"[The] sovereign art, of course, will be the one whose laws rule over the relations among men in their totality. That is, Politics.

Nothing is alien to Politics, because nothing is alien to the superior art that rules the relations among men.

Medicine, war, architecture, etc. – minor and major arts, all without exception – are subject to, and make up, that sovereign art." — Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed, 1973

There is perhaps no more satisfying aspect of architectural and urban design than the ability to envision and communicate visions that change the built environment. To do this we have a set of go-to tools: plans, sections, models, renderings, etc. Many of our tools, however, are famously not so good at expanding the conversation, allowing non-architects to join and even question and rework proposed visions. This becomes even more difficult when wanting to engage a broader set of stakeholders who may not understand architectural conventions. This is why I have become increasingly interested in how games a system with loose rules for others to interpret and execute as they see fit and gaming can supplement other design tools to broaden the socio-spatial imagination and conversation. The potential that games bring to architectural production is an open-endedness that seeks to not simply validate a preconceived idea, but instead tests it and creates opportunities for change.

My interest with games began with a fascination early in architectural school with Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings. For these drawings, Lewitt created detailed lists of instructions and diagrams for how to produce the art piece, allowing others to execute them as they saw fit. The results of these drawings can range widely and carry with them the subjectivities of those who carry out the instructions. I saw in this a potential way of creating new kinds of architectural and urban projects—setting up a system with loose rules for others to interpret and execute as they see fit and as the conditions on the ground allow for.

Although LeWitt’s systems are flexible enough to allow for interpretation or even multiple subjectivities to co-inhabit the same art piece, I was curious to see how these systems can become sites to experience political processes. That is, how can a loose framework allow people to not only interpret rules, but also negotiate them with other players and make the very negotiations that created the piece visible?Among the goals of this theater activity is to tease out conflicts related to power and oppression

While researching this political potential for games and gaming, in January of 2013 I attended a performance by the group Theatre of the Oppressed NYC at Housing Works. What I saw that evening was a form of Forum theatre in which a group plays a scene they have rehearsed and then those in attendance are invited to come and replay the scene differently. As a methodology, Theatre of the Oppressed does not believe in a separation between actors and spectators, rather theorizing that everyone in attendance is a Spect-actor. These moments of reenacting serve two main functions: to test out different outcomes for the scene that challenge dominant power structures, and to introduce a multitude of personal experiences and subjectivities that may not normally be part of the dialogue or public consciousness.

After each time the scene is played a joker, or facilitator, leads a discussion and reflection on how the scene was changed and what that may mean. Among the goals of this theater activity is to tease out conflicts related to power and oppression—the performance at Housing Works explored the challenges of disclosing HIV status and interactions with police for the LGBTQ community of color—to understand how they affect differentgames provide a way of negotiating space, testing policy impacts, linking personal experiences to a systemic structure, and producing spatial ideas. populations and to enact potential ways to overcome those challenges. Often replaying “solutions” leads to an understanding that systems of oppression are complex and often internalized, and that no solution is easy to enact in practice. In short, this is a performance methodology that provides a way to role-play ways to create political change on any given issue, allowing those affected by the issue to bring in their experience and ideas.

Now, this methodology is not meant to be a silver bullet, but rather one that shows just how difficult and interrelated power relations and social change can be, and allows for strategic planning as well as the creation of communities interested in helping move change forward.

Theatre of the Oppressed holds clues for architects and urbanists who want to engage broader audiences, as its process provides a platform to discuss deeply embedded conflicts and to role-play current conditions and potential futures. Furthermore, it provides clues as to how design, and the designer, can act more as a facilitator than as a creator of final products.

My interests in games, inspired both by artists and performers, has led to collaborations, commissions and courses over the last few years that test out these ideas. I will talk briefly about five projects in which I have observed games playing a role in the production of architectural and urban space. Three of these examples are located in the Jackson Heights and North Corona neighborhoods of Queens, one is a performance about architectural labor issues, and one is a housing project with an open-ended master plan. In these projects, games provide a way of negotiating space, testing policy impacts, linking personal experiences to a systemic structure, and producing spatial ideas.

GAMING SPATIAL NEGOTIATION

A Shared Plaza: A Game of Negotiation in Common Space

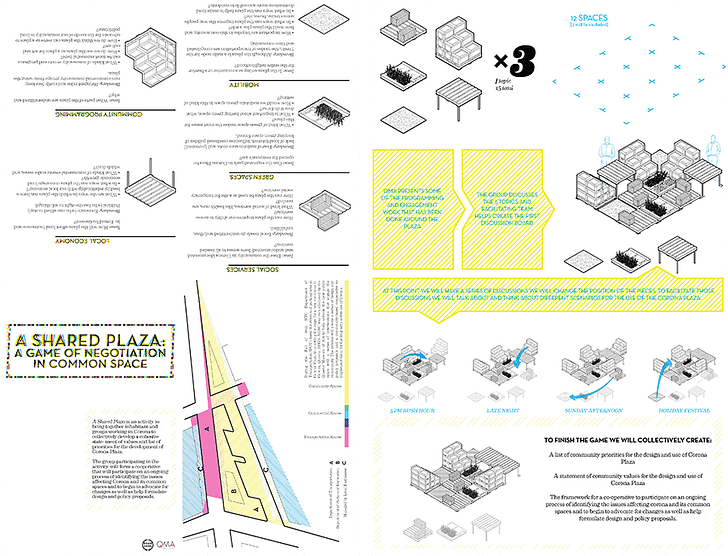

In February 2013, my practice, DSGN AGNC, was commissioned by the Queens Museum to work on community engagement designs for the proposed Corona Plaza, a new public space in an immigrant neighborhood of Queens. One of the projects we produced is “A Shared Plaza,” a large-scale game designed to bring together residents and organizations in North Corona, Queens to collectively develop a cohesive statement of values and list of priorities for Corona Plaza’s development.

The game consisted of 15 40-by-48-inch game pieces, three pieces for each of the five topics we identified through previous conversations with the community, which included community programming, economic opportunities and other social services needed in the area. The pieces represented functions related to each topic. For example, the Community Programming pieces contained a set of bleachers and the Local Economies pieces symbolized tables to set up around the plaza. Finally, the “playing field” consisted of tape on the ground that allowed only twelve pieces to be placed within a three-by-four grid, imposing the practical reality of limits on space and resources in the process and setting the conditions for negotiation.

Playing the game, participants moved the pieces around as we gave prompts for discussion, and discussed the future of the plaza—including its most contentious issues. We talked about the very different experiences men and women have in the space, about policing and how stop-and-frisk indiscriminately targets young men from the neighborhood, and about fears of gentrification and the lack of entry-level economic opportunities for existing residents.

Although we were playing the game on a cold and snowy day, the game and resulting conversation lasted for several hours. In the end no final “designs” were made for the plaza. Instead we talked about the type of actions required to continue this conversation on social and spatial issues. The game also led to overall design recommendations to create a flexible open plaza with opportunities for communal conversations. I am still working on research and engagement projects in Corona that will be compiled into what I am calling an urban action plan. As the research moves forward, it will continue to be based on a conversation with local residents. (1)

GAMING POLICY EFFECTS

Agenda Engine!

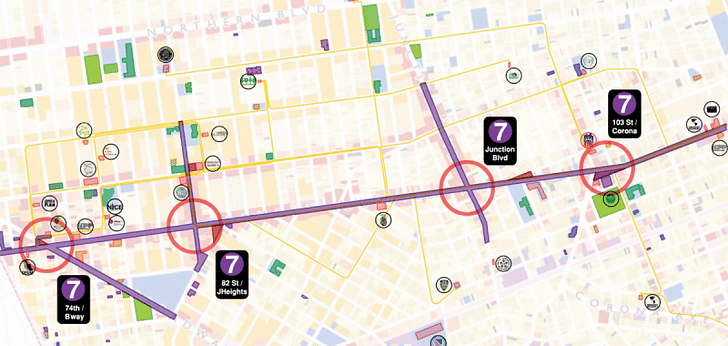

My interest in North Corona went beyond Corona Plaza itself when news reports announced that the maintenance partner was leaving the project and a Business Improvement District (BID) of over twenty city blocks in length was proposed to help maintain and administer the plaza. A BID is a structure by which land and/or business owners in an area choose to pay a new tax which funds physical and other improvements to the district, based on decisions made by a private BID administration structure, with boards that can include some of those same land/business owners. Although BIDs have often improved a business district’s identity, cleanliness, and sense of security, some What often ends up happening is that the players who began with most political clout points begin to slowly accumulate more and have a bigger sayscholars and organizations question the amount of private control over public assets that a BID may lead to. Furthermore, the BID proposed for Jackson Heights and North Corona faces fierce opposition by some small business owners, tenants and even property owners in the corridor out of fear that the BID will force mass displacement of small immigrant business owners.

In the Fall 2014 semester I organized a graduate studio for the Design and Urban Ecologies program at Parsons School of Design at The New School to explore this issue. The students were tasked with studying the history and structure of BID’s as well as the local patterns of immigrant entrepreneurship and use of urban spaces. For their final projects, students worked in teams to come up with a variety of proposals that included mapping oral histories, a new network of spaces open to the public in North Corona and finally, aggregate-designed public space areas on every block’s sidewalk, to create the potential for a new structure for taking care of public spaces.

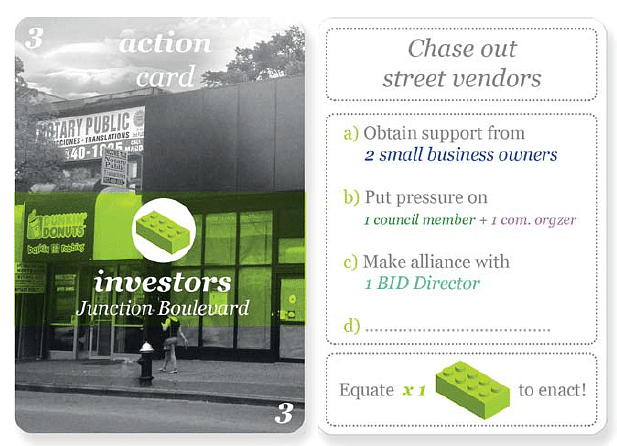

As their final project in the studio, a group of students comprised of Kartik Amarnath, Mateo Fernández-Muro, Demetra Kourri and Masoom Moitra developed a game that would help people in the area learn about the processes of creating a BID and would facilitate the creation of alternative collaboration structures. The game they created asks each player to take on the roles of the people and groups who run or are affected by a BID. These groups include local council members, the BID director, small business owners, street vendors and community groups. Each player begins with political clout pieces related to their assigned roles that they can negotiate with, which vary based on the power relationships they have relative to the other players who are part of the BID process. What often ends up happening is that the players who began with most political clout points begin to slowly accumulate more and have a bigger say on the policies and structures built in the corridor.

The game could then be played a second time with a new set of negotiated rules and political clout points that could lead to different configurations. For example, groups representing street vendors making alliances that can help maintain and administer public spaces as the BID would do. The game got a lot of attention locally and even by national press (2), and was played multiple times in English and Spanish in Jackson Heights and North Corona by different community groups and in meeting spaces.

GAMING FROM THE PERSONAL TO THE SYSTEMATIC

The Architecture Lobby

Just last fall, The Architecture Lobby, a collective organization I am a part of, put together a performance event very much influenced by Theatre of the Oppressed. In this case, a large group of collaborators developed and performed ten scenes, one for each point in The Architecture Lobby’s manifesto on labor rights of architects. Spect-actors were then asked to come up and replay the scene as per the processes of Forum theatre.Or, to put it another way, can a game itself be the design?

During the performances, we experienced how the somewhat generic scripts were re-performed to include rich personal anecdotes about the conflicts embedded in studying architecture, working at an established firm and running your own architectural practice. Anecdotes included experiences of internships with low to no pay, working hard for clients that either do not pay or low-ball fees because they think they can always find someone willing to work for less, and making hard choices about life-work balance. As a group we discussed and unpacked those narratives as each person came up to try to insert a different narrative or outcome rather than the expected, dominant one, and discussed ways in which we can make changes to labor conditions that many architects are unhappy with.

GAMING SPATIAL PRODUCTION

Finally, I have been increasingly been interested in how games can help in the design of new spaces. Or, to put it another way, can a game itself be the design?

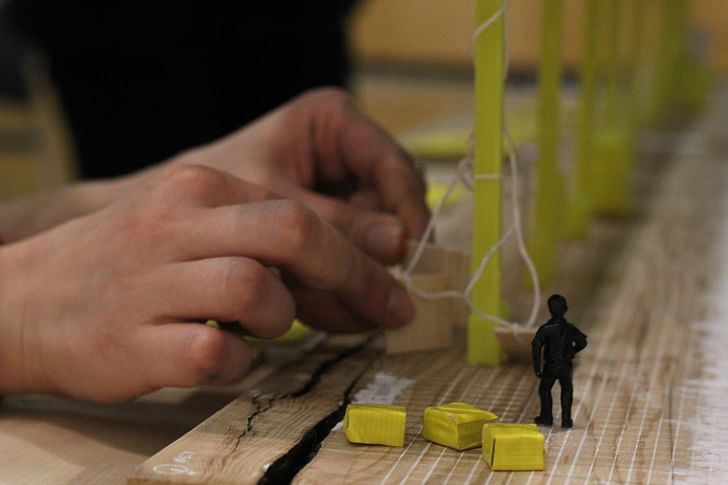

For this category, two projects come to mind. First, a few years ago in a collaboration with Estudio Teddy Cruz and landscape architect Simon Bussiere, DSGN AGNC designed a housing project in Granada, Nicaragua (3). The design of the master plan was complicated by one major issue: a lack of reliable information about the site. It was known that topographic conditions and the location of trees were key to the design, yet such information was difficult to obtain. This was seen as an opportunity to challenge the hard-lined master plan that sometimes dictates even the most minute details of a spatial community. The master plan started out with one goal in mind: to save as many trees as possible while creating safe and flexible housing clusters that housed all existing residents. To reach this goal, a set of simple directions were given to create a flexible urban armature, within which each house could be sited according to conditions on the ground. These instructions were simple and could be applied by anyone building the houses (local inhabitants, volunteers, or a professional construction crew) without much training.

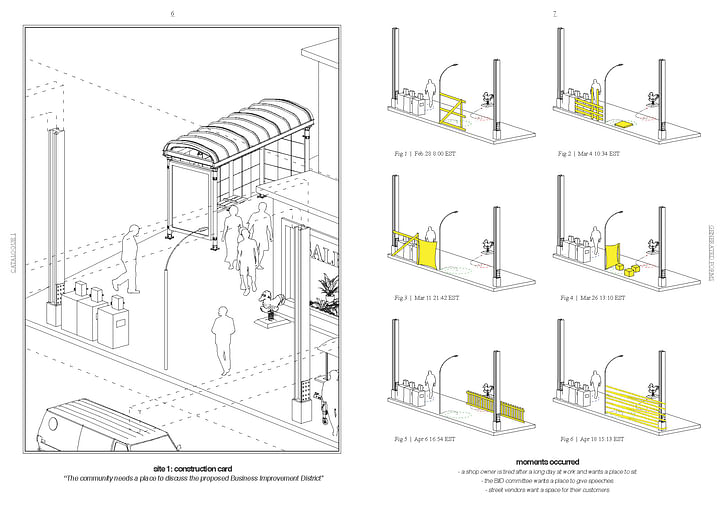

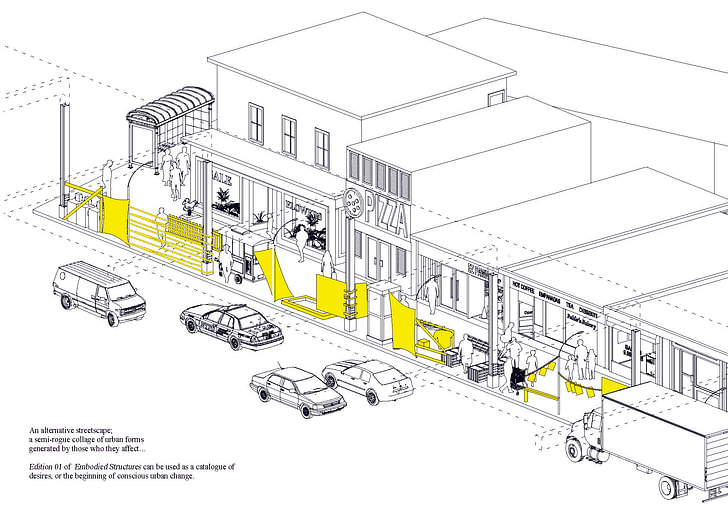

For another example of a game tackling spatial production, we can return to North Corona, Queens. This was the site I chose again for a Masters of Architecture studio at Carleton University. I asked this studio to research the everyday patterns of public space use in North Corona and Jackson Heights and to use their research and observations to design new public spaces, that were better sited and worked to potentially rethink existing political dynamics, including those of the BID. A team comprised of students Matina Cavayas and Matt Hagen studied the area where Roosevelt Avenue meets Junction Boulevard. They decided to work on a game to give the nearby school and other community organizations an increased role in the production of temporary urban spaces. The game takes advantage of areas in the elevated 7 train structure as sidewalks and left-over spaces created by the meeting of two urban grids on Roosevelt Avenue.

The students created a system in which new spatial needs would be identified and then enacted. The game allowed for full spatial production of temporary spaces and pointed participants to the NYC departments they should coordinate with, how to raise funds and which local resident groups and institutions might be able to help. This game combined accessibility of design, made with children in mind, with real information about local political and social realities that could help create designs needed by the community—and for those designs to change as the needs of local residents changed.

Each of these projects shows how the application of games in architectural practice and education can open up new ways of producing and questioning design processes. Instead of presenting finalized visions, games provided an opportunity for engagements with broader publics, and avenues for these participants to imagine different configurations and management systems for public spaces—whether at a policy, social or physical level.critical games can create the conditions for ongoing negotiations and shaping of space

The examples from North Corona and Jackson Heights show how this works: the Shared Plaza game created a conversation about the future of Corona Plaza by giving participants visual clues of what was discussed. In the Jackson Heights Agenda Engine! game, students were able to create a tool that allowed people on the ground to question policies that affect urban management from the vantage point of all the disparate players. Finally, Embodied Structures from the Carleton University studio goes meta with the architectural process, allowing people to create and judge small-scale spatial constructions along Roosevelt Avenue. The potential is that a process of creating these structures would help civil society—in this case headed by the local school—gain agency in the change of urban spaces.

It is perhaps in this last point, which proposes that critical games can create the conditions for ongoing negotiations and shaping of space, that games may be able to have their biggest impact in design. In order to shape space, we need to be able to negotiate space and the flexibility to envision change. When treated as a game that does not necessarily assign winners and losers, the negotiations can be rehearsed and the changes can be piloted. This transforms designers into facilitators, guiding more robust processes that accommodate the diverse publics that are the primary users and potential beneficiaries of the spaces and urban conditions we help design.

This feature is part of Archinect's special editorial focus on Games for August 2016. Click here for related pieces.

Notes:

(1) For More Information see the Queens Museum’s Corona Plaza Es Para Todos Making a Dignified Public Space for Immigrants, 2016 and WHICH PUBLIC? Article in the ARPA Journal.

(2) Press for final projects of Roosevelt Avenue studio at Next City and Brian Lehrer’s TV Show.

(3) For more information on this housing project in Granada, Nicaragua see DSGN AGNC’s website.

Pratt Institute DeanDSGN AGNC founder Quilian (pronounced: Killian) is the Dean of Pratt Institute’s School of Architecture, working across the school’s architecture, landscape, urban design, planning, and management programs. Quilian also serves as the Vice President for Architecture ...

2 Comments

Quilian is basically doing what I was working on in Grad school back in 2007 - the gameification of architecture - the approach I took had to do with design process and urban integration

xenakis, that is stochastic!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.