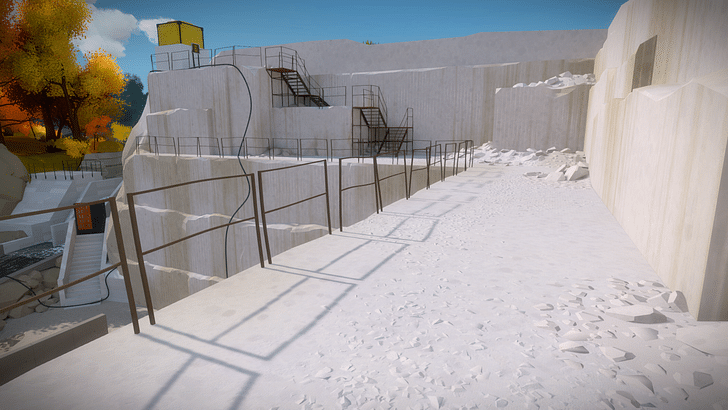

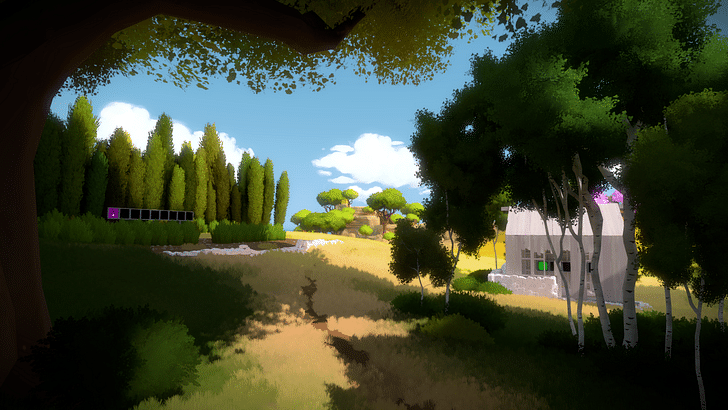

"This is so beautiful – can I live here?” asks user GhostRobo on his YouTube walkthrough of the puzzle game the Witness, verbalizing what many probably feel after first leaving the dark tunnel where the player begins. This a game where the design, built in part by a team of architects and landscape architects, rivals the gameplay.

Released in 2016 to wide acclaim, The Witness is the brainchild of celebrated video game designer Jonathan Blow. The game is intended to not just amuse or challenge, but also prove that video games are an artistic medium in their own right. The game lacks any verbal communication; instead, the player wanders around an abandoned island largely of their own accord, gaining access to more areas by solving increasingly difficult puzzles. There's no clear narrative at work—just the player, the island environment, and the puzzles.Video games are not like real world architecture—there's no constraints

“Video games are not like real world architecture—there's no constraints,” Deanna Van Buren of FOURM design studio and DJ+DS explains over the phone. The lead architect behind The Witness, Van Buren had never worked on a video game before being enlisted to participate in its development. Alongside a team of landscape designers from the LA-and-SF-based Fletcher Studios as well as visual artists, Van Buren crafted the elaborate virtual world of The Witness before returning to traditional architecture.

I spoke with Van Buren over the phone to learn more about designing architecture for the virtual world of a video game.

Were you into games before you started working on The Witness?

No, not really. When I was young I played games. I like to play card games, analog games. But in terms of digital games, I hadn't been playing since I was much younger. So it was something, I think, that was more appealing to Jonathan in some ways. And he's done this with other artists he's worked with—like musicians, he does not work with video game musicians. He hires a musician as a musician. He wanted an architect who was a practicing architect, not a video game artist or someone who was in that industry. I think he feels that that is how you actually start to elevate games to a higher level, an art form, by breaking out of certain ways of thinking.You really have to take time to figure out what everyone's saying and get used to each other

It was a learning experience for all of us, but it was certainly very productive and fruitful and I think similar to a lot of cross-disciple work, which I had been used to doing a lot of, but there's always a time of learning each other's language. You really have to take time to figure out what everyone's saying and get used to each other. Once you do that, and if you can tolerate that time period that it takes, of being uncomfortable and confused, I think that is what helps you get the best and most creative and innovative solutions. I feel that way about the Witness for sure.

How did you initially get involved?

I have my own practice now, DJ+DS, but at the time I had been working for Perkins + Will and doing projects on the side. They were mainly immersive gallery installations. I did one at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, in the room for Big Ideas, and a friend of mine knew Jonathan and had invited him to the installation. So he saw that work and asked her if she thought I might be interested in working on the game.

Through her he contacted me and I had a meeting with him and looked at his game at Perkins + Will. I was pretty sure nobody at Perkins + Will was going to be interested in designing video games and I asked some other firms if they might be interested because I [realized] this is a full time job, and offered to do workshops with him. So we did a few weekend workshops where I created a sketch master plan of the island and looked at tons of image references and tried to develop a language, but I think those were more exciting for me than they were for him because, at the end of that, I don't think he knew what to do with all of that stuff. But what it did was it gave me a sense of what the process could be and that this was very possible. It took me a month or two but I reconsidered my initial ‘no thanks’ and responded with a ‘yes, I'll do this’. And I quit my job and started working on The Witness full time.

How much creative license did you have? Did the game developers come to you with a certain aesthetic in mind or were you given free reign?

I think that the primary person here—Jonathan Blow—is god on this game. He really is the developer and the visionary for the whole thing. He had implied aesthetics in his prototype and we did a pretty robust, intensive series of workshops with him at the beginning to get a sense of where he was coming from. But really we had a lot a creative license. [Blow] allows people who work with him to do their thing. He didn't get in the way, which was fantastic.

We were really responding to the gameplay needs and his concept for the game and there were a lot of implied structures within the narrative of the game, which, if you play, were there from the beginning [...] There were certain things that were in place, but they were just boxes basically.

What were some of the design references that you looked at?

We looked at everything all over the world! This massive file of design references. The way bolts looked during the medieval time and how they got put together. Medieval joinery. Every little bit of the project had to be designed. And the artists weren't architects so they didn't know how things went together. We had to figure that out, [as well as] very contemporary things.

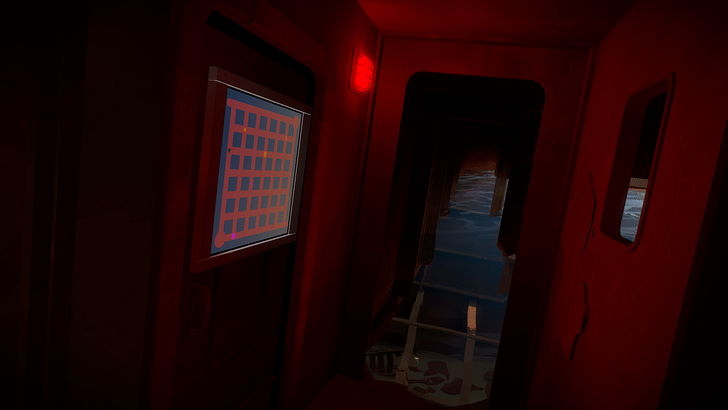

Things like fiction films we were looking at, because, I don't know how many levels you've seen of the game, but there are very disparate [settings]. Everything from abandoned concrete factories to more scientific, space age-y looking things to the tree houses, which are these strange ramshackle [places]. So I had a book on tree houses. I was studying tree houses, I was looking at Hobbit houses.We looked at everything all over the world!

Everything you can imagine we were looking at as references because Jonathan was a tough and wonderful person to work for. He was very demanding and we often would come in with ten ideas for one thing and sometimes he would shoot down all ten, and we'd have to come back with more. Sometimes we would get it right away.

Things were very iterative and very disparate, but there was a fundamental strategy for the architecture in terms of these three civilizations that were intended to be built upon the one before it. But then there were other places that had nothing to do with that, particularly some of the underground spaces.

I'm interested in how designing virtual spaces compares to designing physical ones.

I think when I first started the project, I said well, I don't design video games, I'm a real architect. This is a whole other thing that I don't know. But as we started to work together I realized it's really not that different.

I'd always been a design architect usually. I was always a design lead. So it wasn't like we needed to just get construction documents together or things like that. At the end of the day, [architects] know how to think conceptually so I think just being able to think that way—and not all architects are great at that, but many are—and I think it requires that kind of thinking for sure. If you can think pretty highly, conceptually, then you're just moving into similar processes that you know. We did a lot of sketching. We were doing precedent research. We did a lot of three-dimensional modeling.If you can think pretty highly, conceptually, then you're just moving into similar processes that you know

We did not do a lot of physical modelling, real world models. I don't know, in hindsight, if we should have tried that, but given that the actual end product would never be experienced in real life, it didn't seem as critical. That was the experience of that world, and the dimensions of it, and your kind of vision is different.

Everything that we did, whether we were modelling in Rhino or SketchUp or whatever, we had to bring it into the engine. And the engine is like a Revit model in a lot of way, so even that was not so different. But you would bring things into the game engine and only then could you tell what it really looked like.

So there were slight differences but a lot of things were really similar. We would have regular design meetings every week. We would present the work to them. We'd check it into the model and they'd be able to play the space, in essence, before we got there. It took us a while to realize that was the best process, that we should really be checking things into the game engine that everyone was working in, and once we did that, things were much smoother.

Were there unexpected challenges that arose?

For sure. The biggest challenge was that we didn't understand game play and what game play means, and the psychology of game play and how important it was. It took us a little while to figure that out. Once we did start to understand that it was wonderful because once you understood that these are the constraints of the game, that these parameters that the game designer has put into this, those are the bricks and mortar, or those are the building codes according to which we're going to design.

We were going in like, "Oh we have this concept, look at this great building, isn't it beautiful?" and [Blow] would be like, "So what? It ruins gameplay, now the player can see too far or they're confused, you've confused them, there are too many spaces for them." We had to really step back a lot and think about: does this architecture, do these spaces support the gameplay objectives of this particular puzzle or this particular environment? Once you start to think like game developers, and less like traditional architects—once we got over that hurdle—it was much smoother. [...]

does this architecture, do these spaces support the gameplay objectives of this particular puzzle or this particular environment?

It was weird to get used to the perspective field, it was just a little different. The sun never moves, there's no temporality to it. That was something that's quite different. It's always the same time everyday. It never changes. In our first meeting, one of the first things we asked them was, "Where's north?" And they were like, "Why does that matter?" Also, what angle was the sun at? They're like, "Oh we don't know."

We had to figure out what angle they were using for the sun, or what time of the year it was, and all of that so that we could [design]. It also mattered to game play, where the sunlight was coming through windows, all of that stuff matters so we needed to get that right. So there was a time of just setting all of those things up. In some ways it's easier since nothing's changing but you in the space.

The Witness has such a particular aesthetic. How closely were you working with the landscape designers and other creatives?

The way that video games typically work, in terms of their team, is that you have programmers and coders, and then you have artists who are actually creating the look and feel of the game. They're creating the affect of the game, which are the plants and the leaves and the buildings and the people. But they're also doing the cinematography of the game. So, in a way, they were the contractors, if you're thinking about it in relationship to a real building.

All we could do was design the building, indicate what the materials are, talk about how it was actually built and made and then sit with them. They were the ones who really developed that impressionistic aesthetic and their process is really beautiful. They were looking at different artists and figuring out how to create an aesthetic that didn't have a lot of noise or distraction in it but was still communicating the essence of the thing itself. So they spent a long time working on that and it was really wonderful to see because we, as architects, had a lot of thoughts about ‘well, that doesn't look like wood’, or ‘that doesn't feel like concrete’, or ‘that's not…’[...] These were the people that we as architects worked most closely with. I don't think I ever had many meetings with the programmers, but the art team and ourselves were highly collaborative, and the landscape architects and ourselves were highly collaborative. So we were working together as the art and design team to develop the project.

This feature is part of Archinect's special editorial focus on Games for August 2016. Click here for related pieces.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

5 Comments

Money is in gaming industry.

How does this article not mention MYST at all?!

Seth, if you're into MYST you should check out the new game Obduction. Many are saying it's the spiritual successor to MYST (I believe it's by the same designer as well).

I will get in touch!

I know there is no right way to get into an industry but how can someone position themselves to get into something like this? That would be my question. Great article!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.