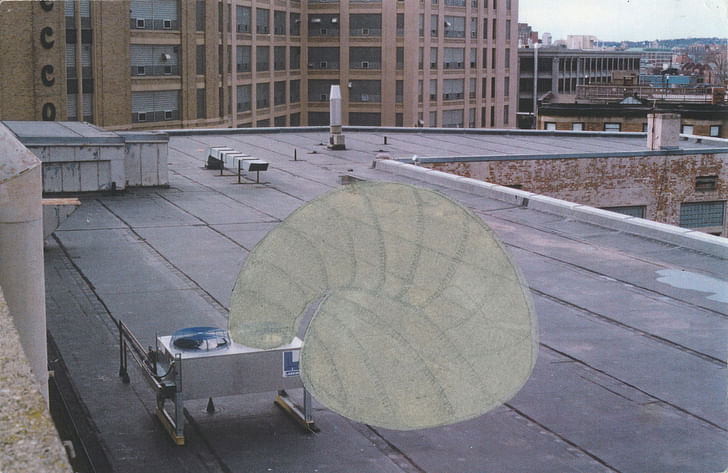

Using the air discharged from publicly accessible HVAC units, artist Michael Rakowitz has created a series of inflatable temporary plastic shelters for the homeless he calls “paraSITE.” The work, which began in 1998 and was later added to the MoMA’s Architecture and Design online collection, is both a form of social protest and an ingenious, budget-conscious design (most units cost around $5 to construct).

Currently a Professor of Art Theory and Practice at Northwestern University, Michael received his Master’s at MIT in Visual Studies, eventually going on to create numerous non-gallery-based conceptual pieces (once, in a food truck) about identity, most often as it relates to the Middle East. He works with a method he has termed “redirective practice,” which allows him to approach other disciplines, such as architecture, as an artist. While “paraSITE” is a relatively early work of his from the late 1990s, his work is currently being exhibited in a show put on by The Graham Foundation entitled “The Flesh is Yours, The Bones Are Ours” running through August of 2016.

I spoke to Michael about the indirect inspiration for paraSITE he received from his family’s history as Iraqi exiles, the design challenges he faced in creating the work, and his intentions for the future.

With paraSITE, you mentioned that one of the design issues you encountered was that the people who were going to live within the structures needed them to be transparent, so that they could see people who might attack them on the street. What other issues did you encounter in this project that either surprised you or that you didn’t anticipate?

One of the things was the issue of storage. In some cases, the way that they talked about the windows was that instead of having a kind of secondary piece of plastic that they would be able to draw in order to achieve a little bit of privacy here and there, the idea was that ziplock bags could be used as a kind of way to address levels of publicity and privacy. There’s one particular prototype that’s documented in photographs, which is basically a grid of ziplock bags. It’s like a reliquary that also allows for the public to see the different objects that are part of a homeless person’s everyday life.

A lot of the folks I started building for in Cambridge and in New York had requested that I don’t do things to address the ground because they have sleeping bags that they use, or they wanted to add their own things to it and adjust it over time. The thing that we found also was that the weight of the person on the shelter itself pushes I was in my studio at MIT where I was a grad student living out this childhood fantasy of sculpting Jabba the Hut out of air and clear plastic fat the air out from underneath it anyway, so it wasn’t possible to inflate the bottom part like an air mattress. They didn’t like the idea of bubble wrap. So, it was like learning like how much to not do. In the case of this one person in New York, he had more or less augmented his shelter to include—you know the vinyl tubing that’s used in a fish tank that attaches to the air compressor and pushes the air through it?—so he got a big piece of that on a surplus store on Canal Street. He was tired of having to get up to go to the bathroom so he poked a hole in the bottom, taped this vinyl tube to it, ran the tube down into the gutter, and so whenever he needed to go to the bathroom he’d just roll over and pee into the tube. It was his way of basically having a bathroom in the shelter.

Those were some of the hacks I really enjoyed hearing about. There continues to be things like that: they add elements to it, or if they need to patch things up, sometimes it’s a different color plastic and it ends up having this very beautiful patchwork appearance. There’s a whole other set of decisions which gets made when they talk about what it is that they desire as opposed to what they need.

LIke what?

It’s like the ability to say, ‘Well, you’ll design anything I want?’ and my response is ‘Well, I’ll do my best.’ And one guy—Freddie Flynn, up in Cambridge—he was a big science fiction fan and he came back with a torn out section of a magazine, and it had a picture of Jabba the Hut. And he said, “I want to live in this.” So for the next 10 days or so I was in my studio at MIT where I was a grad student living out this childhood fantasy of sculpting Jabba the Hut out of air and clear plastic fat. There was another person who had wanted his shelter—it was very beautiful, he was making the distinction between the earth and sky—so the bottom part of his shelter was made from green tarps, and the top part from blue. And it was the beautiful duotone shelter that had the color of green grass on the bottom and blue sky on the top. It ended up looking like this abstract sculpture, like this modernist abstract sculpture, only it didn’t have hard edges, it looked like a pillow. And so those are the things I really find myself falling in love with.

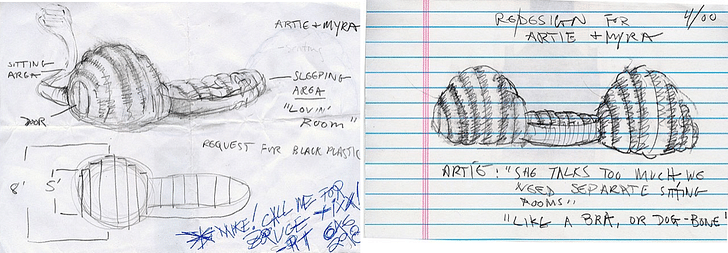

There’s the story about Artie, who at the time was in his 60s, it was like 2000, he was one of those homeless residents around Madison Square Garden. He would get hired to wait online for tickets before people started buying tickets on the internet. He initially approached me for buying tickets for a Springsteen concert. After I told him what I was working on he asked for a shelter for him and his girlfriend, Myra. He wanted a bubble area for him and Myra to sit in and talk to each other and read to each other, and then he wanted this low-lying area that he called “the lovin’ room.” It was like an inflatable sleeping bag. And then midway through it, he said “You’ve gotta stop production, it’s not gonna work. Myra talks way too much so we need two separate sitting areas and a lovin’ room in between, so it will look like a bra or a dog bone.” It was one of the funniest moments. But it was also beautiful, because it was the first and only couple I built for. When we talk about need versus desire, what I insist on is that these are citizens. There’s love, there’s humor, there’s all these other aspects that I was really happy to have incorporated and learn about in the really early stages of this project. It’s not something that avoids the information that inhabits it. What I often talk about is how this project about architecture became about portraiture.

How long would you like to see this project continue? It’s a very playful way of protesting the condition of homelessness and a city’s response to it. Is there a natural ending point or does it extend indefinitely?

I think it extends indefinitely. I feel these things as commitments, as things I’m genuinely interested in. I became very interested in homelessness because of the condition of my own family of being exiles. My mom is from Baghdad, and they had to leave. The thing that sparked this interest was seeing a picture of Palestinian refugee camps. The family that was featured in this photo had reconstructed the facade of the house that they lived in that had been bulldozed by the Israelis. And they had reconstructed it using recycled items, like the detritus of other buildings: pieces of vinyl siding or zinc rooftops, and also plastic bottles. It was a really powerful piece of protest architecture, almost as an apparition of the house that had been.

I was invited to do a residency in Jordan through MIT that was for architects and urban planners. I spent my time there trying to get permission to go to those refugee camps; in 1997 the Jordanian government was very restrictive on who was allowed to go, and who wasn’t. I wasn’t allowed to go but I ended up doing all this research. The camps seemed like this romantic idea of nomadism. I learned that they built their tents each night in response to the way the wind is moving, and I thought that was so beautiful and such a poetic detail. I had no I insist on continuing to make the bandage, because the problem is only getting worse idea what I was going to do with any of that information, and when I returned to the U.S. to Boston that winter I saw a homeless person sleeping underneath a vent, and this was another kind of a wind, and another kind of nomadism: homeless people who are nomadic by consequence, and social refugees and economic refugees. It became a way for me to deal with something on the level of the personal but through something that wasn’t so far away. It was right here, happening as well. One of the things that I appreciate about the activism that’s happening right now is that there’s starting to be a lot of intersections in terms of the way people are speaking about this issue. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Brooklyn or in Bethlehem in the West Bank, dispossession and displacement is something that we can see happening through gentrification and through genocide and other things.

For me, this was a really important moment where I first came to terms with how to work with my own sensibilities, as somebody who is American but has this connection to previous generations that had to leave a place called home. And so I think that, for me, by continuing it, it’s an acknowledgment of the fact that the problems and the projects still exist, but I have to say very simply that I get so much from doing this project. The information that gets transacted—getting to know someone else in the city that’s living in a very different way in the same city that I am. Like you said, it’s a playful thing, but my mentor Krzysztof Wodiczko talks about the bandage as a metaphor for the kind of work that we do. A bandage can simultaneously heal and broadcast. It heals a wound but it also broadcasts something that’s unacceptable. Philosophically, if we’re going to talk about an idealistic perspective on society, people should not have bandages because they should not have wounds. I insist on continuing to make the bandage, because the problem is only getting worse.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.