From chaste bunking to on-site Pilates classes, co-living companies have as many versions as a cover band. But each incarnation raises the question: how do we architecturally define privacy in the 21st century?

PodShare founder Elvina Beck, standing next to one of the 18 curtain-less, bunk-bed-style pods that occupies the outfit’s 2,000 square foot downtown location, looks displeased when I say I’ve been speaking with other co-living organizations. “They are not really co-living,” she says, before going on to explain that within PodShare everything is a shared enterprise by design, and other outfits tend to be more “corporate.” Elvina’s branding strategy saunters past the notions of dorm rooms and hostels into a fully-fledged lifestyle: sexless, drug-free, self-policed communalism for adults that is designed to encourage "collisions", a term referring to unexpected social interactions.

Indeed, during my tour I collide with a number of so-called Podestrians: a still sleepy 26-year old tourist from China named Winter, a 22-year old writer mixing up breakfast in the shared kitchen named Aimee, a thirty-ish couple from Australia named Olivia and Dylan who are bunking in one of the Elvina's branding strategy saunters past the notions of dorm rooms and hostels into a fully-fledged lifestylefew double-sized beds for several days before continuing on their eight-month trek to Central and South America. Most of them have been here only a few days, although Aimee is thinking of extending her stay through the summer. All of them tell similar stories about arriving in Los Angeles knowing no one, but after checking into PodShare being able to immediately grab a meal with a fellow Podestrian. Sited on an edge of L.A.’s gentrifying Arts District, PodShare is close to a Metro stop and features a low-slung view of downtown’s ever-multiplying towers, a vista that is perhaps as awe-inspiring as it would be alienating to someone without any connections in the city.

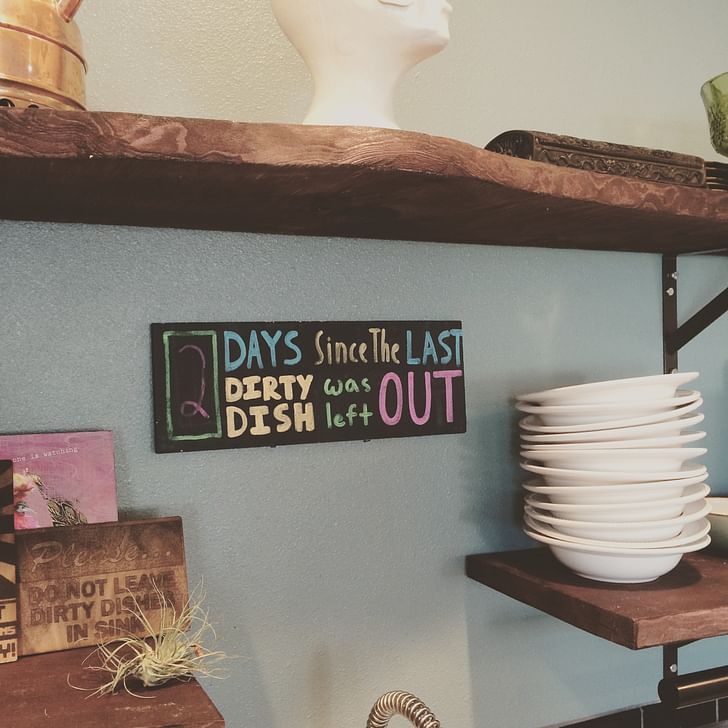

For this reason PodShare, which features hand-fashioned design elements including an airplane wing as a table (“it references travel” Elvina says) seems to be the DIY cradle of sweet-natured nomadism. Each set of bunks has a strip of blackboard on which residents write their names in chalk, using arrows to indicate who is inhabiting which bunk. Every pod comes with its own wall-mounted viewing monitor and a fresh towel. Laundry services are provided by a set of rotating volunteers who often trade the cost of a stay for washing duties, a role Elvina compares to that of an RA in college. Aside from a curtain in the shower, doors on the bathroom stalls, and a rack of personal lockers, the near-zero privacy creates an inescapable intimacy which would be intolerable if not for PodShare’s ebullient, youthful vibe. People here are too busy leading their unfolding lives to become outright voyeurs. At least, that seems to be the unspoken agreement.

If PodShare could be said to embody an extreme openness, it’s worth noting that privacy itself has become a gradated term, especially as it applies to housing arrangements. In a housing economy that is increasingly as much about the disparity between the rich and the poor as it is people here are too busy leading their unfolding lives to become outright voyeurs. about blurring the divide between public and private life, housed privacy has become both more expensive and, to some, less desirable. It’s less desirable among those people who work so many hours that they have little time to grow their social networks, while for people who grew up in an era where freelancing and short term contracts are a backbone of commerce, owning their own home or even renting their own apartment in pricey urban centers has become something they’ll either do in a few decades, or never at all. And why would they want to sink all that cash they don’t have anyway into something that isolates them from what’s actually going on?

At PodShare, where a night’s stay ranges from $40 to $50 (with a separate $15 daily creative lab fee), co-living serves the dream of flexibly accessing the sophistication and opportunities of urbanity without the financial hassle. But other co-living ventures, which aren’t nearly as spartan or cheap as PodShare, are selling the equivalent of a more affluent, built-in community. Companies like WeLive and OpenDoor offer more opportunities for privacy at adult-like prices: each resident can have his or her own room and bathroom, for example.

At WeLive, private studios start at $2,550 a month in their New York City location, and $1,640 a month in Washington, D.C. The monthly flat amenities fee (which includes utilities, internet and a monthly cleaning service) runs $125. WeLive also makes use of seemingly undesirable or awkward real-estate: they transformed a 27-story Hurricane Sandy damaged office building in lower Manhattan into their first co-living residence, a 200-unit cluster of floor-linked “neighborhoods.”

“We felt like Lower Manhattan was a really interesting neighborhood,” Miguel McKelvey, Co-Founder and Chief Creative Officer at WeWork explained to me over the phone. WeLive, which started in tandem with WeWork, was always an integrated part of the now well-known Each neighborhood's slightly different design elements and finishes are meant to create a sense of belonging co-working venture, but took a little longer to launch precisely because real estate in the size and configurability they need is hard to come by. In the case of the Manhattan building, both WeLive and the building’s original landlords took a calculated risk: according to McKelvey, the resulting transformation has made the site look like an obvious choice in retrospect, but it was a blend of both vision and luck. “Lower Manhattan is a neighborhood in transition. It’s obviously historically been the home of finance in New York, and it’s transforming to be a much more mixed-use neighborhood. We felt like we could contribute to that, and that energy of change and evolution is a cool thing to be a part of.”

In addition to their New York location, WeLive currently is operating another building just outside of Washington D.C., in Crystal City. Similar to Lower Manhattan, Crystal City is a neighborhood in transition: formerly the lifeless digs of a series of defense contractors and satellite federal offices, it is now becoming a livable, even thriving place. This transformation is largely owed to the revamping efforts of realty trust Vornado, which took over a large portion of the area’s real estate before turning it over to new residential and commercial tenants.

McKelvey, who trained as an architect, designed a multi-floor grouping of “neighborhoods” within the two WeLive buildings that would foster a sense of community while still layering in degrees of ownership and privacy. In his scheme, each neighborhood consists of three floors with a similar finish and design that are connected via an open stair. The idea is to try and maintain a group of about 20 to 50 people in order to be able to stage events like fitness It might be hard to know everyone in the building, but you could know everyone in your neighborhood.classes or pop-up dinners by chefs. Different common areas are located on different floors, encouraging people within the neighborhood to move from, say, the shared kitchen to the laundry room, and randomly encounter other residents. Each neighborhood’s slightly different design elements and finishes are meant to create a sense of belonging within a particular space, while simultaneously differentiating those spaces from other parts of the building. “If everything was abstracted, you wouldn’t know what the delineation was between your space and somebody else’s space,” McKelvey said.

Also, McKelvey noted that the spatial concept encourages the formation of a larger building identity while still preserving that essential sense of belonging. “You could have competitions amongst neighborhoods. Or you could have this neighborhood host another neighborhood for a little weekend get-together. Or you could have a birthday party where you invite people from your neighborhood. An important part of that allows you to understand a smaller number of people. It might be hard to know everyone in the building, but you could know everyone in your neighborhood.”

Meanwhile, the West Coast-based organization OpenDoor, founded by Jay Standish and Ben Provan, is currently operating on a much smaller scale, with three renovated houses in San Francisco’s Bay Area. Much like WeLive, OpenDoor buys properties that fall within that rare Venn diagram of availability and adaptability: in this case, relatively affordable houses that offer a high number of single rooms and large, convertible open spaces. A one-night stay at one of their properties costs roughly $90 depending on the room and the house, and one-year leases for private rooms are comparable, if slightly below, market rates for similarly-sized apartments, according to Standish. The scale of their houses allows OpenDoor to create not “neighborhoods” but idiosyncratic communities of perhaps 12 to 20 people in a process that Standish, when I spoke to him over the phone, likened to raising a child.

“We think of ourselves as facilitators and enablers that create the conditions for an authentic and unique community to unfold,” he said. “We don’t dictate the culture, but we nurture it to come into being, similar to child-rearing, if you will. The kid is its own being. We’re not in the business of controlling how people interact.” However, he allows, “there is a lot you can do to invite and sort of create the opportunity, the space, for that to unfold.”

OpenDoor curates its members by inviting applicants to think about their intentions and what sort of goals they would have as a community, outside of simply living together and sharing space. The idea is to fit new members into the existing community. To aid in this, there are one year leases andWe don’t dictate the culture, but we nurture it to come into being, similar to child-rearing temporary stays available for the vetted curious. In broad strokes, OpenDoor’s three current houses have distinctly different cultures: one is centered around food and local agriculture with plentiful acoustic music nights, another has more of an artist/maker/workshop vibe, while the third Standish describes as “social entrepreneurs, people who are interested in using their work in the world to make a positive impact and thinking about their role as a leader, and their personal development.”

This notion of creating specific goal-oriented cultures, especially in the case of the social entrepreneurs, purposefully permeates the boundary between work and life. Standish compares the house to a kind of genuinely relaxed long-term mixer, where similarly motivated people can develop organic bonds over time, as opposed to trying to connect over watery cocktails in a track-lit hotel ballroom. “‘What do you want to achieve in life and how can this house be a support structure in that?’” Standish asks of his potential applicants. “And then they kind of fill in the blanks.”

Much as WeLive has purposefully designed its space to create a sense of identity, OpenDoor has put considered effort into creating communal spaces: particularly, the kitchen. “We design it around the kitchen. And we have a shared food program to support that as a core of really living together and eating together—it’s what brings a community into being. One of the buildings we bought we actually completely gutted and reformatted it, and moved the kitchen around and opened it up and tore down walls. Now there’s a big open plan kitchen that flows into the dining and living space. It’s all just one big room, because that’s really ideal.” PodShare is both quiet and alive, thrumming with that mixture of hope and uncertainty that is perhaps the definition of youth.

Along with the attention to common spaces, Standish tells me that OpenDoor residences also take care to include quiet, more introverted spaces in their design. “We have little nooks and dens in some of the houses. There’s an upstairs, smaller, more intimate common space that’s like less of the hubbub of a community dinner or of people socializing in the evenings. It’s a place you might go to read a book by yourself, or have tea with two other people. If people are having dinner, or you’re just feeling introverted, or you have social hang time planned with just two people, you can go into the upper living room.”

I think of this need for introversion as I climb the stairs to PodShare’s upper balcony, where a lone iMac with a screensaver reading “counterintelligence” silently keeps watch over the plywood pods below. Before its current incarnation, this 2,000 square foot space was occupied by a single man. A washer and dryer hulk in the converted adjacent storeroom; a basil plant, nurtured by a grow light, hangs out on the airplane wing table. PodShare is both quiet and alive, thrumming with that mixture of hope and uncertainty that is perhaps the definition of youth

As Elvina escorts me outside, I ask her how she managed to fund and launch this operation, which began in 2012. After borrowing $15,000 from a person she was living with (a sum she tells me she paid back within three months) she rented her first space and began building the wooden pods with her business partner and PodShare COO, Kera Package. Since then, thanks in part to crowdfunding, the operation has grown to three locations in Los Angeles, and Elvina would welcome an expansion across the U.S.

She tells me a story about how her father, an American hailing from a generation when the idea of owning one’s private home practically underlay the national identity, was initially skeptical about the idea of adults wanting to live in such close and non-private quarters. After visiting PodShare, however, he became one of her most enthusiastic advocates.

“The future is access, not ownership,” Elvina says, restating PodShare’s motto before hugging me goodbye. I wonder if she’s right.

This feature is part of our special June editorial theme of Privacy. More on the shifting boundaries around private space can be found here.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

5 Comments

.....currates members......future is access......i actually find this alarming.

this looks like a migrant detention center for hipsters.

It's all sunshine and singalongs until somebody has a few too many IPAs and crawls into the wrong pod.

Imagine the smell

Seems like they also curate on skin colour in those places...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.