When you think of game theory, you might imagine numbers scrawled with a wax pencil on a pane of glass by a troubled genius—calculations extrapolating order out of the apparent chaos of human activity. After all, that’s pretty much how it goes in A Beautiful Mind, the biopic of the mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr., a major contributor to the field. But game theory isn’t just the domain of high-minded academics; it has very real and practical applications, including for architectural design. I talked with the London-based firm Mzo Tarr about their use of game theory in “every aspect of the design process”.

The award-winning Mzo Tarr Architects was founded by architect Adam Tarr after he graduated from the Manchester School of Architecture and the Architectural Association. Game theory, or “the mathematical study of decision-making between people in situations of conflict or cooperation” as Tarr defines it, is integral to their practice. Just about every design project involves a variety of parties—the client, planners, neighbours, investors—whose interests may not necessarily align.Just about every design project involves a variety of parties—the client, planners, neighbours, investors—whose interests may not necessarily align

Game theory helps Mzo Tarr juggle their various demands, quantifying them into ranked priorities known as ‘utility curves’. Game theory even becomes incorporated into the life of their buildings after they’ve been built—for example, facilitating better relationships between neighbours. This isn’t the realm of theoretical or speculative architecture: it’s the primary tool of Mzo Tarr’s professional practice.

I exchanged emails with Tarr to hear more about the basics of game theory and its architectural applications.

How were you first introduced to game theory? When did you realize it had architectural applications?

During my time at the AA, studying under the tutorage of John Bell and Theo Lorenz, I focused on interactive technologies and the potential to create real-time relationships between users and flexible architecture. This led onto a more focused fascination with the decisions people make in response to technology and architecture. After graduation, I continued investigating various methods to better understand the decisions people make and why, and came across Ken Binmore’s writings on game theory. But I would say the real breakthrough in its application came later, during various architectural research projects alongside Dr. Andy Lewis-Pye, professor of algorithmic game theory at the London School of Economics.

Game theory is the mathematical study of decision-making between people in situations of conflict or cooperation. That means any time a decision is made between two or more people, you can use game theory to identify the best strategic decision to make.

Could you give me an example of how game theory was employed in your practice to solve a particularly difficult design challenge?

We were approached to design a concept for a residential tower near Canary Wharf, London for the private rented sector. For Londoners, the priorities when choosing a property are location and space. In this context, space refers first to the size and quality of internal space, and secondly, whether there is garden space. In the course of our research, we also identified that a tenant is more likely to renew their lease if they have a good relationship with at least one neighbour.

Location is, of course, determined by geography and cannot be altered. In contrast, the quality and size of a flat’s internal space can be addressed with good design. This is usually the main focus for architects. However, despite garden space being one of the major factors for tenants, this is often ignored or overlooked by architects when designing towers. We decided that we would give due consideration to the provision of garden space in our design process.Greater collaboration led to better results

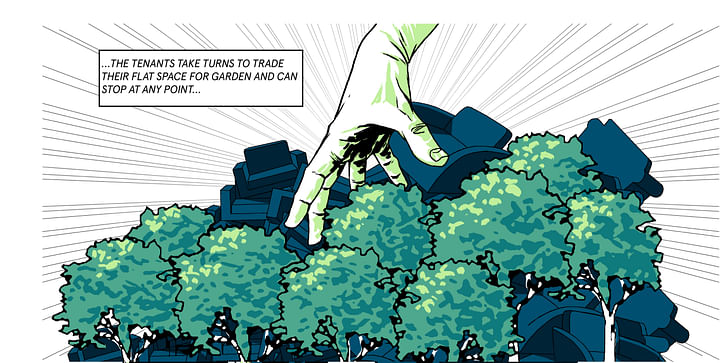

With this information about tenant priorities and behaviour in mind, we used game theory utility curves to create a game that encouraged the flat occupants to create garden space. Each floor of the tower in our design contains five private flats. Located within the centre of each floor is the potential to create a semi-private garden, to be shared by the five flat owners on their floor. This shared space will also encourage community spirit as well as offering a certain level of garden privacy. However, flat occupants have to trade part of their private floor space. The amount they trade is up to them; they can trade as much or as little as they choose but to encourage the flat owners, 2 square meters of communal garden would be created for every 1 square meter of private space given up.

Some flat owners chose to be selfish, giving up no space in the hope they could use the garden created by the other four flat owners’ more selfless decisions. But the largest spaces in terms of private and communal garden space were created on those floors where tenants were unselfish. Greater collaboration led to better results.

What's the relationship between the use of these mathematical models and more intuitive design processes?

People want different things and for any design project to be successful it is fundamental for the architect to accurately understand their client’s motivations. One way you can begin to accurately understand the relationships between the client’s various priorities is by asking the client to rank their requirements for the project. For this reason, we start every project with a quantitative as well as a qualitative design brief.

In order to set up a project as a game, you must understand and quantify the motivations of all the players, not just your ownThese numbers (known as ‘payoffs’) not only shed light on the client’s priorities for the project but also provide the building blocks for how client motivations may relate to those of another party (such as planners).

In order to set up a project as a game, you must understand and quantify the motivations of all the players, not just your own, even if they are educated guesses. Game theory forces you to put yourself in the shoes of others. This may seem obvious but doing it allows you to predict their likely course of action, and you can then decide your own best action in response.

What are the sorts of conflicts you run into in a project that you use game theory to address?

Rarely are two parties’ priorities perfectly aligned. None more so than those of planners and developers. One of our roles as architects is to find some common ground between conflicting parties, whilst negotiating on the remainder. Game theory can help achieve this.

We were recently approached to maximise the value of a site in a conservation area in Essex, just north of London. The client’s brief was unusually clear and contained only two criteria. Achieve a high return on investment whilst simultaneously gaining support from the council, via their pre-application planning process.

Our planning consultant had identified at the start that the client’s requirements would be difficult to meet. This was due to various constraints and planning policies of the conservation area.

We proceeded to build a complex set of algorithms informed by the players’ payoffs and utility curvesAs a result, we decided to spend the next few weeks solely researching the other parties who would impact the council’s decision. We looked into the local community, the planners and councillors. We investigated their jobs, political affiliations, hobbies, the boards they sat on. In this Internet age, this is not that difficult. This built us a picture and enabled us to put ourselves in the shoes of others.

We proceeded to build a complex set of algorithms informed by the players’ payoffs and utility curves. We were then able to quantify in real-time the council’s likely response (in percentages) to basic design changes made to our 3D proposal, ranging from height, style, site coverage, bulk, shadowing, etc. At the same time, we were also able to check the financial impact of these design changes to the potential resale value of the site.

Whilst the client is still deciding whether to progress with the build or sell the site, the council’s pre-application response was favourable, pleasantly surprisingly many, including our own planning consultant. This validated our approach.

Do you find clients appreciate your use of game theory?

Our clients approach us specifically because they see the advantages game theory offers them. From concept, through design, completion and even post occupation, game theory can provide various tools for each stage, to identify issues as well as solutions that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

Game theory cannot predict the future but as construction projects involve many different parties, often with different agendas, game theory is an invaluable way of understanding the principles of decision-making and outcomes. Our clients approach us specifically because they see the advantages game theory offers themMany understand these principles intuitively, but game theory offers a way of communicating it to others who don’t. You can create a game that could involve anyone in any decision-making situation: from planner to client, developer to local community.

According to RIBA, architects are “trained to understand a client’s needs and support strategic decision-making”. I believe game theory and its tools for understanding strategic decision making provide a different perspective for the architect to navigate the complex process of architectural design and construction.

This feature is part of Archinect's special editorial focus on Games for August 2016. Click here for related pieces.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

5 Comments

From theory to practice, this is one of the most interesting ways to shape an architectural project. One could argue that shaping the brief leads to shaping the resulting architectural piece. Even more so when the "tools" you use are the very people who will be living in the space you create. The only element that sets a direction are the set of rules for interaction that you establish at the onset. Dynamic generative design.

Very interesting especially the notion of quantifying priorities to better understand how the decisions of the various parties influence each other.

most excellent. really like game month here on archinect.

Excellent article and very interesting the way Adam is applying game theory in real world scenarios to achieve better outcomes for everyone involved.

I agree with Mzo Tarr’s assertions, to create the best possible design solution it is vital that we understand the site, the demands on the site and the users aspirations and requirements, all whilst meeting financial and timeframe constraints along with the planning department.

It is refreshing to see Mzo Tarr use Game theory for walking that fine tightrope dealing with policy, finance, personal preference, egos, agendas, timeframes, trends and of course the hidden agendas.

As a director of an architectural practice and university lecturer that works nationally and internationally, I see many clients and developments that can benefit from more focused and interactive stakeholder engagement , to create the real-time relationships between users and flexible architecture to enable them to buy into the designs and take ownership of the building.

Mzo Tarr are to be commended for embracing a technology which is enabling them to continually and successfully exceed their clients requirements and aspirations.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.