“Should our homes have an airplane mode?” asks the Italian architecture studio Space Caviar, in the descriptive text for their RAM House, a fully-equipped smart home that alternatively doubles as a refuge from the ubiquitous technology of today.

As our domestic spaces become increasingly crowded with smart devices that monitor, track, and upload our behavior as data, notions of privacy must be revised and, likewise, new architectural strategies must be invented. Walls and curtains only block one part of the “electromagnetic fog” surrounding the home of today, Space Caviar notes.

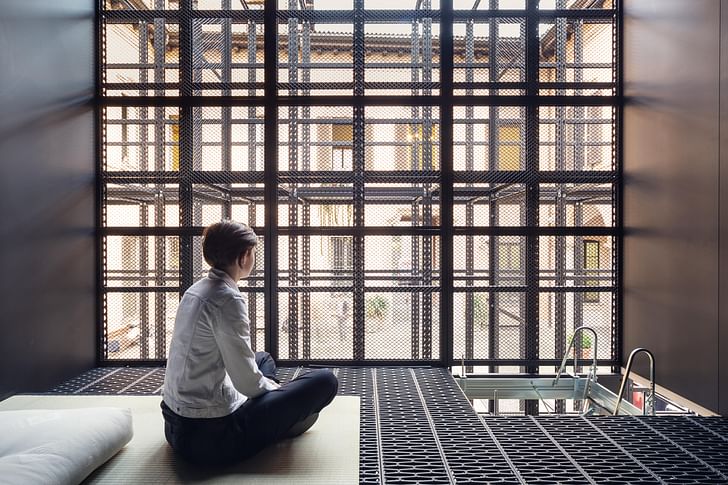

Built last year in the courtyard of Palazzo Clerici in Milan, the RAM House was equipped with the latest in high-tech smart devices—kitchens, bathrooms, and libraries that sense and respond. At the same time, the prototype house also had sliding cabinetry that would block electromagnetic signals, as well as radio-absorbent material (RAM) and Faraday cage mesh. The user could determine whether the curtains were drawn against virtual gazes, so to speak, or opened up.

I chatted with Joseph Grima, the founder of Space Caviar (alongside Tamar Shafrir) as well as the co-curator of last year's Chicago Architecture Biennial and the former editor of Domus, to hear about the ideas behind RAM House and discuss what privacy means today, more broadly.

Who is Space Caviar, when was it founded, and does it have any sort of a mission statement or guiding ethos?

Joseph Grima: Space Caviar is an architecture and research office based in Genoa, Italy. It was founded by myself and Tamar Shafrir in early 2013 but a lot of the projects were rolling already, pre-existent in some ways. [...] It's very much an ongoing project in which one research leads into another and so it was really set up in order to give a structure to a set of pre-existent ideas, concerns, and interests, and to try and formalize those into a research and design practice. [...]

[Our work] tends to be quite experimental in nature, not so much driven by architectural preoccupations of a conventional nature. We really try to systematically explore the outer fringes of architectural thinking—trying, wherever possible, to bring it back into design and We really try to systematically explore the outer fringes of architectural thinkingpractice through a variety of means. Or I guess, more than design practice, specifically, more in the sort of some form of output or another.

Sometimes this leads to projects that are more architectural, such as RAM House and others that are less architectural and perhaps more filmic, like [the] 99 Dominos [project] that we produced for the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2014. The outcome is often somewhere between installations and productions of prototypes or film, something that's been a recurring theme.

It kind of all revolves around...a relatively specific set of interests and preoccupations, one of which is the question of privacy, specifically, and the question of the relationship between domestic space and technology, more broadly speaking. I guess even more broadly speaking—and this is something I've been very interested in and that's driven my work I guess all the way from architecture school—[we have] an interest in the space of domesticity, the domestic space, and the sort of way it becomes an incredible opportunity for key insights into our culture.

The way that we live is often an incredible mirror for who we are and so, in that sense, looking at domestic architecture—which has often been overlooked, or at least marginalized except from a kind of theoretical end of the spectrum—I'm much more interested in. The way that we live is often an incredible mirror for who we areAs a practice, we are much more interested in domestic space in real life and to look at it as a way of gaining insight into culture and society. [...]

Domestic space is one of the most contested spaces; it's a space that's extremely fraught with political and social issues. I think there's been moments in history where architecture has really overlooked those questions and that's something that we really wanted to bring back to the forefront, and to problematize again, and think about how we as designers should be dealing with the opportunities and challenges that come with the question of living.

Speaking to one of these domestic prototypes, the RAM House project is described as a domestic prototype that responds to a new definition of privacy. Can you sketch out the context that this project responds to? How does the ‘electromagnetic fog hovering over the city,’ as you write in an accompanying essay, alter traditional paradigms of surveillance and privacy?

Sure. In fact, I guess there were a couple of interesting points of departure for thinking about this project [...] One of them was the observation of an increasingly invasive, or rather unsubtle attitude, towards the notion of privacy within domestic space on the part of technology companies. The kind of blasé attitude on the part of Silicon Valley toward the notion of the home, where the home was just something to be optimized. It's really a throwback to, I guess, a sort of Jacques Tati[-esque situation] but in a less visible form: the idea that one could simply enter domestic space and optimize the shit out of it in every possible way without any sort of critical attitude towards this or any understanding of what the implications of this were.

We thought that was quite interesting to see that there was, on the part of the whole technology industry, a kind of complete lack of what 'home' represents to many people, which, on the other hand, was also overlooked by many simply on the basis that they didn't understand what they were installing in the home.the smart home can be something that we can coexist with and that we have control over There are a number of projects that came out of that on the part of artists, coders, developers, and so on, that really sought to draw attention to that.

One of them was this—you probably came across it at some point—this Russian teenager or something who put together a website that collected all of the live feeds from nanny cams around the world whose owners hadn't changed the passwords. So it was completely all of this information that was being streamed out of peoples homes just out there online, broadly, completely open and accessible to everyone.

Then a number of other also slightly more theoretical interests or inspirations such as...a brilliant essay by Robin Evans, who was an architectural historian from London [and] who wrote a brilliant text on the wall and the notion of the wall as something that in architecture has been, throughout history, essentially an element capable of giving shape to one's own very specific idea of the world, what the world is. Sort of the idea of a wall as a filter, I guess, through which one filters out everything that one considers undesirable about one's environment. This very beautiful essay kind of redefines the wall—this pile of bricks, one on top of the other—as something that's capable of editing reality. And [it] became a very interesting point of departure for us for thinking about how one could actually rethink the wall. [...]

There's a slightly humorous side to [the RAM House], in which the whole notion of the Faraday Cage is thrown out there … as if anyone would actually want to live inside a cage, and of course that's not the point we're trying to make. If anything, [the project is] also slightly critical of a Luddite attitude towards technology in which the only escape from it is to completely block it out.

What we were actually much more interested in was—and the RAM House is actually a smart home—an attempt to redefine the notion of the smart home, to make the smart home into something that's not a binary choice between a dumb home and a smart home but to think how the smart home can be something that we can coexist with and that we have control over, as opposed to being something simply that we're victims of. So in that sense, it was really an attempt to regain agency over the technology that we live together with, and to also think about how this could be an architectural opportunity for thinking about the wall as something that's not simply a filter for the visible spectrum of light, which simply stops passers-by from looking into our bedroom window. thinking about the wall as an editing device, something that allows us to switch on or off reality depending on our moodsBut actually thinking about the wall as an editing device, something that allows us to switch on or off reality depending on our moods, on the time of day, on who we're with, on what we're doing. And, in that sense, the wall is not simply something that is a barrier, that no one can see through, but it's something that's actually a device or a tool to connect, that can be turned on or off. [...]

That led us to rethink architectural space in the sense of how a home could be—the whole idea of the tag line that we gave to the RAM House is this idea of "the home with an airplane mode," where it could be either active or inactive depending on one's choice, a little bit like how there's times with one's phone when you don't want it to be active and there's times you don't want your house to be active. But, at the same time, there are times when you do want it to be active, you want it to be on.

So a lot of the idea behind the RAM House is that it actually would be incredibly smart. It would be populated by every possible kind of automator and would really take advantage of the incredible technologies being developed but without the practice of that being to entirely give up one's agency over it.

Technically speaking, how was this achieved?

The idea was basically that the RAM house is divided into two levels: there's the upper level, which is more of a room, so to speak—you might have seen some of the photos. It's clearly a more intimate space. And then there's a lower level. [...] Both spaces are characterized by a certain indeterminacy and the idea is: it's not like there's a bedroom and a kitchen in a conventional sense of the home, but [rather] thinking about how different spaces have different functions at different times of the day.

We worked with a company that produces these storage systems that operate on track and that can be cranked open or shut. The lower level is occupied, in part, [by] an open space and there's also, within these cabinets that are on tracks, a number of...different functions that can be selectively exposed. One is a kitchen unit that can be opened when one wants to cook, another is bathroom/shower unit, another is a library unit, another is an office unit. looking at the idea of the wall and the barriers and boundaries on a broader spectrum than simply those of visible lightBasically one can crank open any given function at any moment and essentially transform the possibility of how one can use this very very small, very limited space downstairs. Or one can close the whole thing and then essentially it becomes like one big metal box: nothing can escape from [it] and nothing can enter. So that's effectively 'shut-down mode.'

The same is true for the upper level, a space that can be completely exposed to the exterior. It was always a space that was intended to have a specific view in front of it that would respond architecturally to frame the landscape, but that could, while on the one hand be completely open, could also be, electromagnetically speaking, the curtains could be drawn so that one is effectively alone. Or one could, vice versa, be connected but could pull the blinds so that no visible light could enter and nobody could see through. So it's kind of looking at the idea of the wall and the barriers and boundaries on a broader spectrum than simply those of visible light, so to speak.

At the same time that we’re seeing these emerging smart home technologies, we’re also seeing dramatic revisions of the form of domesticity—what constitutes the family unit, blurring delineations between public and private, labor and leisure spaces. Was this paradigm part of the thinking behind this project?

Yes, it is and actually the following chapter of the project has engaged even more with that aspect, which hasn't taken yet so much a physical form but it began with a speculative text that we wrote for Volume Magazine's issue Shelter. The premise of the piece is very simple: it's essentially a very short piece of science fiction in which the story revolves around this episode of a woman being fired by her house. What we were trying to explore was the idea that one of the fundamental transformations that have occurred around the infiltration of technology into domestic spaces—but also in terms of the activities that take place, the deterministic nature that architectural space has had for a very very very long time—in which, more or less, there was a pretty clean division between spaces of labor, spaces of repose, relaxation or rest, and spaces of circulation or whatever else. one of the fundamental transformations that smart phones brought about is the ubiquity of laborThat's probably [one] of the most significant transformations that's taken place in the history of architecture.

This text, in turn, was inspired by this report we were reading by IKEA. IKEA did a very interesting series of reports on the state of domesticity in different cities around the world. It was divided into three parts: one on the morning, one on lunch, and one on the evening—something like that. And they did a ton of interviews and polls and data collection in twelve different cities around the world.

There was one fascinating page in this report that went something like: they asked a bunch of people in London how many people who had full time jobs—who had a job and went to work—how many of them had worked before they went to work. So from home before they went to the office. And the answer was, I think, 43% said they had. Or they did regularly. And then, in turn, they asked them, "Where did you do that?" From your bed? From the living room? From the bathroom? It turned out that 12% of people regularly worked from the bathroom before going to work. So that was kind of like this completely absurd scenario that probably even just twenty years ago wouldn't be—if you had told people that in [twenty] years from now, 12% of Londoners will work from the bathroom before going to work, that would just bend your mind out of shape. What on earth does that mean? Because the reality is that that's one of the fundamental transformations that smart phones brought about is the ubiquity of labor.

We were interested in thinking about the architectural consequences of the home as a space of labor, which of course, [this is something] that already Airbnb has introduced: a culture of micro-entrepreneurialism into the home that's become extremely widespread. But, of course, it's going beyond that.

the home is becoming a factory of data to the point that one could pay one's rent through the process of producing data simply through a set of domestic activitiesPart of the thing that we're looking at is...this notion of data being new oil, something that can be mined, that can be collected, and that has an inherent value; thinking about how the home is becoming a factory of data to the point that one could pay one's rent through the process of producing data simply through a set of domestic activities. A little bit along the lines of the logic of Facebook, which provides you an incredibly valuable service on the basis that you pay for it, essentially, by using it. That's the kind of...weird logic that we've become completely accustomed to.

So [we’ve been] thinking about habitation, dwelling, as an activity, as something that's akin to using Facebook, that you [could potentially] pay for simply by doing it [...] But, of course, labor is something that you can be assigned or that can be taken away...you can be fired from. That became an interesting thought-exercise in thinking about how this notion of the home as a factory of data could then actually transform the space.

I think that's something we're going to be working on more in the coming year. We're still in the early stages.

Are new decentralizing technologies like the blockchain, for example, part of your thinking with this?

Yeah it is. The blockchain is a very specific technology and it's got a lot of, almost too much press in a way, over the last couple of years. But the principles behind it—regardless of whether its blockchain, specifically, or anything else—I think decentralization is very much something that underpins a lot of our project. We didn't really take it head-on in the initial chapter of the RAM research. But it's actually [part of] what, ideally, we're looking into for probably sometime next year or maybe in the next twelve months. We're hoping to actually try to relocate the RAM House to somewhere permanently as sort of an experiment in completely off-the-grid living… Sort of off-the-grid, but also massively on-the-grid. Smart home in the middle of the desert, sort of idea.

It's a pretty complicated thing for all sorts of reasons but definitely working on it.

Around the time he was curating Fundamentals, Rem Koolhaas talked about the smart home and said, essentially, that for the first time we have these elements of architecture that our duplicitous, that aren't saying what they are. He also described the smart home as 'potentially sinister'. Do you agree with that conclusion?

I think that's a little bit of a misunderstanding. I don't think it’s the elements that hide themselves that are sinister, I think it's the agency behind them—and [only] in certain instances. I don't think you can discount them wholesale because the agencies and the intentionalities and the politics behind them are so divergent that it's like saying that all auto manufacturers are bad because of Volkswagen's pollution scandal.

The particular way they work is not inherently evil. It's what done with them, the potential of the way they work. And often, unfortunately, and partly because we're so early on in this new era, I think there's also a lot of very cavalier attitudes towards the extraordinary power of these devices, for sure. [the smart home] disrupts the order of things that architects have become familiar with and have come to rely on to assert their own preeminenceBut I don't think it's the usual question of, “Is it the device itself that's evil or dangerous?” or, “Is it the framework that it's been set into that's problematic?”

And I think this is not something that's going to go away. These things are definitely here to stay and, in fact, this is the very beginning. I think Rem's attitude towards this is interesting because it essentially represents a cry of fear that I think has spread through the architectural profession as a whole. I think, in part, because of a lack of understanding of exactly what all of this is, and also partly because, I think to some extent, it disrupts the order of things that architects have become familiar with and have come to rely on to assert their own preeminence.

I think it's an incredibly interesting move because this preeminence yet again—and it's not, by any means, the first time in the last fifty years that it's been shaken up—but I think this is possibly the most interesting and most profound reshaping of architectural space that's happened to date. I think that one of Bjarke [Ingel]'s weapons in his march towards global domination of BIG has been an attitude of openness and embrace towards this [..] I think an attitude of conservatives fear-mongering…really rings of a conception of architecture of a different era. So I think it is something that we're definitely going to have to get used to and that we're going to have to be extremely proactive about if we want to have any say in the shape of future architectural landscape, because there's also a very high probability that we could be just kicked out and marginalized. [It’s] a little bit like the way we were by pretending the developer didn't exist in the late 70s and look where we are now.

This interview is part of Archinect's special thematic focus for June, Privacy. Do you have projects that grapple with changing notions of privacy today? Submit to our open call by Sunday, June 19th.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.