In 2012, the Network Architecture Lab was invited to participate in the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) “Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities” exhibition, curated by Pedro Gadanho. The exhibition was the third installment in the “Issues in Contemporary Architecture Series,” which included “Rising Currents,” a contemplation on future sea level rise in New York City, and “Foreclosed,” a study of the architectural responses to the foreclosure crisis.

“Uneven Growth” focused on six megacities–Istanbul, Hong Kong, Lagos, Mumbai, New York, and Rio de Janeiro—actively investigating the role of architecture in addressing high degrees of social inequality. The show organized participants into Urban Case Study teams, pairing architects and researchers from each city with a group from abroad.

New York's Network Architecture Lab, directed by Kazys Varnelis, and Hong Kong-based firm MAP Office were tasked with considering a future scenario of Hong Kong in the year 2047. The team began by posing two questions: Can architecture “solve” uneven growth? And what would Tactical Urbanism look like in the future? Rather than seeking a straightforward solution, the group drew from previous research on scenario planning and simulation design to develop an interactive experiment—developing a framework that was reflexive, iterative, agile, and adaptive to changing conditions in real time. Deciding on a tactical approach, Network Architecture Lab set about assembling a special HONG KONG ISSUE of the open-source newspaper New City Reader.

SYMTACTICS was designed as the centerfold of the publication, a physical board game that could be assembled from the newspaper itself. At once a highly designed environment with specific protocols and territories and a corollary to the endless search for understanding in contemporary megacities; SYMTACTICS is also an exercise in tactical design, active play-testing, iteration and diagramming. The result of this process was a chaotic, dystopic simulation of tactical urbanists’ in the year 2047.you are designing a new world—one with its own laws and its own gravity.

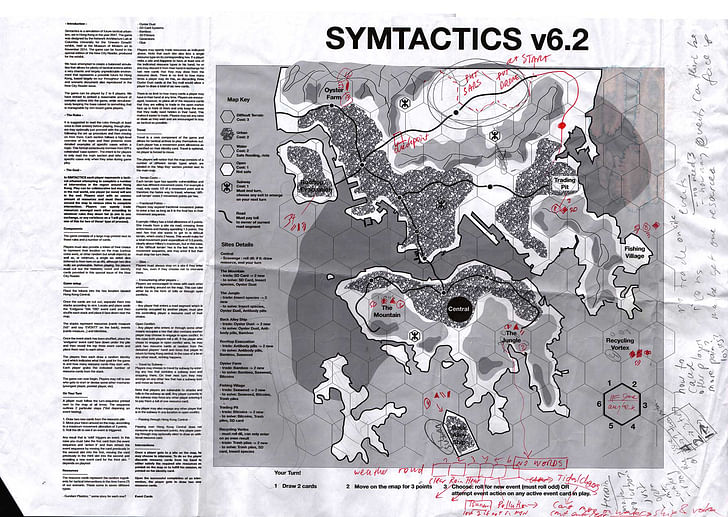

The process of designing a game is necessarily iterative—you are designing a new world—one with its own laws and its own gravity. The iterative nature of game design worked well alongside the improvisational imperatives of the exhibition and its international collaborations.

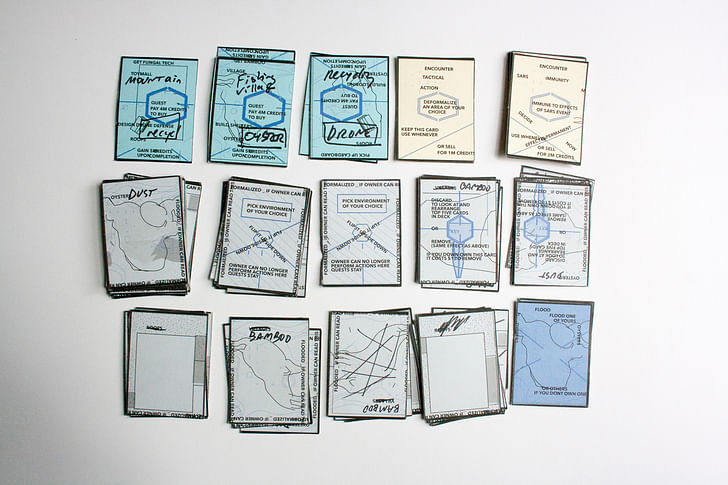

SYMTACTICS took shape after the Network Architecture Lab traveled to Hong Kong to meet MAP office and explore the locations that would become the bedrock of the game. Initially a simple card game, the first edition presented four of the eight sites curated by MAP Office as a series of mazes the players had to escape.

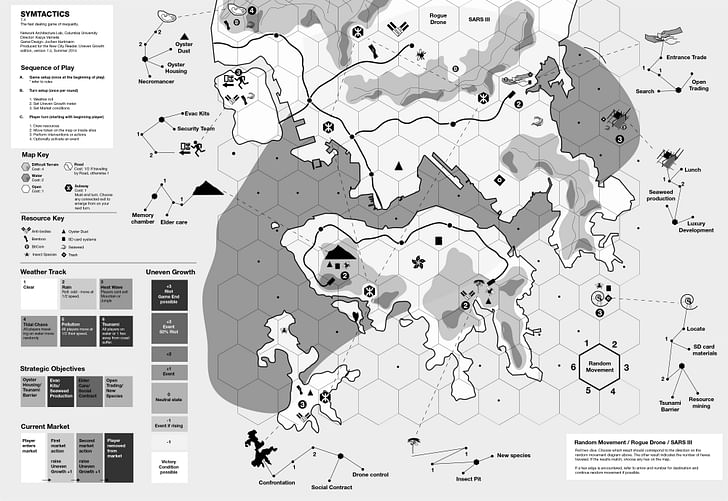

Once back in New York City, the second version of the game emerged with added dimension. Players were now able to perform tactical urbanist interventions at four sites: the rooftops of central Hong Kong, the back alleys of Kowloon, the fish farms near Tai Tau Chao and the oyster farms in Lau Fau Shan. Migrating between physical space and game space, the team developed the future architectural scenarios that we believed citizens of the 2040s might face.

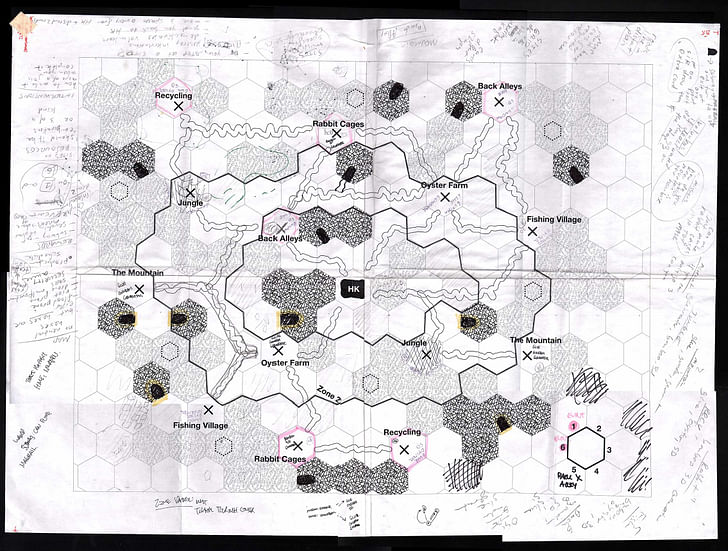

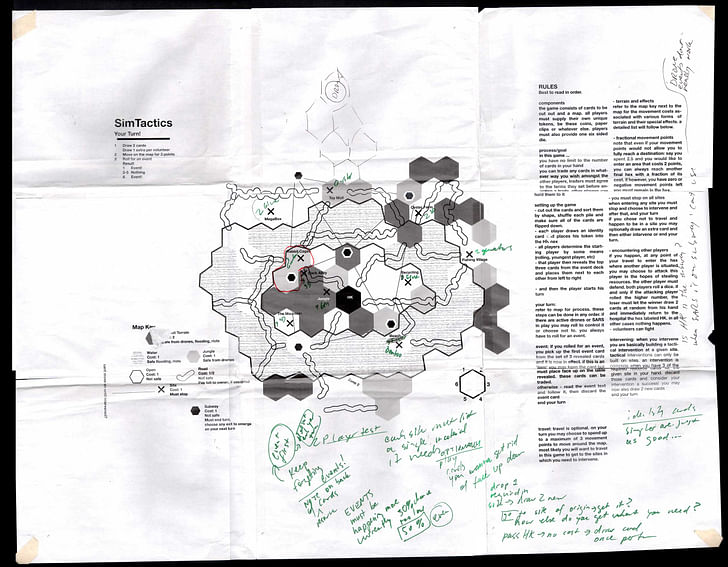

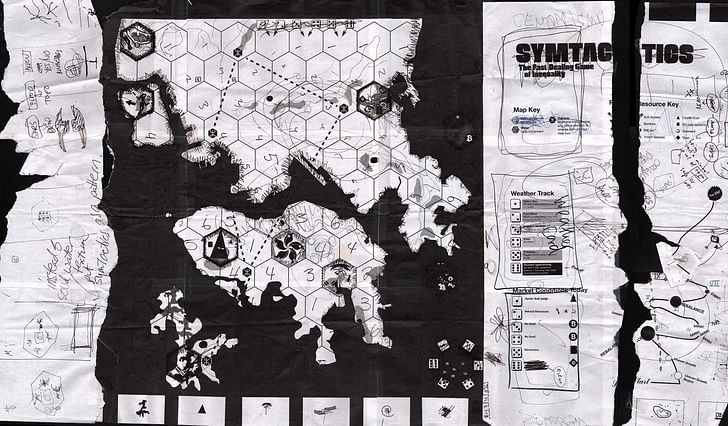

As the game began to display complexities, it necessitated a spatial representation. The third version of the game evolved into a board game that was played on a map. By the fourth iteration, a hexagonal grid, inspired by 1980s war games, was added to allow for maximal unidirectional movement. Despite the game world’s attention shifting dramatically from While traditional war games allow players to alter the outcomes of history, SYMTACTICS’ players must navigate within an unknowable future.physical games to their digital counterparts in the past three decades, SYMTACTICS development was starkly analog—taking shape as cut up scraps of paper and Chinese play money. The early layers of iteration and improvisational thought visible (as drawings, symbols, and scribbles) on the pieces of the game themselves.

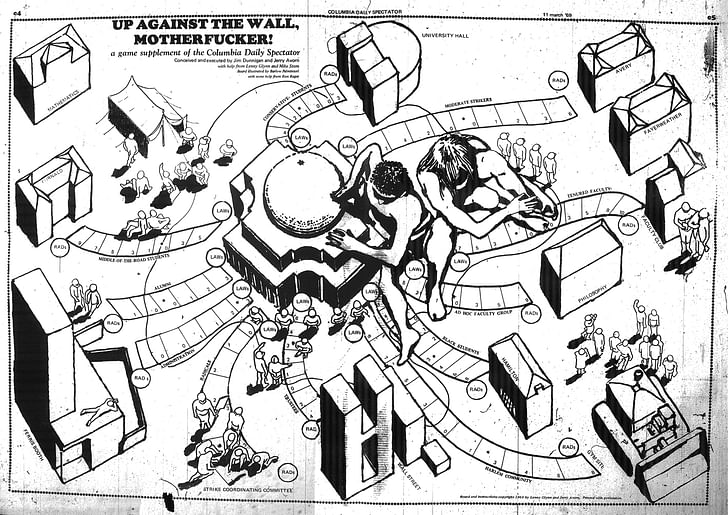

According to Jim Dunnigan, pioneer game designer and theorist, “a war game is a combination of ‘game,’ history, and science. It is a paper time-machine.” Both SYMTACTICS and the war games Dunnigan defines, allow players to simulate moments in time and play out 'what if' scenarios. While traditional war games allow players to alter the outcomes of history, SYMTACTICS’ players must navigate within an unknowable future.

Dunnigan describes game design as an exercise in “mushware.” A former missile technician and one of the most prolific war game designers in the history of the genre, Dunnigan published “Up against the Wall, Motherfucker” in the Columbia Spectator while a history student at Columbia University. The board game simulation of the 1968 campus protests pits students against the police. Mushware, a term coined by Dunnigan in the 1990s, refers to the processes that run in the human brain rather than, say, in the inaccessible recesses of a computer. He conceived the term to separate physical war games from their digital counterparts. Unlike mushware, digital games bury the complex logic of the game inside algorithmic black boxes. Given that SYMTACTICS began as an experiment to better understand tactical urbanism, all processes needed to be in plain view. The analog approach exposed the hidden logic behind the scenes–the simulation–and provided the necessary conditions for an iterative, open-source version of development.

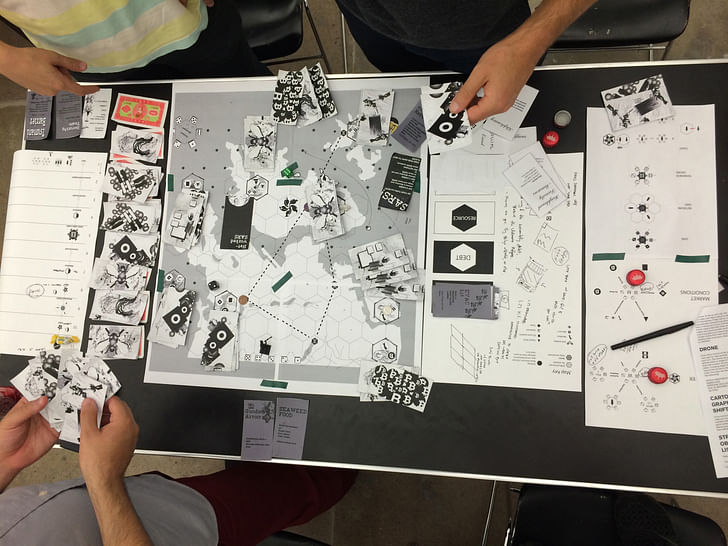

Once SYMTACTICS became a map, it was continually UX tested, redesigned, and refined. This endless process allowed the team to test myriad mechanics and degrees of complexity. Sites like a trading pit, trash vortex, and evacuation island—all developed during the Network Architecture Lab and MAP Office's exploration of Hong Kong—were added to allow players to earn resources and build interventions that prevent catastrophes. In the game, performing interventions temper the architectural and environmental disasters that contribute to increased amounts of 'uneven growth'. A controlled amount of chaos was added to the game through random events that players must read about in mini-newspapers at the start of each turn. These cataclysmic events include complex weather conditions, SARS outbreaks and various other technological disasters that players must overcome through teamwork.

During a workshop organized by MoMA at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna, an “uneven growth meter” was added to the game to represent the constant and growing threat that players would need to combat together—inserting the premise of the exhibition into the very objective of the game along with a stock market and weather meter.

Game design allows not only for interactions in design but for experiential iterations that result in a more dynamic and collaborative game play. One of the most important rules in game design is to create something “fun.” Though an accurate hedonometer is hard to come by, this became our ultimate test, the driving telos of the project. How could we tackle the weighty brief while creating a simple and intuitive game? This was the ultimate challenge—as a game without engaged players is not really a game at all.How could we tackle the weighty brief while creating a simple and intuitive game? This was the ultimate challenge

The most recent version of SYMTACTICS (version 12), printed in an edition of 30,000 for the exhibition addresses the question of "fun" by leveraging an asymmetrical game system informed partly by betting and the inherent tensions in collective enterprises. In the final edition, players can either work together to solve uneven growth, seeking 'collective victory' by periodically rebalancing the system and surrendering their individual resources or they can personally amass as many resources as possible in attempt to win big on their own.

The primary takeaway from the development of SYMTACTICS is that game design has the potential to become an unparalleled tool for scenario planning. While the traditional method of researching historical precedents in an attempt to predict the future is valuable, it remains relatively static. Game design, on the other hand, creates a space where we can ‘activate’ scenarios and play through what the reality of those scenarios might be. By engaging these situations through gameplay and experimentation, we open the door for new insights into what the future may hold.

Jochen Hartmann is a multi-media designer and software engineer. He is currently the project lead for The Synapse, a permanent installation that explores the intersections between neuroscience, data visualization and journalism. His background combines both architectural design, software ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.