Exhibiting architecture is a notoriously difficult and contentious task. After all, how do you represent a spatial practice without neglecting the very qualities that made it worth representing in the first place? Nonetheless, it has a long history – extending at least as far back as the Enlightenment, according to the historian Barry Bergdoll.

Still, there’s likely never been a period with more exhibits, biennials, triennials than the last few decades. Just about every major city in the world, from Venice to Chicago, Oslo to Jakarta, now hosts some big architecture event. Beatrice Galilee, a trained architect and the newly-appointed curator of architecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has played a significant role in shaping and pushing the boundaries of this practice. In a talk delivered last night at SCI-Arc, she relayed some of the major – and often controversial – moves made over the course of her trajectory to becoming the first-ever architecture curator at the legendary museum.

Galilee began by projecting an image of the British collective Assemble, exuberantly congratulating them for becoming, just a few hours before, the first architecture practice to receive the coveted Turner Prize. The disciplinary breach represented by the awarding, and by their practice, represents well the sorts of architecture practices Galilee seems to favor. In the case of Assemble, it’s a sort of renegade refusal of the so-called givens of the profession – no waiting around for commissions, no crawling towards licensure. On the other hand, they are not caustic or adversarial; their rebellion – if it even qualifies as that – seems more pragmatic than adolescent. No wonder really, as Galilee herself has largely crafted her own model of practice as well, while still readily working with, and in, institutional contexts. When working with Icon magazine, at the nascence of her career, her goal was to “create a narrative of the practices we saw around us…not just reflect the news but also make it.”

In 2009, Galilee served as the European curator for the Shenzhen Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale, describing the former city as a “post-industrial place where culture started to regenerate the city.” Galilee showed an image of an entirely new-built landscape asking, “How do you present architecture in this context?” Her work involved soliciting projects that activated space, rather than represent existing built work. The “Go-West” project involved bringing taxi drivers from smaller cities in Western China (described as the sort of places that people in Shenzhen had never heard of), who would drive visitors around and describe their hometowns. The London-based firm aberrant architecture used the exhibition “as a way to invent a business,” crafting, through videos and displays, a how-to for developing an enterprise in Shenzhen. Another project, a small urban garden entitled “Landgrab,” served a double-function of growing food and diagrammatically representing food production in the city (ie. 40% devoted to a crop, representing the demographic that grows crops to feed urban dwellers). “The role of the architects in this biennial was quite expansive,” Galilee noted.

The same could be said of later endeavors. For the Gwangju Biennial in 2011, curated by Ai Wei Wei (he was imprisoned sometime during the show), Galilee was tasked with exhibiting “community,” a “sort of a nightmare task,” in her words. She commissioned the first full prototype of a “WikiHouse,” the open-source housing project created by Architecture 00, that has since grown into a sizeable project. Along with the Gopher Hole, a London gallery space located beneath a Mexican restaurant, projects included edible installations and imagined bridges from Europe to Africa.

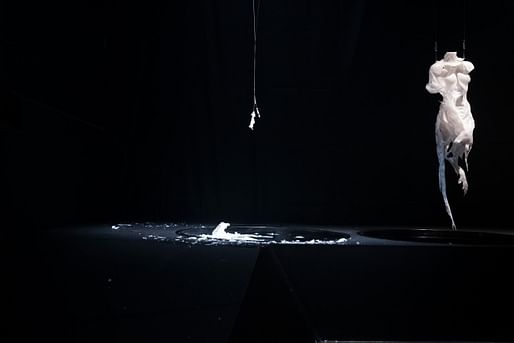

Galilee spent some time describing the 2013 Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Close, Closer, the biggest show she’s done to date. Working alongside other architects and curators, notably Liam Young, Galilee put together a wild medley of strange installations, such as a room that closed in on its occupants, a forest-like space filled with imaginary plants that could “cure” rabid wolves, a garment district “of the future,” in which dresses were made by dipping dancers in vats of warm wax. She readily admitted that the show received a fair amount of criticism; it excluded not just the old guard – Álvaro Siza Vieira and the like – but also traditional architecture in the brick and mortar, concrete and rebar sense. But it was also expansive and inclusive in it’s own way, soliciting a slew of “associated projects” from affinity institutions like the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York. “How do you explain the dispersion of architecture through these institutions?” Galilee asked, as the projected image displayed large the title of her talk, “the Institute Effect.”

Galilee concluded her talk, briefly touching on the first show she brought to the Met, a double-screened, digital display of Wolfgang Tillmans’ architectural photography, which had been shown previously at the Venice Biennale. She noted that her next project will be an installation by the artist Cornelia Parker on the museum’s rooftop, and then opened the floor to questions, which were dominated by the SCI-Arc faculty largely at the expense of their students. They tossed out a stream of poorly-veiled declarations of their own vested interests, configured into pseudo-questions through the academic equivalent of “up-speak.” Galilee responded patiently and well, despite the fact that the questions seemed to have little to do with her talk or her particular expertise: hasn’t the “social turn” in architecture neglected formal concerns and aesthetics, and therefore been bad for architecture? Well, Assemble, for instance… Why do you think American architects are so incapable of understanding the importance of social causes, creating only shallow, formal work? Well…

As I was leaving, frustrated by the faculty response, I considered the role that was implicitly projected on Galilee by their questioning. Namely, that the hidden mandate of this new(ish) figure, the architecture curator, is to confer their authority onto certain directions within architecture thinking, over and against others. But it would be difficult to construe the incongruous mass of strange and inventive work Galilee had shown as a singular unity. Rather, if anything, their unity is held only by a shared punctuation – and the most tenuous one at that – the question mark. Here, it is added not to disguise an assertion as a query, or to rebel for the sake of rebellion, but rather to push against limiting confines and unambiguous thinking. In turn, the role of Galilee, and those like her, should be to champion and elevate the uncertain and the incongruous – and those who advocate for it – in order to undiscipline the discipline and allow architecture to grow.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.