Assistant Professor of Sociology at University of Southern California, Veronica Terriquez received her Ph.D. in sociology from UCLA. Her research focuses on educational inequality, immigrant integration, and organized labor. Her work is linked to education justice and immigrant rights organizing efforts in California. Dr. Terriquez has also worked as a community organizer on school reform and other grassroots campaigns.

[This is the 2nd in a series of interviews with non-architects about subjects discussed in architecture. The 1st was with French scholar Mahalia Gayle on style, sexiness, and power.]

Mitch McEwen: How do you do your research?

Veronica Terriquez: Much of my research seeks to understand issues of social inequality and inform initiatives that aim to promote equity. In answering relevant empirical questions, I often partner with community groups that address some kind of social injustice. My actual empirical research tends to use original or published survey data to identify general patterns of social behavior, and in-depth interviews to obtain a deeper understanding of patterns I find in survey data. Occasionally I use GIS maps or participant observations in my work.

Here’s a concrete example. Several years ago, through the UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education and Access, I developed a research project in collaboration with SEIU (Service Employees International Union) local representing janitors and other low-wage workers. Many SEIU janitors were concerned that their children were not going to college, and they wanted to figure out a plan to improve educational opportunities for their children.

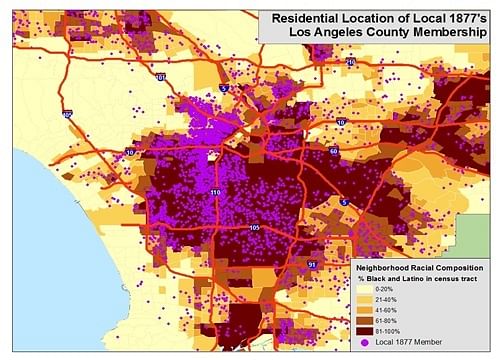

Photo courtesy of Veronica Terriquez

My colleagues and I set out to collect survey, interview, and other data in order to understand some of the educational challenges SEIU families were facing and the possibilities for supporting children’s academic achievement. We soon learned that union members were residentially concentrated in segregated Latino and African-American neighborhoods with under-resourced, low-performing schools.

Maps courtesy Veronica Terriquez

The research also demonstrated that many of the workers were applying what they learned through their workplace organizing experience to tackle the substandard learning opportunities found in their children’s schools. In an article I published in the American Sociological Review (2011), I drew on the data gathered from SEIU members to argue that labor mobilization can equip working-class individuals, including immigrants, with the capacity to become critically engaged in civic settings outside of work.

MM: What kind of relationships do you trace between locations and people?

VT: This is a complicated question without an easy answer. I think it’s important to consider how local history, immigration/emigration patterns, and urban design, interact with the relationships among civic organizations, government, and private enterprise. Local history of race and class relations, and current demographics to a great degree shape the dynamics among people in any location. As you and your audience know, the built environment, population density, and public transportation also matter. At the same time, civil society (including grassroots groups, artist collectives, professional associations, labor unions, religious organizations), local government, and local enterprise, and the nature of the relationship among these three spheres of social influence, play a significant role in how people live and interact within any given location.

So the local history, migration patterns, and the physical layout of LA and Detroit are very different—as are the relationships among different elements of civil society, the local government, and private enterprise. We therefore see very different relationships between people and place in these two U.S. cities.

MM: How do you see neighborhoods and neighborhood-level organizing now compared to the historic periods you reference (Civil Rights movement, 1990s labor)?

VT: I see a great deal of continuity. We are still learning from and adapting the grassroots organizing strategies that were used in the Civil Rights movement to address neighborhood and other issues in the contemporary period. At the most basic level, grassroots organizing entails the leadership development of individuals most affected by community problems. Ella Baker understood this and made it her focus to develop the leadership of students, women, and others involved in the struggle for Civil Rights. The activists of this earlier movement then mentored younger activists in the 1990s, including those involved in the immigrant rights movement, the revitalized segments of the labor movement, and other movements for social justice. The activists of the 1990s, to varying degrees, have also provided guidance to today’s younger generations.

One important break from the past, however, is the use of social media. Social media can be used to very quickly educate and mobilize a significant number of people to support a cause. A protest can be organized overnight. However, to really develop effective and sustained grassroots organizing, we still need basic leadership training and relationship building among stakeholders that often occurs through old-fashioned, in-person interaction, and popular education. Most grassroots campaigns to change institutions or policies cannot be won in a week or a month, but take years of hard work and require some level of continuity in leadership.

MM: One of the things that interests me about your work, as a Professor of Architecture and practitioner, is the radical potential of everyday places and what you call "everyday people." In the fields of architecture and urban design, the way we discuss radical potential can seem limited to luxury and its forms. The folks that you are interviewing and collaborating with do not seem nostalgic to me. Is this right? What kind of future world is being imagined or enacted?

VT: A lot of people that I work with imagine a world where all people, regardless of their social origins, can enjoy basic necessities, including access to healthy food and clean water, health care, a decent education, a living wage, and a safe and unpolluted place to live. People also imagine a world where they are not at risk of being deported, harassed by the police, or treated unfairly because they belong to a minority identity group.

What would these people have to say to those who are in the field of architecture? Many would probably want architects to engage in projects that broaden access to nice-looking public spaces, educational institutions, and affordable homes that use green design.

Posts are sporadic. Topics span architecture, urban design, planning, and tangents from these. I sometimes include excerpts of academic articles.

1 Comment

Nice interview, Mitch.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.