“There’s very little real architectural information that we get from a photograph,” the photographer Grant Mudford claimed during a panel last Friday hosted by Photo LA, an annual photographic exposition. In its 24th year at the REEF in the historic LA Mart building, Photo LA provides a space for both international and local galleries to showcase both contemporary and historic photography. The panel focused on the changing “human experience of space” of its host city, bringing together a variety of photographers, curators, and writers to consider the dynamic relationship between photography and architecture.

Mudford’s co-panelists seemed to largely agree with his assertion; they spent the hour primarily discussing the various difficulties lurking behind architectural photography. At the forefront of the conversation was the expression itself, as well as its sibling the “architectural photographer.” Without any hyphen to serve as tether, the two words in juxtaposition seem locked in a struggle for primacy.

Moderated by Barbara Bestor, architect and executive director of the Woodbury University Julius Shulman Institute, the panel also included Frances Anderton, producer of KCRW’s Design and Architecture; James Welling, artist and UCLA professor; Mimi Zeiger, critic and writer; and Gordon Baldwin, independent curator, writer and editor. Accompanied by a projection of his image of the Glass House, distorted using a colored photo filter, Welling discussed his unease with the term “architectural photographer,” which seems to relegate the latter role to the former object. He discussed how his work uses architecture as a “jumping off point” more than anything else. Through subtle (and less subtle) post-production manipulation, Welling works in collaboration with architecture rather than at its service. His work appears more oriented towards the creation of a beautiful arrangement of color and form than on an mimetic representation of a place.

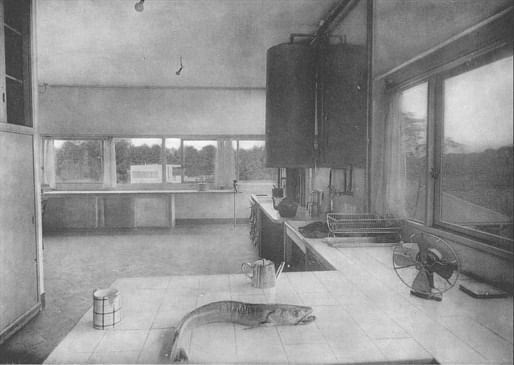

For Zeiger, who admittedly “deals in text” rather than image, architectural photography is used mostly at the service of her editorial projects. She displayed an image of the kitchen at Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein-de-Monzie. In the foreground, a dried fish was laid out on the corner, its body curved in pleasing juxtaposition with the room’s geometric rigor. Zeiger analyzed the image, asserting that it expressed an implicit rhetorical strategy, “an ideology of what the space is about.” She contended, “You can’t trust the image to be a document of what’s there.” In part, this is because the image is its own interpretive object, and, in turn, the architectural object is itself a representation of the ideals and ideologies of both its architects and the time in which they worked.

Bestor asked the panelists to consider the ways that architecture becomes a protagonist in a photograph. Baldwin discussed the work of Eugène Atget, who focused less on works of monumental architecture and more on the quotidian, vernacular edifices of early 20th-century Paris. In the image that Baldwin referred to specifically, La Madeleine church literally fades into the background behind a veil of fog while the dingy walls of an ordinary building remain in focus. Anderson discussed working with famed architectural photographer Iwan Baan while curating her exhibition on design responses to climate change-induced sea level rise, currently on view at the Annenberg Space for Photography. She noted the photographer’s fascination with context, exemplified in his use of drones and helicopters to document “the urban condition” rather than just the architectural object.

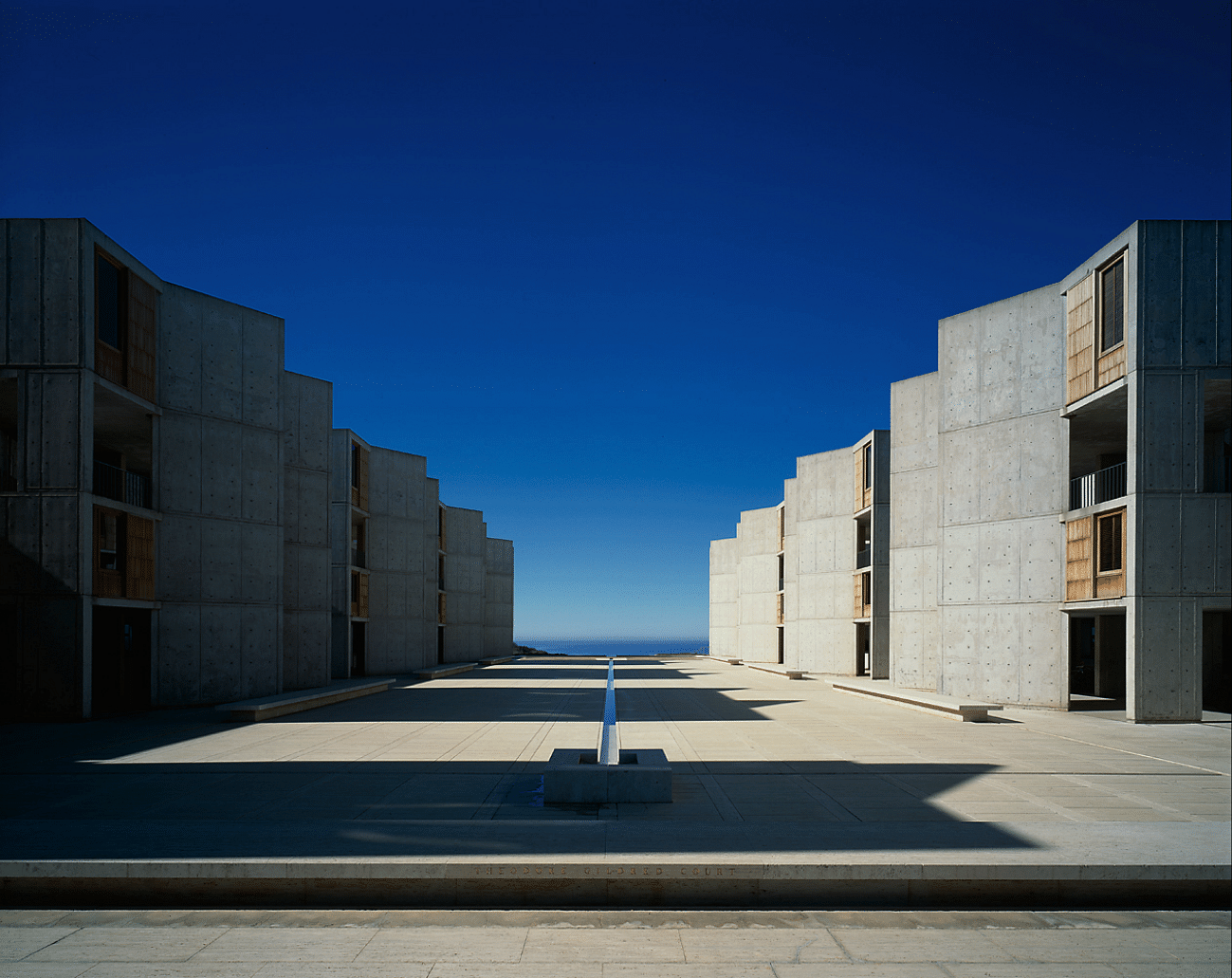

For Welling, it is exactly the broad scope favored by photographers like Baan that he tries to avoid. “What I’m doing isn’t about comprehensiveness,” he stated. Grant seemed to echo the sentiment: “There’s nothing like the real experience of standing in an architectural space,” he said. “Photographs will always fall short when it comes to a great architectural space.” Conversely, Grant noted that some buildings look better in an image then they do in real life. In short, the panelists seemed to agree that the photographer should not aspire to spatial mimesis (which would require the impossible flattening of a three-dimensional place into a two-dimensional image), but rather towards the creation of a unique work in relationship to a work of architecture.

The conversation continued along these lines, touching on the apparent “modernist imperative” for honesty, both in architecture and corresponding photography. Anderton asserted that such an imperative was “fraudulent,” speculating that the flat materiality of late 20th century “PoMo” was actually more honest. Grant asserted, “There’s always been manipulation in photography.” Zeiger seemed to agree, noting that in the photograph of Villa Stein-de-Monzie, an idea of the architecture was infused in the image as an addition to the physical actuality of the place. Focusing closer to home, the panelists considered the particular problems that the morphology of Los Angeles presents to the architectural photographer. They noted how the artist Ed Ruscha and the filmmaker Thom Andersen (“Los Angeles Plays Itself”) both, in their own ways, showed the importance of the moving perspective, either by means of the automobile or the film-camera.

The panel ended with a question about the political implications of photographing architecture. How do decisions about how and what to shoot deal with issues of power? While the panel ended before any satisfying answer was reached, the question helped provoke others that lingered with me as I left the REEF LA building and walked out into the glare of Downtown LA. Can an image adversely affect how we experience a building later in life and in person? How do images prohibitively haunt the possibility of an “authentic” architectural experience? Conversely, how does the continued presupposition of the superiority of the in situ experience support existing power structures? The leap from three to two dimensions inevitably leaves something out: a strange, spectral third object reflecting back the fragility of the bond between place and its representation.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.