Sidewalk Labs, Snøhetta, Michael Green Architecture, and Heatherwick Studio have unveiled a controversial $1.3 billion plan to reprogram a portion of Toronto's industrial waterfront into a new smart city prototype that envisions a wireless, data-driven, and mass timber-filled future for the city.

The thorough and graphically-slick plan aims to articulate "a new approach for inclusive growth" by developing a 12-acre site with a mix of mid- and high-rise housing towers, shared pedestrian plazas, and commercial uses. The plan is being submitted for consideration by Waterfront Toronto, a government-funded corporation that is tasked with redeveloping the 1,977-acre Toronto Waterfront. The group selected Sidewalk Labs as a potential developer for a portion of the site in 2017. Since the initial proposal was unveiled, there has been a significant amount of public controversy over the project’s various approaches to data collection and continuous urban monitoring, and over Sidewalk Lab’s overall ambitions for the project.

The multi-faceted plan details specific approaches for economic development, urban policy, digital innovation, and building construction. Here’s a breakdown of some of the key design features for the building-focused portions of the proposal.

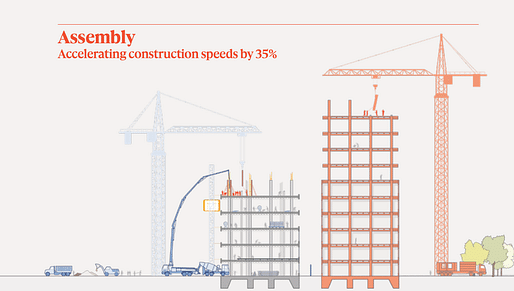

For one, factory-produced mass timber building elements will play a central role in the development, which envisions creating a “mixed-income community that builds on the city’s diversity” by bringing 6,800 new housing units to the site. The plan would ensure that up to 40% of the new housing units—roughly 1,000 apartments—are administered as affordable housing. The project team estimates that off-site mass timber construction can accelerate construction time by 35 percent while also reducing costs overall. The project would pioneer the use of certain construction and material approaches, including the application of so-called “shikkui plaster,” a fire-resistant finish surface made from egg shells and seaweed.

The scheme also features a mass timber “library of parts” system developed by Sidewalk Labs that has been interpreted by the architectural teams into a series of design proposals. Michael Green Architecture, for example, has created a residential scheme that assembles the various mass timber modules into a series of interconnected housing towers. Snøhetta, on the other hand, proposes to arrange the components in a semi-circular configuration around a central courtyard with the housing components lifted above the plaza on a series of stilts. With characteristic flare, Thomas Heatherwick Studio envisions a series of mid-rise wooden towers marked by projecting circular balconies and ground-level gothic arches.

In the plan, Sidewalk Labs articulates mass timber design specifications for different tower types, as well. Buildings 10 stories and under are to be constructed using Cross-Laminated Timber sheets only, an integrated, panelized approach that will allow fabricators to install interior finishes and most exterior cladding in-factory. The design will facilitate rapid construction and lower construction costs, according to the plan. Buildings rising between 10 and 20 stories will feature glulam post-and-beam construction with finishes installed mostly on-site, while towers rising up to 30 stories could be built using experimental construction methods currently being tested by the Sidewalk Labs designers.

The plan’s focus on speed of construction is geared toward one end: Money. Rapid construction, according to Sidewalk Labs, will allow the project to incur lower contingency costs, speed up the delivery of the housing units so developers can see a return faster, and perhaps create the conditions whereby “developers might even choose to accept lower rates of return on any given project,” based on the added benefits.

That might be wishful thinking, but other elements of the plan propose more level-headed urban approaches. Along the ground, for example, the structures are to be developed with an extra-tall first floor configuration. These “stoa” can be turned into different types of spaces, including loft apartments. The double-height spaces will be allowed a degree of programmatic flexibility as well, including in terms of enclosure, which can be partial or even optional along these areas. The arrangement could allow for indoor-outdoor civic and commercial plazas, live-work configurations, and modular retail concepts, according to the plan. The plan also includes a vision for designing “future-proof” parking facilities that can be converted to other uses “once self-driving vehicles arrive.” Designs for the concrete structures include locating parking ramps between floors discreetly on one side of the building for easy removal or adaptation in the future. The structure’s exit stairs, elevator cores, and mechanical systems, on the other hand, will be sized in anticipation of future conversion.

The specificity of the Sidewalk Labs plan goes down to the construction detail for certain building components. The factory-built, infrastructural quality of the district’s buildings allows for a certain amount of forethought to go into the design of various components, including, for example, along interior walls in the residential units. There, the designers have created customizable channels at the top and bottom of each length of wall panel where fire suppression systems, electrical, fiber optic, and other utilities can be located. The channels, concealed behind baseboards and crown molding, will embed future flexibility into the designs, the proposal argues, and allow for the buildings to accommodate changing technologies as they occur. A similar approach has been applied to the design of custom modular paving tiles that will fill the streets and plazas.

The plan also includes a continuous “real-time building code” monitoring system to ensure that every building remains up-to-date as codes change over time. The plan, anticipating privacy concerns from this arrangement, reads: “Designed with inputs from city government, Sidewalk Labs’ proposed building code system would monitor interior spaces in a non-invasive way for noise, air pollution, and other nuisance levels. The proposed system would be operated and managed by the building owner, and enforced by the City of Toronto, in full accordance with the standards established by the city.”

It is now up to Waterfront Toronto to consider the proposal, and, if approved, for city and other government entities to consider the project formally. A timeline for the full build-out of the project has not been unveiled.

For a full version of the plan, see the Sidewalk Labs website.

2 Comments

It looks like they crowdsourced every trendy McUrbanist idea, some good (wood, passivehaus) and some bad (wood everywhere, post-industrial parks). And yet it all seems like an empty Vegas-like facade, because they never answered the central questions: why? what is "urban tech"? how flexible is architecture, really? what is good design?

overall, it's hard to trust in big (tech) companies proposals because they didn't grow organically within the city. most likely they will run away once the city doesn't give them everything they want. Amazon, but with wood. If they were serious they would earn trust by building a single building first and growing organically rather than through top-down political power grabs.

Heatherwick and Snohetta are the perfect firms for this kind of work, capable of doing great design, but kowtowing to the image.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.