artificial intelligence and society at large.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: Could we begin with an introduction to your various roles across design and education?

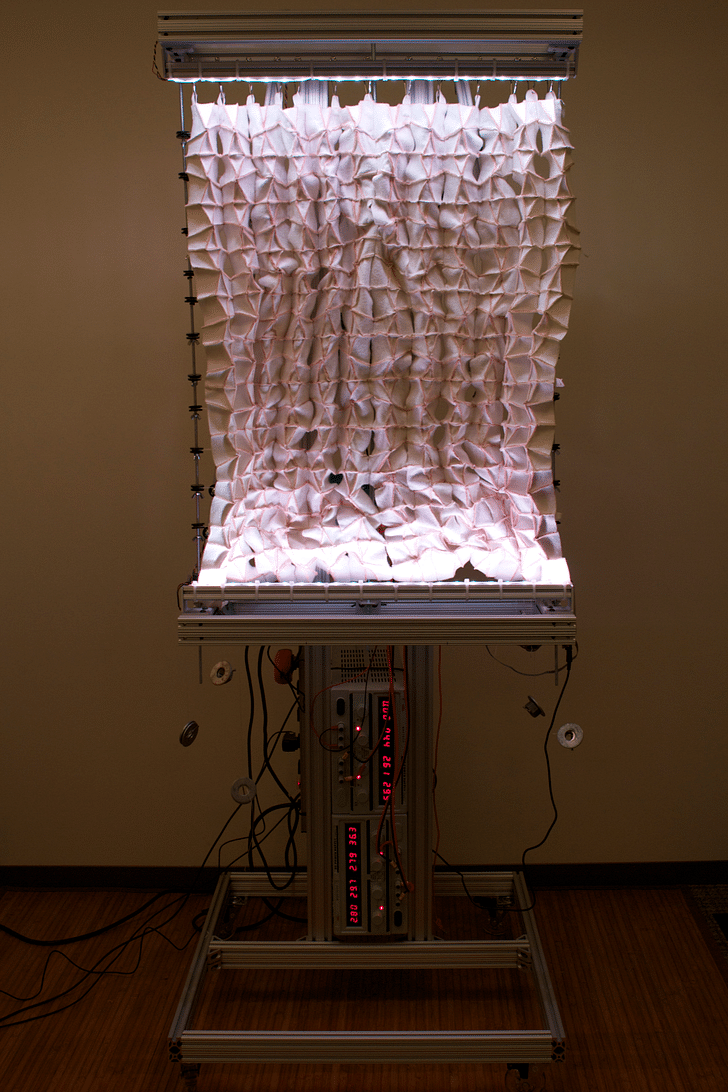

Felecia Davis: In the education space, I’m an associate professor at Pennsylvania State University. At Penn State, I direct SOFTLAB, which is a lab dedicated to tools, methods, and designs associated with computational textiles, which are textiles that either have electronics embedded in them or use the natural properties of the fabric itself to communicate information to people. In a single line, we are interested in the idea of communicating through textiles at several scales, including the architectural scale. Beyond SOFTLAB, I have my own studio, Felecia Davis Studio, where I take on commissions for particular design projects or artwork.

We are interested in the idea of communicating through textiles at several scales, including the architectural scale. — Felecia Davis

There are certainly overlaps between SOFTLAB and Felecia Davis Studio, but I would say that SOFTLAB is primarily research-driven. We support research work performed by Ph.D. students, MSc students, and undergraduates. The idea of training people to do research is important for us, ensuring students understand how to actually ask a research question, what methods they need to utilize, and what results they want to achieve. There is often an emphasis on scientific methods, though we also accept that in some cases, an artistic way of asking questions may be more important than the scientific in driving the project. When I then introduce Felecia Davis Studio into the equation, I usually describe my career as being in architecture, with an interest in how textiles shape and communicate with the environment at various scales. Someone might see our work and ask what relevance clothing has to architecture, but we must remember that when you embed electronic communication in clothing, it triangulates you to the space you are walking through. Textiles and architecture become interdependent here.

How did these three pillars of architecture, computation, and textiles emerge in your life to become core components of your work today?

It certainly isn’t a linear story, but when I reflect back on my journey, I can start to understand where these interests emerged. When I was very little, my family had gatherings where we would place sewing machines on the dining room table and make clothing out of patterns we had bought and modified. My aunt was heavily engaged in fashion design; it was a dream of hers. She never practiced it professionally, but it was certainly her passion. She was excellent at teaching us how to create different fashion techniques and sew our own clothes, which was important for me because local department stores never had colors or styles I was interested in. Sewing one’s own clothes was important for us as a vehicle for simply talking about our family. It was a time to catch up.

Fast forward to my architectural education, and I noticed that nobody was talking about soft materials. I knew from my childhood that textiles and soft materials were highly accessible to learn, but it was missing from my architectural space. It made me question my architectural training: Why were we only hearing about Frei Otto when there were so many other designers out there working with soft materials? This was absolutely the beginning of one strand of exploration for me.

I knew from my childhood that textiles and soft materials were highly accessible to learn, but it was missing from my architectural space. — Felecia Davis

The next important moment occurred when I was concluding my MArch, and students were given more agency on their topic of investigation. I took that as an opportunity to explore African textiles, iconography, and traditions. I saw an opportunity to use folding and textile techniques in an architectural context but was frustrated by the lack of tools available to help me figure out the structure. Today, we have a variety of capable tools that allow us to fabricate structures we could never have dreamed of when I was a student. This frustration stayed with me for quite some time until I was teaching at Cornell and started to see the technological landscape change. From there, I embarked on a Ph.D., which investigated how technology and computation could allow us to work with textiles with new structural systems, rather than relying on the established systems of columns, steel beams, and plates of glass.

This brings us to the present day. You’ve already mentioned that there are overlaps between SOFTLAB and Felecia Davis Studio, and it would be interesting to hear more about how you see the relationship between academia and practice in your work. Do they play off each other?

Yes, they definitely feed off each other. My professional work is often informed by the research questions I ask in my academic work and allows me to understand how such questions meet the real world. Engaging with practice allows me to ask: What happens when we let these ideas and concepts out into the world for people to interact with? What do they become? What are the results? In the opposite direction, I believe SOFTLAB allows me to think about practical questions, and to frame them in a way that may not be the AIA standard method of architectural practice. Overall, being able to go back and forth between these two worlds is important for my work.

Zooming into SOFTLAB, I’m curious about the lab’s disciplinary makeup. Do you mostly attract people from architectural and textile backgrounds who are interested in exploring computation, or do you see more students from computer science backgrounds seeking creative applications in their field? Or is it both?

I would say it is a mix. We have people that enter from architectural backgrounds with adequate mathematical training to start their Ph.D., who also engage with programming and machine learning courses. On the other hand, we have people from computer science who are interested in working more through an artistic medium. The common language that we impress on both backgrounds is that we engage with materiality and the tactile. I recall one student whose background was in virtual and augmented reality, and while I’m interested in that personally, the goal of the lab is to engage in the tangible, the inhabitable, and materials you can see and touch. The student actually ended up creating a method for working with tension structures which gave people a better intuition of how fabrics behave. I would also say that even though Ph.D. candidates often do not have to show a portfolio, we look for a base of design in order to see if people are interested in creative thinking.

Looking at the work you do at SOFTLAB, it is interesting how computation manifests in several ways. In one sense, you use computation as part of the design process, such as in Black Flower Antenna, where you developed an algorithm to predict the resting state of fabrics. But then, for other projects such as Textile Mirror, computation was part of the product itself in the form of sensors embedded in the fabric.

Indeed, we purposely use computation in many different ways, as well as at different scales. Sometimes it might be in a method such as the Black Flower Antenna. A Ph.D. student of mine developed an algorithm that allowed us to predict the resting state of a fabric with a defined shape and stitch; something which is notoriously difficult to model. We have now taught three studios over three years using her algorithm, so it has been well-tested. That is an example of what I would call the methodological use of computation in our lab. The other way, as you say, is to literally embed computational elements in the product itself. An example of this was the Quantified Walk project, where we teamed up with an industrial engineering lab to create a pair of leggings that used a machine learning algorithm to read the pattern of someone’s walk and sense their hip and knee angles.

For us, computation can also be considered as the way human beings approach construction. — Felecia Davis

We have also been thinking of computation in a more expanded sense. For us, computation can also be considered as the way human beings approach construction. How does nature construct? How do humans, as an extension of nature, construct? We see these questions as part of our computational approach in addition to tools and products.

The development of computational textiles is interesting in and of itself, but I have also heard you speak about connecting this work to broader issues. In a presentation last year, you outlined the idea of a ‘soft system’ which you described as a “technological system that can register design in relation to specific bodies and specific places, engaging in social, cultural, and political constructions.” Could we explore this idea of a ‘soft system’ more, and how you are using it to engage with social, cultural, and political issues?

It’s a central part of our mission. I try to teach students to acknowledge their position in the world, what class they are, where they came from, and to understand all of this in relation to what they are making. When we can understand the artifact we are making in the context of these questions, we can better connect with what other people might be experiencing. How might someone who isn’t from my own economic background connect with this artifact? Will they even have access to it? Positionality is an important part of our thought process; I encourage students to think about social constructions because they exist in every context our work touches. Where did the material to make this artifact come from? How was the computational code created? How do you structure the code so that the artifact behaves in a way that doesn’t exclude certain groups? It percolates through everything, and it can take years to learn.

I encourage students to think about social constructions because they exist in every context our work touches. — Felecia Davis

This is also the conversation swirling around artificial intelligence today. The databases that serve as the foundations for AI have not been carefully designed, and it's a difficult issue to solve. There are people creating methods to combat bias in datasets, but again, it goes back to positionality. If the developers of these datasets had more consciously understood their position in society as well as who they were, and if this was placed at the forefront of the database, we all might be more informed on the limitations or biases that may be found in AI. We can look to Joy Boulamwini as an example here, who showed how an AI facial recognition tool was not able to read her face because it was Black. If the people who gathered the database had asked who they were in relation to their research, the limitations of the database may have become more apparent. Now that Joy raised the issue, we are all aware of it and are looking out for it. But before these issues are uncovered by end users, it starts with the positionality of the designer; understanding how your own positionality can inscribe a bias or a boundary in your work.

Similar to Joy Boulamwini, you have also used your work and research to confront racial discrimination and disempowerment. You’ve previously identified how highways, redlining, and eminent domain were used as tools that reinforced racial discrimination. Do you fear that AI is and will continue to be the latest tool for propagating injustice, or are you hopeful that AI can be used as a tool to expose and confront biases? I often hear AI compared to a kitchen knife, which can be used to either cook a meal or attack someone, the message being that the tool itself isn’t inherently good or bad and that the human application of the tool is where the path is decided. I’m actually starting to question that metaphor. As you said earlier, many AI systems today are already preloaded with biases before being deployed in a way that the kitchen knife isn’t. We aren’t dealing with an objective system here.

Yes, it is important to be aware that AI is built on datasets that are already biased. It is a little different from the knife metaphor because, as you say, there are built-in biases in the original information that it is based on. We need to go back to the original information and change how those datasets were constructed. The context of this issue stems back to the 19th century, with crazy, scary experiments such as people’s skulls being measured to differentiate races from each other. This project of categorization and classification started hundreds of years ago and has become sublimated in the way we extract information. We need to look at this issue as a human condition. We either need to remove it entirely or recontextualize all the ways in which datasets are put together. There are people doing great work on this, such as Timnit Gebru, who lost her job at Google after pointing out the inequalities built into AI, and who has continued to actively warn against these dangers. I am hopeful we can do something about it, but there has to be willpower.

It would be fitting to end with a reflection on your own work as an example of articulating and confronting biases both in AI and society at large. You said the following in a recent discussion on your work at SOFTLAB, The Black Reconstruction Project, and Felecia Davis Studio: “Our work encompasses both our scientific look at figuring out computational tools and designs that we can use to make more soft architectures, and to use this kind of computational fabric to connect with people emotionally, to register their presence, and to provoke questions about the order in our society. We think about softness as a powerful quality to imagine reconstruction.” Can you expand on this quality of softness to imagine reconstruction?

I would say that in architecture, we use bricks, mortar, concrete, etc., and when I talk about softness, I am speaking to the practice of where these bricks come from, where the concrete comes from, and what that means for society. It is about looking beyond the basic materials and understanding how their context and creation shape society. In other words, this goes back to positionality: If you use water upstream, or dump concrete in it, what will it do for someone downstream? So when I talk about softness, it is looking at the interconnections, at conversations that need to take place, and practices that need to take into account their impact on a wider world.

Your environment and your position are vitally important to shaping ways of understanding. — Felecia Davis

When I talk about positionality, I am talking about relationships. That is what I mean by softness. Yes, there is the literal softness of the materials we work with, but interestingly when you work with literal softness, it can help you think about these relationships. The things we work with, whether objects or tools or products, all shape our brains. When you work with something that doesn’t necessarily have an immediate shape other than what you create, the act of making can change how you think about things. If you take clay, a block of wood, a fabric thread, or hay, you change pathways in your brain. Your environment and your position are vitally important to shaping ways of understanding.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

4 Comments

I am reminded of Anni Albers' weaving that so influenced aspects of Albert's work. Both, of course, being influenced by the tenets of Neo-Plasticism. Then the more subliminal / psycho-organic fabric sculpture of Lenore Tawney in the '60s and 70's I mention these artists in recognition of their work being conditioned by their surroundings and "fabric" of their time. No genuine artist is free from those overriding influences. except those who consciously engage a subject from a calculated standpoint that panders to an anticipated audience wherein the ideological sales tag is more important than their actual work integrity.

Every artist panders to their audience to some degree. It doesn't mean that their work lacks integrity.

What are you blathering on about, Van Nostrand?

It's a very biting post.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.